A FTERWORD

by Richard Howard

English-speaking readers invariably characterize Stendhals works, and especially The Charterhouse of Parma, by the words gusto, brio, lan, verve, panache. These are, of course, all foreign terms, never translated, though so necessary that they have been readily naturalized. It will be the translators aim, indeed the translators responsibility, so to characterize any future translation of Stendhal, who wrote his last completed novel in fifty-two days, a miracle of gusto, brio, lan, verve, panache.

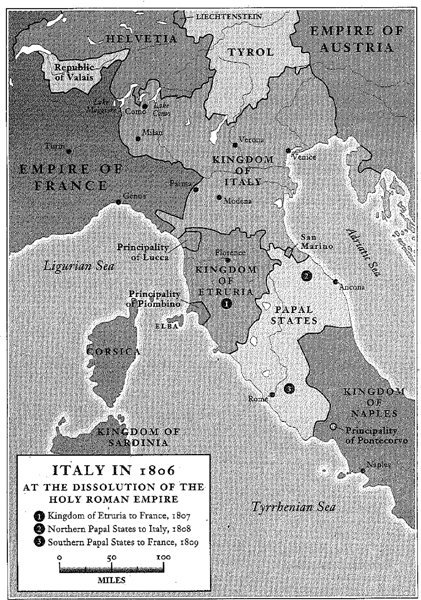

Like miracles generally, the novel is mysterious, beginning with its title: the Carthusian Monastery of Parma, the Charterhouse, appears only on the last page of the book, three paragraphs from the end. To this sequestration Fabrizio del Dongo retires, lives there a year, dies there (he is twenty-seven years oldthe age of the oldest French generals in Napoleons army entering Milan in Chapter One). Stendhal had initially wanted to call his novel The Black Charterhouse, a clue: in the prison from which Fabrizio so spectacularly escapes, there is indeed a black chapel. Fabrizios nine months imprisonment in the Farnese Towermore than one critic has observedis analogous to the Carthusian monks discipline in their monastery: by this means he is reborn, he achieves freedom, happiness, and love.

Throughout the novel, incidents and details recur, repeat themselves, recall some earlier instance. Certain verbal echoes may keep the reader conscious of the pattern: Fabrizios first imprisonment and his night with the jailers wife will become Fabrizio in the Farnese Tower, loving Cllia; the del Dongo castle at Grianta towering above Lake Como becomes the Citadel of Parma; the astronomy lessons on the platform of one of the castles gothic towers become Abb Blanss observatory on top of the town bell tower, then the platform of the citadel on which the Farnese Tower is erected. Towers, platforms, windows; height, imprisonment, flight; divination, hiding, vision: these images and themes weave the novel together. The same words are used in widely separated situations: the translator must make sure they recur in his version.

Nothing fixed. The man, Nietzsche said, was a human question-mark. And he suggested the tone, the reason for it and the consequence of it: Objection, evasion, joyous distrust, and love of irony are signs of health; everything absolute belongs to pathology.

Consider Ginas two husbands: Count Pietranera, who prefers living in poverty to political compromise, and Count Mosca, for whom politics is a game and any conviction a liability. All political life is marked by incoherence. As Professor Talbot puts it, conservatives become liberals when out of power, and liberals become conservatives when in power.

Consider, again, Fabrizios roles; in the first third of the novel he claims to be a barometer merchant, a captain of the Fourth Regiment of hussars, a young bourgeois in love with that captains wife, Teulier, Boulot, Cavi, Ascanio Pietranera, and an unnamed peasant. Further, he will assume a disguise to visit Mariettas apartment, will use Gilettis name and passport to go through customs, assume another disguise as a rich country bourgeois; then claim to be Ludovics brother, then Joseph Bossi, a theology student. With Fausta, he passes himself off as the valet of an English lord; in the duel with Count M he calls himself Bombace. And under all this, his conviction that he is a del Dongo. Nor is he even thathe is the son of a French lieutenant named Robert billeted in the del Dongo palace in Milan during the French occupation; therefore Gina is not his aunt, though on one occasion early in the novel she passes Fabrizio off as her son! Evading the love of a woman he believes to be his aunt, Fabrizio ends in a prison originally built to house a crown prince guilty of incest.

Nothing fixed: Fabrizio is not a soldier, though he may have fought at Waterloo; not for a moment do we believe he is a cleric, though he is made archbishop of Parma; he is pure becoming, and the language he uses must show him to us in that form, that formlessness.

Translate this book to exorcise the fetishism of the Work conceived as an hermetic object, finished, absolute (Beyle, the anti-Flaubert). Nothing in this novel, complete though it may be, is quite closed over itself, autonomous in its genesis, and its signification. Hence Balzacs suggestion to erase Parma altogether and call the book something like Adventures of a typical Italian youth. Remember that the novel opens as the story of the Duchess Sanseverina. And ends with the throttled disappearance (Beyles phrase, in protest against the publishers insistence that the book fit in two volumes) of everyone but Mosca, immensely rich. Such vacillation is never satisfied. More than Vanity Fair, this is a Novel Without a Hero, without a Heroine, a novel without

Realism, but no reality. The first text by him I ever translated, for Ben Sonnenbergs Grand Street, was that extraordinary list of twenty-three articles headed Les Privilges. That ought to have done it: God would exist and Beyle would believe in Him if he never had to suffer a serious illness, only three days indisposition a year. If his penis would be allowed to grow erect at will, be two inches longer, and give him pleasure twice a week If he could change into any animal he chose If he would no longer be plagued by fleas, mosquitoes, and mice etc., etc.

Then I translated one of the dozens of unfinished books by one of dozens of pseudonyms (as many as Kierkegaard, as many as Pessoa!), texts abandoned after no more than a torso had been molded, the armature of inspiration forsworn once the rapture waned (The Pink and the Green).

The invitation in both these texts, preposterous and unfinished alike, to enter (and for the translator, it is virtually a welcome) into the banausics of the affair A kind of painful tension under the disguise of the driest, or the wettest, style. What Valry calls the restlessness of a superior mind; in any case an ineloquent one. You could place Stendhal by saying he is utterly alien to eloquence (Hugo, who had no use for him, said he lacked style; Stendhal delighted in the compliment, as in this scribbled note: A young woman murdered right next to meshe is lying in the middle of the street and beside her head a puddle of blood about a foot across. This is what M. Victor Hugo calls being bathed in ones own blood). An author who must be continually reread, for he never repeats, and as Alain observes, never develops.

Its not style he lacks, but rhythm: Stendhal never sweeps you awayhe doesnt want to sweep you away: that would be against his principles. He engages your complicity, and for that you must be all attention. Follow him down the page, in the sentence, across the synapses of the amazing clauses, and the sense, the wit, the literature occurs in the gaps between the statements, very abruptly juxtaposed:

A man of parts, he had formerly shown courage in battle; now he was inveterately in a state of alarm, suspecting he lacked that presence of mind commonly deemed necessary to the role of ambassadorM. de Talleyrand has spoilt the professionand imagining he might give evidence of wit by talking incessantly.

Grasshopper prose, and there is no pleasure to be taken in it if it is not attended to by presence of mind. As the reference to Talleyrand suggests, we are being taken into the authors confidence, entrusted with the supposition of intellectwhat other author flatters us to this degree?