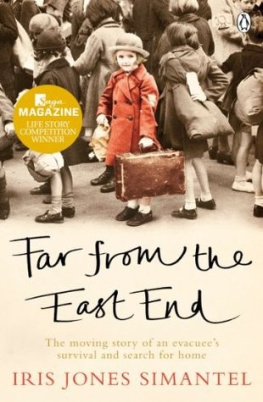

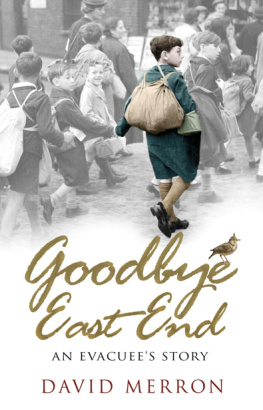

IRIS JONES SIMANTEL

Far from the East End

The Moving Story of an Evacuees Survival and Search for Home

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

FAR FROM THE EAST END

Iris Jones Simantel grew up in Dagenham and South Oxhey, but now resides in Devon where she enjoys writing as a pastime. Her memoir about her childhood beat several thousand other entries to win the Saga Life Stories Competition.

In loving memory of my dear parents, Kit and Ted Jones, who did the best they could

To my brother Peter, who will understand

and

To my brothers, Robert and Christopher, who perhaps will not To my lovely other parents, Nell and Dilwyn Cooper of Maerdy, South Wales, who provided me with a safe and caring home during the Second World War

and

To all my fellow evacuees whose lives were disrupted, altered and traumatized by the events of the Second World War,

and especially

To one of them, Ralph Laurence Brooks, who became my life partner To my children, Wayne and Robin, and my beautiful granddaughters, Erin, Devon and Chelsea, who have brought joy to my life and

To the memory of my dear childhood friend, Sheila McDonald Cinnamond, who left this world too soon

Preface

Old Londons East End was a maze of filthy, overcrowded tenements. Its streets and myriad seamy back alleys were strewn with rotting garbage while the stench and sight of raw sewage in the gutters assaulted the senses.

Its sombre huddled buildings wore the mourning-black soot from a million chimneys that had, for decades, belched clouds of smoke. The busy River Thames, Englands main artery to the world, flowed through it all, bringing trade, rats, disease and more stinking rubbish to its banks and docks, as well as thousands of immigrants from the Far and Middle East.

These slums had supposedly been cleaned up during Queen Victorias reign but they were still like an open cesspit, with fetid odours and disease-ridden air, a silent killer that stalked the streets. This hellhole was home to Londons poorest, but its people were proud and brave. It had also become home to the scum of the earth.

Death was a frequent visitor to almost every family. They died from disease, starvation, murder or injury; the hopeless were often found floating in the murky waters of the river. Crime was rampant, especially around the docklands; the streets were not safe to walk at night. Little value was placed on the lives of Londons poor, yet those who survived, by their wits and sheer determination, became, and still are, famous for their humour, creativity and ability to make do. Consider the complexity of Cockney rhyming slang: it is a language unto itself, created as a secret code between the entrepreneurs of Londons back streets. You could buy or sell anything in London and might have been killed for it.

Nevertheless, there existed another side to the darkness of this ghetto, the side that turned its international babel into a comical common language. Its misery became laughter; its infamy, fame; and its unrecorded stories evolved into song and literature. That side of Londons underbelly was to be found in its street markets, with their sharp-witted barrow boys; its pubs, with their poets and songsters; its music halls, with their comedians, musicians and actors. Here lay the creativity and the fine art of survival that were the foundations of the East Enders indomitable spirit.

This was the London of my family history. Into this history, I was born. This is my proud heritage.

Iris Jones Simantel

1

Born a Cockney Girl

Only those born within the sound of Bow Bells are properly called Cockneys.

The Victorian Dictionary

It all began on 5 July 1938, and its Gods honest truth, according to my mother, that my first life-journey almost terminated in a toilet bowl. Thinking she needed to move her bowels, she sat straining on the porcelain throne until caught there by a vigilant nurse, who threw up a verbal roadblock: Stop pushing, Mother. I can only imagine what a shitty view of the world I might have had were it not for that nurse and her timely intervention.

I managed a more appropriate debut in the delivery room at the East End Maternity Hospital in Poplar, East London. Located within the sound of Bow Bells (St Mary-le-Bow Church), it bestowed upon me the dubious label Cockney, which carried many less-than-desirable connotations.

The fact is, I should never have been a Cockney. My family had moved from the old East End before my conception and now lived in Dagenham, Essex, eight miles away from the sound of Bow bloody Bells, hence eight miles outside Cockney territory. However, with Dad working out of town, Mum feared being alone when she received the warning signals that I was en route. Also, there would be no one to care for Peter, my four-year-old brother. She decided to stay with her parents, who lived on Blackwall Pier in Poplar, close to the maternity hospital and, of course, well within the sound of Bow Bells. She still found herself alone when she felt the first contractions. Afraid, not knowing when someone might come home, she set out alone, small shabby suitcase in hand, to catch a bus to the hospital.

As she stood waiting at the bus stop, her sisters fianc, Walter, happened along the road in his car. He stopped in front of Mum and lowered the window. Where are you off to, Kitty?

Oh, ello, Walt, Im going to the ospital, replied Mum, in her strong Cockney accent. I think me times come.

Why are you going alone? Wheres Ted? Does anyone know youre going?

I dont think so, Walt, she said. Teds workin away, Mum went down Chrisp Street with Peter to do a bit of shoppin, and me dads at work, so I thought Id just catch the bus so I wouldnt ave to bother no one.

Did you leave a note to say where you were going?

Oooh, no, I spose I shouldve but I didnt think of it.

Well, come on, climb in and Ill take you.

Are you sure? I dont wanna put you out.

Walter convinced her it would be no trouble at all, and she loaded her sizeable self into the car.

After he had deposited her at the hospitals entrance, Walter rushed back to the house, found her parents his own future in-laws and informed them their daughter was about to deliver their second grandchild.

Silly cow. I thought shed gone out to buy some fags, my grandmother responded, rolling her eyes and tutting in disbelief.

After a quick visit to the hospital to see Mum and me, Granddad went off to send Dad a telegram. A few days later Mum received a letter from him, the only letter he ever wrote to her; she kept it all her life, passing it on to me shortly before her death. The envelope bore a penny-hapenny stamp, and the letter, written in pencil, reads in part, Well, I couldnt have done anything if I was there could I?

So, that was how it happened, and how I became a Cockney instead of the Essex Girl I should have been. Years later, I learned that an Essex Girl had lower-class origins and a reputation for being fast and loose. One might say Id been saved by the Bells.

When Mum was discharged from the maternity hospital, she, Peter and I stayed on with Nan and Granddad at Blackwall Pier until Dad came home. Nan and Granddad lived in the station masters house at Blackwall railway station, where Granddad worked as station master. Situated on Brunswick Wharf, the house and station were part of the historic East India Docks on the River Thames. Brunswick Wharf was where Captain John Smith set sail on his voyage to America to establish the first British settlement in Virginia. It was also where the Indian princess Pocahontas first set foot in England with her British husband, Captain John Rolfe. You could say Pocahontas and I had something in common in that we both made our London debut at the same address.

Next page