Books by Elizabeth Warnock Fernea

Remembering Childhood in the Middle East: Memoirs

from a Century of Change

Guests of the Sheik: An Ethnography of an Iraqi Village

The Arab World: Forty Years of Change

(with Robert A. Fernea)

The Struggle for Peace: Israelis and Palestinians

(with Mary Evelyn Hocking)

A Street in Marrakech

Children of the Muslim Middle East

Nubian Ethnographies

(with Robert A. Fernea)

A View of the Nile

Middle Eastern Muslim Women Speak

(with Basima Qattan Bezirgan)

Women and the Family in the Middle East: New Voices of

Change

In Search of Islamic Feminism: One Womans Global

Journey

A NCHOR B OOKS E DITIONS , 1969, 1989

Copyright 1965 by Elizabeth Warnock Fernea

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Doubleday in 1965. The Anchor Books edition is published by arrangement with Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fernea, Elizabeth Warnock.

Guests of the Sheik: an ethnography of an

Iraqi village / Elizabeth Warnock Fernea.

p. cm.

Reprint. Originally published: 1969.

1. WomenIraqNahr. 2. Nahr (Iraq)

Social life and customs.

I. Title.

HQ1735.Z9N344 1989 89-27687

306.095675dc20

eISBN: 978-0-307-77378-4

Copyright 1965 by Elizabeth Warnock Fernea

www.anchorbooks.com

v3.1

For My Mother,

Elizabeth Warnock

Contents

INTRODUCTION

I spent the first two years of my married life in a tribal settlement on the edge of a village in southern Iraq. My husband, a social anthropologist, was doing research for his doctorate from the University of Chicago.

This book is a personal narrative of those years, especially of my life with the veiled women who, like me, lived in mud-brick houses surrounded by high mud walls. I am not an anthropologist. Before going to Iraq, I knew no Arabic and almost nothing of the Middle East, its religion and its culture. I have tried to set down faithfully my reactions to a new world; any inaccuracies are my own.

The village, the tribe and all of the people who appear in the following pages are real, as are the incidents. However, I have changed the names so that no one may be embarrassed, although I doubt that any of my women friends in the village will ever read my book.

Without their friendship and hospitality, and that of other Iraqi and American friends too numerous to mention, this book quite literally would never have been written. I want to thank my friend Nicholas B. Millet for drafting the sketch-map which has been used on in this book. I owe a special debt of gratitude to two people. Audrey Walz (Mrs. Jay Walz) read the incomplete manuscript and advised me to finish it. Her enthusiasm, together with her sound judgment and critical ear, have aided the books progress immeasurably. My husband, Robert Fernea, first encouraged me to write Guests of the Sheik. His interest and his intellectual honesty helped me face the realities of living in El Nahra and, later, of trying to shape that experience into the book which follows.

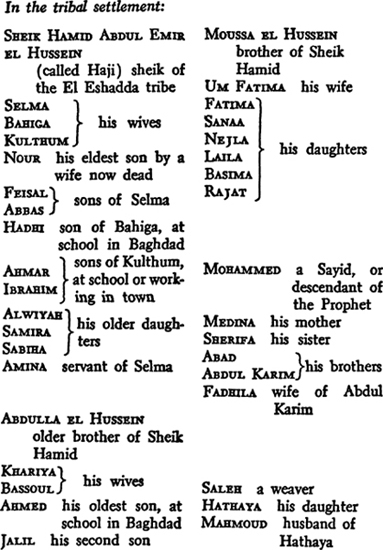

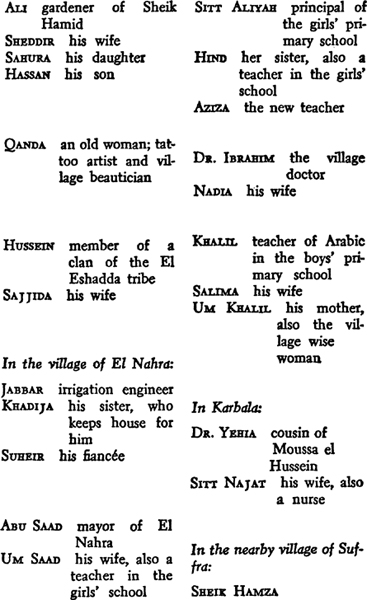

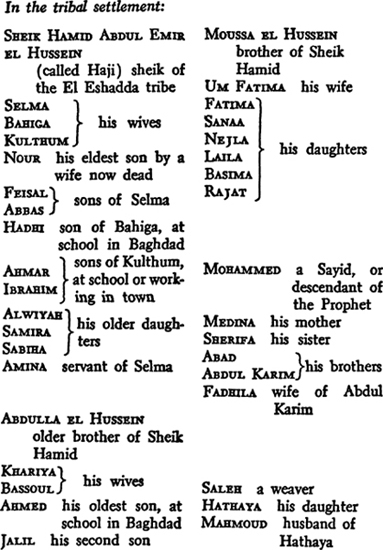

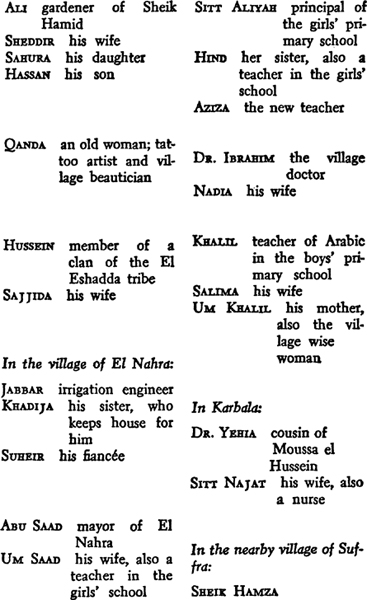

CAST OF CHARACTERS

PART I

1

Night Journey: Arrival in the Village

The night train from Baghdad to Basra was already hissing and creaking in its tracks when Bob and I arrived at the platform. Clouds of steam billowing from the engine hung suspended in the cold January air as we hurried across, laden with suitcases, bundles, string bags and an angel-food cake in a cardboard box, a farewell present from a thoughtful American friend. We were on the last lap of our journey, and I found myself half dreading and half anticipating the adventure we had come almost ten thousand miles to begin.

Diwaniya! Diwaniya!

Those are the coaches we want, said Bob, taking my arm and steering me down the platform past crowds of tribesmen arguing heatedly or sitting in tight quiet groups, their wives swathed in black to the eyebrows, with children on hip and shoulder; past the white-collar Iraqi effendis in Western suits and past the shouting German tourists.

An attendant in an ill-fitting khaki wool uniform helped us board and guided us to a compartment, where he dusted the worn leather seats with his coat sleeve. We sat down. I found my stomach was churning and I glanced quickly at Bob to see how he was taking the long-awaited departure.

I knew he was nervous about my reception in El Nahra, the remote village where we were now headed and where he had been living and working as an anthropologist for the past three months. He was no more nervous than I, who knew little of El Nahra except that no one spoke English there, that the people were of the conservative Shiite sect of Islam, and that the women were heavily veiled and lived in the strictest seclusion. No Western woman had ever lived in El Nahra before and very few had even been seen there, Bob said, which meant I would be something of a curiosity. I wasnt sure I wanted to be. And we were to be guests of Sheik Hamid Abdul Emir el Hussein, chief of the El Eshadda tribe, who had offered us a mud house with a walled garden. Our first home, said Boba honeymoon house. But who had ever heard of a honeymoon house made of mud?

Hil-lal Diwaniya! Samawa! Bas-ra! bawled the conductors. Yallah! The train began to move past the station and the line of waiting taxis and horse-drawn carriages.

Well, were off, announced Bob, a little too heartily. He motioned to the hovering porter and ordered some beer to celebrate our departure. Maybe well have some rain before we get to Diwaniya. He stood up to peer out of the window.

I looked out, tooexpecting what? A friend to wave goodbye? Three months ago I had come to Baghdad as a bride and the city had seemed strange and alien to me then, a place so far removed from my experience that I had nothing with which to compare it. Now, headed for an unknown tribal village, I did not want to miss my last glimpse of Baghdad, which seemed a dear familiar place.

Clouds hung low and dark in the bit of sky I could see between the buildings and the townspeople and tribesmen, carriages, cars and donkey carts that moved more and more quickly past the train window. The winter night was coming fast, and as we left the Tigris River behind, the lights were on in all the hotels along its banksthe Semiramis, the Zia, the Sindbad. We passed rows of mud-and-mat serifa huts with kerosene lanterns flickering in their doorways, a series of smoking brick kilns, a mosque with a lighted minaret, more serifa huts, and then there was nothing to see but the dark horizon and a few date palms and the wide, empty plain.