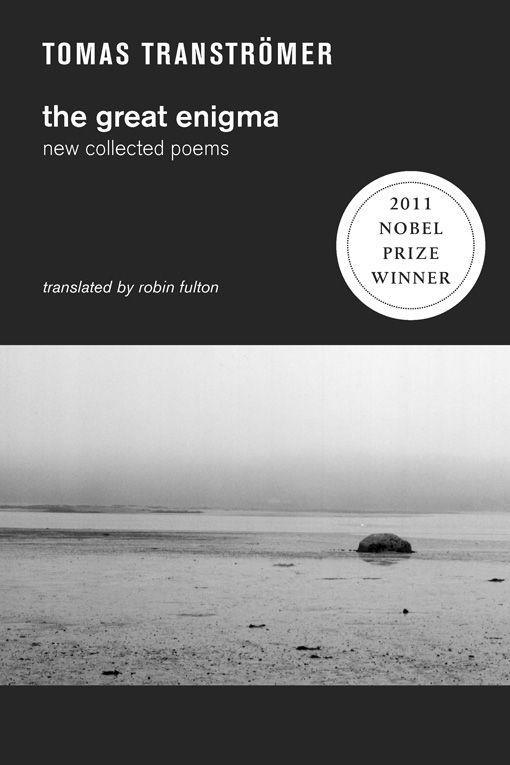

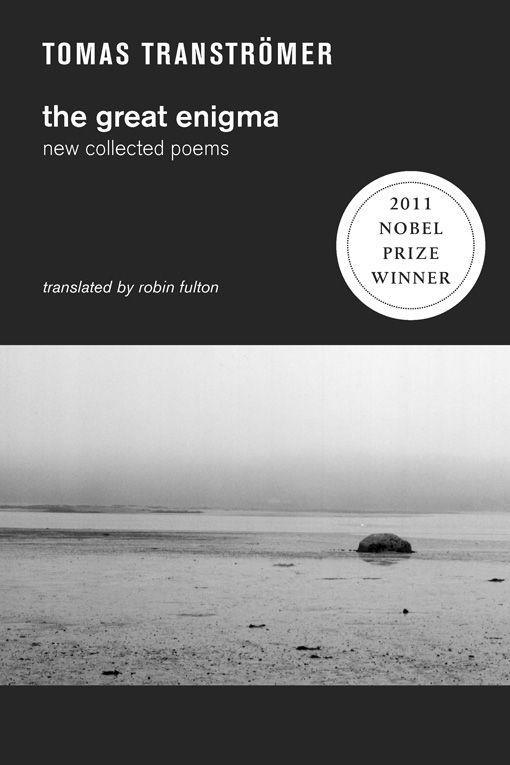

Tomas Transtrmer The Great Enigma New Collected Poems Translated from the Swedish by Robin Fulton

Tomas Transtrmer The Great Enigma New Collected Poems Translated from the Swedish by Robin Fulton  A New Directions Book

A New Directions Book  Copyright 1987, 1997, 2002, 2006 by Tomas Transtrmer Translation copyright 1987, 1997, 2002, 2006 by Robin Fulton All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, or television review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems is published by arrangement with Bloodaxe Books Ltd., Highgreen, Tarset, Northumberland, NE48 1RP, UK. eBook conversion by Robert Kern, TIPS Technical Publishing, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America. New Directions Books are printed on acid-free paper.

Copyright 1987, 1997, 2002, 2006 by Tomas Transtrmer Translation copyright 1987, 1997, 2002, 2006 by Robin Fulton All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, or television review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems is published by arrangement with Bloodaxe Books Ltd., Highgreen, Tarset, Northumberland, NE48 1RP, UK. eBook conversion by Robert Kern, TIPS Technical Publishing, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America. New Directions Books are printed on acid-free paper.

First published as a New Directions Paperbook (NDP1050) in 2006. Published simultaneously in Canada by Penguin Books Canada Limited. e-ISBN: 978-0-8112-2017-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Transtrmer, Tomas, 1931- [Poems. English. Selections] The great enigma : new collected poems / Tomas Transtrmer ; translated from the Swedish by Robin Fulton. cm. cm.

Includes index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8112-1672-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8112-1672-1 (alk. paper) 1. Transtrmer, Tomas, 1931Translations into English. I.

Fulton, Robin. II. Title. pt9876.3.r3a2 2006 839.71'74--dc22 New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin by New Directions Publishing Corporation 80 Eighth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 www.ndbooks.com Contents (17 DIKTER) , 1954 I II : III IV V (HEMLIGHETER P VGEN) , 1958 I II III IV V VI (FNGELSE) , 1959 (DEN HALVFRDIGA HIMLEN) , 1962 I II III IV V (KLANGER OCH SPR), 1966 (MRKERSEENDE) , 1970 (STIGAR) , 1973 (STERSJAR) , 1974 (SANNINGSBARRIREN) , 1978 I II III IV (DET VILDA TORGET) , 1983 I II III IV (FR LEVANDE OCH DDA) , 1989 (SORGEGONDOLEN) , 1996 (DEN STORA GTAN) , 2004 PROSE MEMOIR

(MINNENA SER MIG) , 1993 Foreword Over forty years ago Tomas Transtrmer wrote a poem called Morning Birds, which concludes with the idea of the poem growing while the poet shrinks: It grows, it takes my place. It pushes me aside. It throws me out of the nest.

The poem is ready. He could hardly have envisaged then how aptly these lines would describe his career. On the one hand we have the private person who was born in Stockholm in 1931, who spent many years in Vsters working as a psychologist, and who has now returned to Stockholm to live in the very area in which he grew up. The same private person has spent as much time as possible out in the Stockholm Archipelago, on Runmar, an island rich in family associations and a place which, I suspect, he feels is his real home. As part of the private persons story it has to be recorded that just short of his sixtieth birthday he suffered a stroke which deprived him of most of his speech and partly inhibited movement on his right side. On the other hand we have the poet whose gathered work takes up very little space on the bookshelfas he says in the memoir of his grammar-school days, he became well-known for deficient productivityand yet this poets seemingly modest body of work has generated enormous interest.

For over half a century, as they slowly accumulated, his poems have attracted special attention in his native Sweden, and in the course of the last three decades they have caught the interest of an extraordinary range of readers throughout the world. The ever-widening response to Transtrmers poems has been meticulously documented by Lennart Karlstrm: the first two volumes of his bibliography, taking us up to 1999, amount to almost eight hundred pages and list translations into fifty languages. Transtrmer is perhaps less in need of selection or pruning than any other poet. A new reader, however, might not want to proceed through this volume in a straight chronological manner. Reading back from recent to early work could be more helpful than reading forward (as in the arrangement of May Swensons selection Windows and Stones, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1972). 17 Poems (1954) gathered pieces written by Transtrmer in his late teens and very early twenties and immediately announced the presence of a distinct poetic personality. 17 Poems (1954) gathered pieces written by Transtrmer in his late teens and very early twenties and immediately announced the presence of a distinct poetic personality.

The three longer pieces that conclude the collection suggest a kind of poetic ambition which the young Transtrmer soon losthis notes on my first version of Elegy, for instance, contain remarks like: This poem was written by a romantic 22-year-old! and Oh dear, how complicated I was in my younger days.... But the very first poem, suitably called Prelude, reveals a quality characteristic of all his writing: the very sharply realized visual sense of his poems. The images leap out from the page, so the first-time reader or listener has the immediate feeling of being given something very tangible. Prelude also points forward thematically. It describes the process of waking up (note how this process appears not in the usual terms of rising to the surface but in terms of falling, of a parachute jump down into a vivid and teeming world). And this fascination with the borders between sleep and waking, with the strange areas of access between an everyday world we seem to know and another world we cant know in the same way but whose presence is undeniablesuch a fascination has over the decades been one of Transtrmers predominant themes.

Dream Seminar, for example, from The Wild Market Square (1983) deals directly with certain aspects of the relations between waking and dreaming states, but the reader will soon discover many poems which explore this region. The way in which Transtrmer describes, or allows for, or tries to come to terms with the powerful elements of our lives that we cannot consciously control or even satisfactorily define suggests, rightly, that there is a profoundly religious aspect to his poems. In a largely secular country like Sweden such a writer may well be asked about religion in a rather blunt or naive manner (as if Do you believe in God? were the same kind of question as Do you vote Social Democrat?) and Transtrmer has always replied to such questions cautiously. The following, from an interview with Gunnar Harding in 1973, is a characteristic response to the comment that reviewers sometimes refer to him as a mystic and sometimes as a religious poet: Very pretentious words, mystic and so on. Naturally I feel reserved about their use, but you could at least say that I respond to reality in such a way that I look on existence as a great mystery and that at times, at certain moments, this mystery carries a strong charge, so that it does have a religious character, and it is often in such a context that I write. So these poems are all the time pointing toward a greater context, one that is incomprehensible to our normal everyday reason.

Although it begins in something very concrete. This movement toward a larger context is very important, and it reflects Transtrmers distrust of oversimplified formulations, slogans, and rhetorical gestures as shortcuts that can obscure and mislead. It is in similar terms that we can see his response (or perhaps refusal to respond directly) to the criticism of several reviewers of the late 1960s and early 1970s that his poetry ignored current political realities. The assumption behind such criticism was that poetry is just another element of political debate, and its use of language is no different from an editorial. Many of his poems do deal with current realities, but with a careful avoidance of the simplifications and aggressions of politicized language and with an awareness of a wider and deeper context that seemed beyond the range of the directly engaged poetry of the period, with its concern for taking positions on a black-and-white and rather parochial political map. See in particular About History from Bells and Tracks (1966), and then By the River, Outskirts, Traffic, and Night Duty from Seeing in the Dark (1970).

Next page

Tomas Transtrmer The Great Enigma New Collected Poems Translated from the Swedish by Robin Fulton

Tomas Transtrmer The Great Enigma New Collected Poems Translated from the Swedish by Robin Fulton  A New Directions Book

A New Directions Book  Copyright 1987, 1997, 2002, 2006 by Tomas Transtrmer Translation copyright 1987, 1997, 2002, 2006 by Robin Fulton All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, or television review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems is published by arrangement with Bloodaxe Books Ltd., Highgreen, Tarset, Northumberland, NE48 1RP, UK. eBook conversion by Robert Kern, TIPS Technical Publishing, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America. New Directions Books are printed on acid-free paper.

Copyright 1987, 1997, 2002, 2006 by Tomas Transtrmer Translation copyright 1987, 1997, 2002, 2006 by Robin Fulton All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, or television review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems is published by arrangement with Bloodaxe Books Ltd., Highgreen, Tarset, Northumberland, NE48 1RP, UK. eBook conversion by Robert Kern, TIPS Technical Publishing, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America. New Directions Books are printed on acid-free paper.