W HEN I STEPPED INTO the hospital room, Gerhard laughed. He said something. Weird, throaty words came out of his mouth. Then he laughed again. I cant remember my grandfather ever being so pleased to see me. The doctor told me the stroke had damaged the language centre in Gerhards brain. All he could do now was express emotions. The rational side of him was blocked. I reflected that it had been precisely the other way around before.

Gerhard talked away at me. I pretended I understood. Eventually I told him that unfortunately I didnt understand anything at all. Gerhard nodded sadly. Perhaps hed hoped I might be able to free him from his speechlessness. Just as Id sometimes helped him out of his emotional stiffness in the past. With a joke or a cheeky remark that shook his authority. I was the clown of the family, the one nobody suspected of evil intentions. I could overstep the mark with the hero of the family, the man no one else dared to contradict.

A clear spring light shone through the window of the hospital room. Gerhards face was slack and empty. We said nothing. I would have liked to have a conversation with him. I mean a real conversation. Usually conversations with Gerhard turned into monologues about his latest successes after ten minutes at the most. He talked about books he happened to be writing, about lectures hed given, about newspaper articles people had written about him. A few times I tried to learn more about him. More than the stories everybody knew. But he didnt want to. Perhaps he was scared of getting too close to himself. That hed got used to being a monument.

It was too late now. This man, for whom language had always been the most important thing, has become speechless. I cant ask him questions any more. No one can. Hes going to keep his secrets.

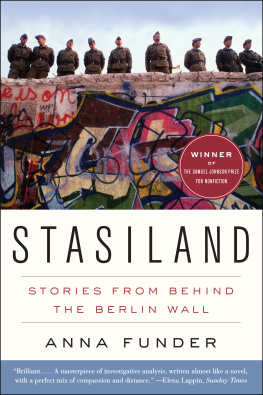

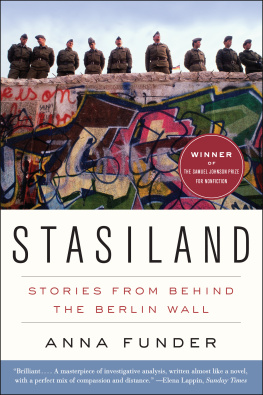

Gerhard was a hero even before he entered adulthood. At the age of seventeen hed fought with the French Resistance, was tortured by the SS and freed by partisans. After the war he came back to Germany as a victor and built up the GDR, that state in which everything was to be better. He became an important journalist, a part of the new power. They needed people like him at the time. People who had done everything right in the war, people you could refer to if you wanted to explain why this anti-fascist state had to exist. They sent him to schools and universities. Again and again he talked about his fight against Hitler, about torture, about victory.

I grew up with those stories. I was proud to belong to this family, to this grandfather. I knew Gerhard had had a pistol at some point, and that he knew how to use explosives. When I visited my grandparents in Friedrichshagen, there was apple cake and fruit salad. Again and again I asked Gerhard to talk about the past. Gerhard talked about frightening Nazis and courageous partisans. Sometimes he jumped up and acted out a play with different parts. When Gerhard played a Nazi, he pulled his face into a grimace and spoke in a deep, gurgling voice. After the performance he would usually give me a bar of Milka chocolate. Even today I think of those monster Nazis every time I eat Milka chocolate.

In the presence of adults, Gerhard wasnt as funny. He didnt like anyone in the family to go around politicking, as he put it. In fact everybody who didnt, like Gerhard, believe in the GDR, was politicking around the place in one way or another. The worst was Wolf, my father, who wasnt even a member of the Party, but had married Gerhards favourite daughter Anne, my mother. There were lots of arguments, mostly about things I only really understood later on. About the state, about society, about the cause, whatever it happened to be. Our family was like a miniature GDR. It was here that the struggles took place, the ones that couldnt be fought out anywhere else. Here ideology collided with life. That struggle raged for whole years. It was the reason my father went around the house shouting, why my mother secretly cried in the kitchen, why Gerhard became a stranger to me.

Gerhard and I sat together for a while on that spring day in that hospital room, which smelt of canteen food and disinfectant. It was slowly getting dark outside. Gerhard had caved in on himself. His body was there, but he seemed to be somewhere else. It may sound strange, but I had the feeling that the GDR only really came to an end at that moment. Eighteen years after the fall of the Wall the stern hero had disappeared. Before me there sat a helpless, lovable man. A grandfather. When I left we hugged, which I dont think wed ever done before. I walked down the long hospital corridor and felt at once sad and elated.

That day I wished for the first time that I could go back to the GDR. To understand what had actually happened there. To my grandfather, to my parents, to me. What had driven us apart? What was so important that it had turned us into strangers, even today?

The GDR has been dead for ages, but its still quite alive in my family. Like a ghost that cant find peace. Eventually, when it was all over, nothing more was said about those old struggles. Perhaps we hoped things would sort themselves out, that the new age would heal the old wounds.

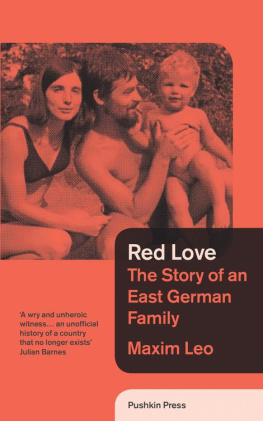

But it wouldnt leave me be. I went to archives, I rummaged in cupboards and boxes, I found old photographs and letters, a long-forgotten diary, secret files. I asked my family questions, one after the other, for days, weeks. I asked questions that Id normally never have dared go near. I was allowed to do that, because I was a genealogist now. And all of a sudden our little GDR was there again, as if it had been waiting to emerge again, to show off from every angle, correct a few things and perhaps lose some of the rage and grief that were still there.

On that journey into the past I became reacquainted with Gerhard, Anne and Wolf. And I discovered Werner, my other grandfather, whom Id barely known until then. I think something was set in motion after that day with Gerhard in the hospital. A speechless man made us speak.

I M THE BOURGEOIS IN OUR FAMILY . Thats chiefly because my parents were never bourgeois. When I was ten, my father walked round with his hair alternately dyed green or blue, and a leather jacket hed painted himself. He barked when he saw little children or beautiful women in the street. My mother liked to wear a Soviet pilots cap and a coat that my father had sprayed with black ink. They both always looked as if theyd just stepped off the stage of some theatre or other, and were only paying a brief visit to real life. My mates thought my parents were great, and thought I was a lucky person. But I thought they were embarrassing, and just wished that one day they could be as normal as all the other parents I knew. Ideally like Svens parents. Sven was my best friend. His father was bald with a little pot belly, Sven was allowed to call him Papa and wash the car with him at the weekend. My father wasnt called Papa, he was called Wolf. I was to call my mother Anne, even though her name was really Annette. Our car, a grey Trabant, was washed only rarely, because Wolf thought there was no point washing a grey car. And hed painted black and yellow circles on the wings so that you could see us coming from a long way off. Some people thought the car belonged to a blind person.

Svens parents had a colour television, a three-piece suite and cupboards along the wall. In our house there were only bookshelves and a seating area that Wolf had cobbled together from some pieces of baroque bedroom furniture. It was quite hard on the bottom, because Wolf said you didnt need to be comfortable if you had something to say. Once I drew a plan of our flat the way Id have liked to have it. A flat with a three-piece suite, a colour television and cupboards along the wall. Wolf laughed at me when he saw it, because the policemans family that had lived there before had furnished it exactly as it was on my plan. He told me it was stupid and sometimes even dangerous always to do what everybody did, because it meant that you yourself didnt have to live at all. I dont know if I understood what he meant at the time.