Copyright 2012 by Timothy Egan

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Egan, Timothy.

Short nights of the Shadow Catcher : the epic life and immortal photographs of Edward Curtis / Timothy Egan.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-618-96902-9 (hardback)

1. Curtis, Edward S., 18681952. 2. PhotographersUnited States Biography. 3. Indians of North AmericaPictorial works. I. Title.

TR140.C82E43 2012

770.92dc23 2012022390

eISBN 978-0-547-84060-4

v1.1012

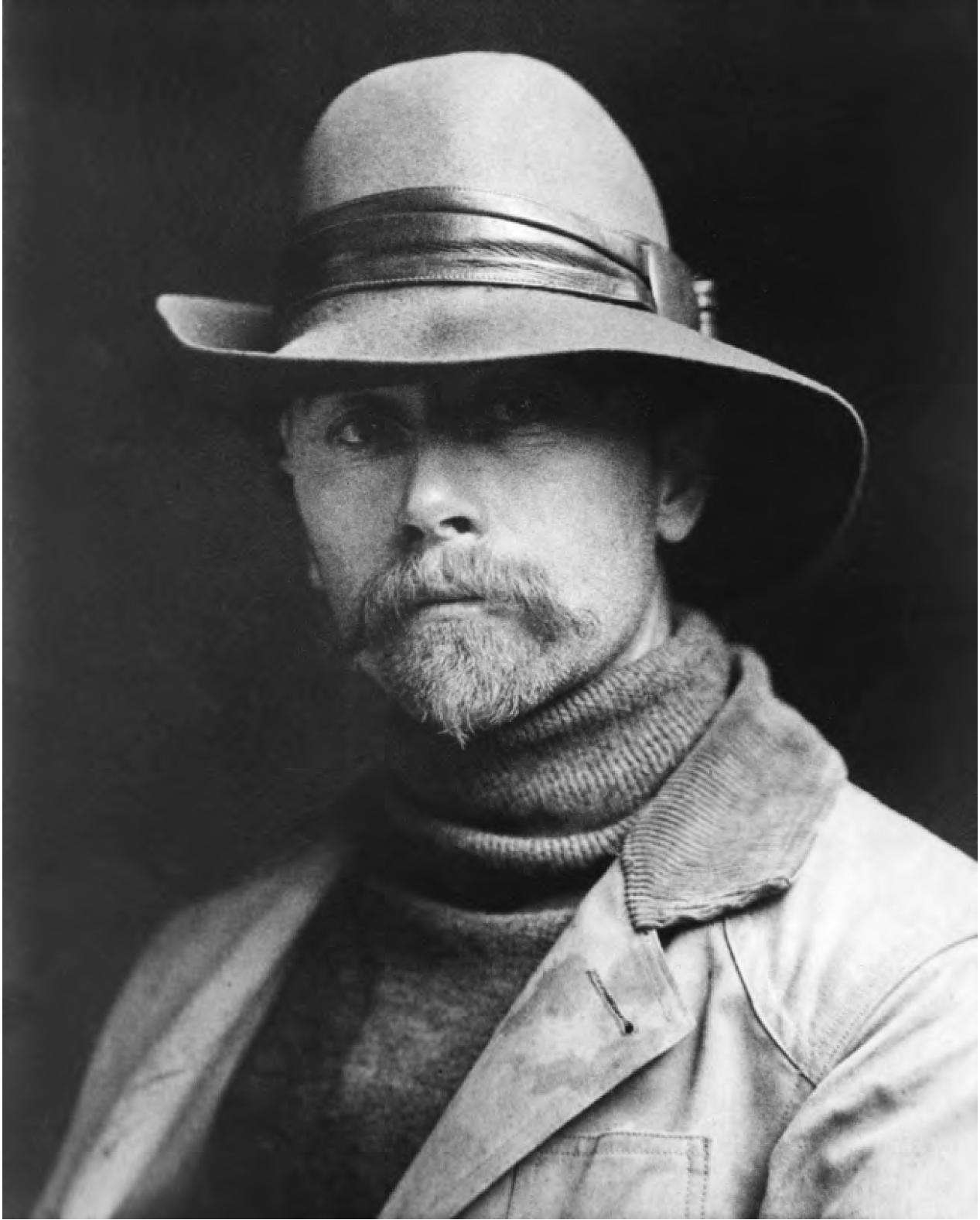

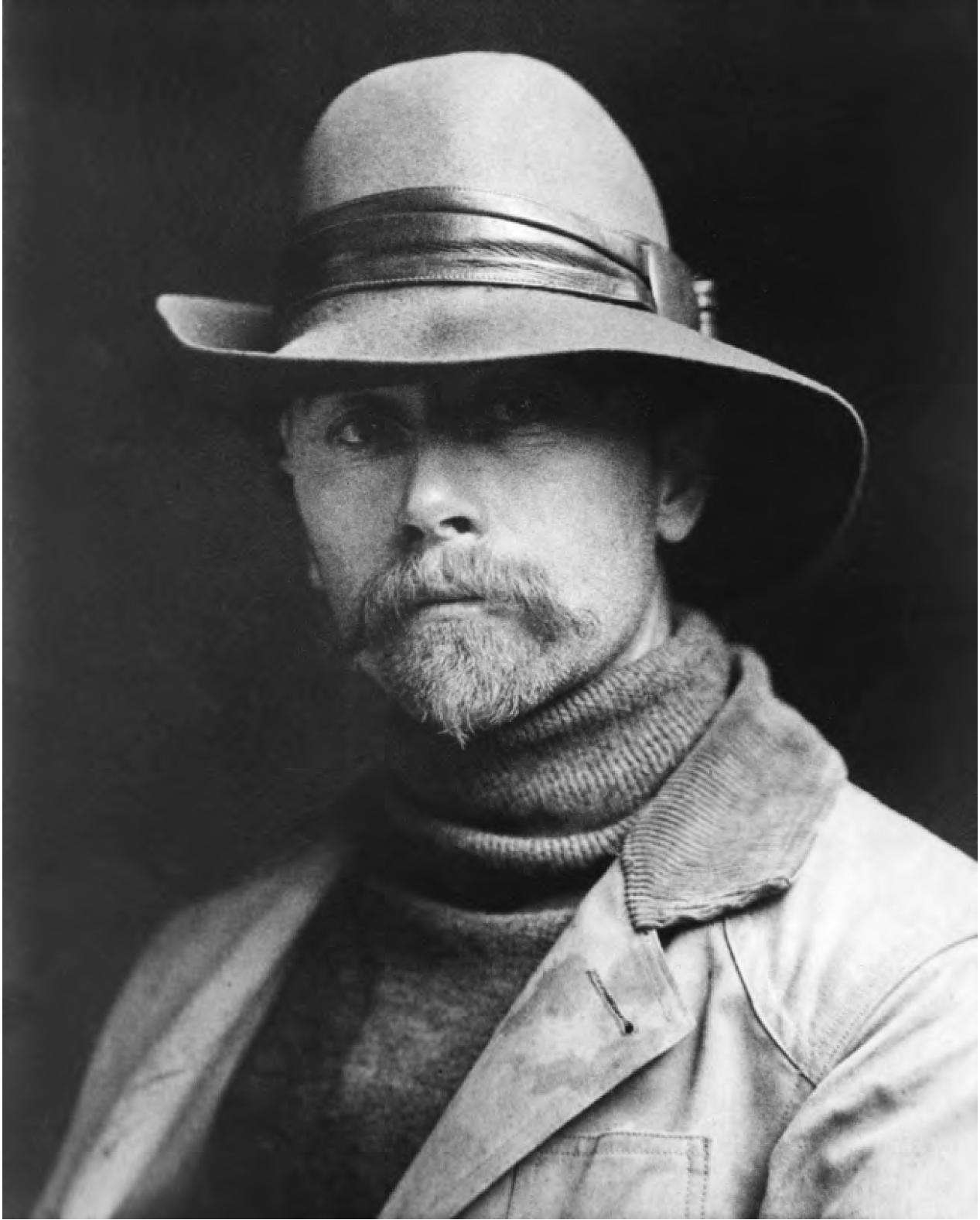

Frontispiece: Edward S. Curtis, self-portrait, 1899

In memory of Joan Patricia Lynch Egan, mother of seven, who filled us with the Irish love of the underdog and of the written word. She was sustained by books until the very end.

We are vanishing from the earth, yet I cannot think we are useless or else Usen would not have created us. He created all tribes of men and certainly had a righteous purpose in creating each.

GERONIMO APACHE

What is life? It is the flash of a firefly in the night. It is the breath of a buffalo in the wintertime. It is in the little shadow which runs across the grass and loses itself at sunset.

CROWFOOT BLACKFEET

1. First Picture

1896

T HE LAST INDIAN OF Seattle lived in a shack down among the greased piers and coal bunkers of the new city, on what was then called West Street, her hovel in the grip of Puget Sound, off plumb in a rise above the tidal flats. The cabin was two rooms, cloaked in a chipped jacket of clapboards, damp inside. Shantytown was the unofficial name for this part of the city, and if you wanted to dump a bucket of cooking oil or a rusted stove or a body, this was the place to do it. It smelled of viscera, sewage and raw industry, and only when a strong breeze huffed in from the Pacific did people onshore get a brief, briny reprieve from the residual odors of their labor.

The city was named for the old womans father, though the founders had trouble pronouncing See-ahlsh, a kind of guttural grunt to the ears of the midwesterners freshly settled at the far edge of the continent. Nor could they fathom how to properly say Kick-is-om-lo, his daughter. So the seaport became Seattle, much more melodic, and the eccentric Indian woman was renamed Princess Angeline, the oldest and last surviving child of the chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish. Seattle died in 1866; had the residents of the village on Elliott Bay followed the custom of his people, they would have been forbidden to speak his name for at least a year after his death. As it was, his spirit was insulted hourly, at the least, on every day of that first year. Princess was used in condescension, mostly. How could this dirty, toothless wretch living amid the garbage be royalty? How could this tiny beggar in calico, bent by time, this clam digger who sold bivalves door to door, this laundress who scrubbed clothes on the rocks, be a princess?

The old crone was a common term for Angeline.

Ragged remnant of royalty was a more fanciful description. She was famous for her ugliness. Nearly blind, her eyes a quarter-rise slit without noticeable lashes. Said to have a single tooth, which she used to clamp a pipe. A face often compared to a washrag. The living mummy of Princess Angeline was a tourist draw, lured out for the amusement of visiting dignitaries. When she met Benjamin Harrison, the shaggy-bearded twenty-third president of the United States, during his 1891 trip to Puget Sound, the native extended a withered hand and shouted Kla-how-ya, a traditional greeting. Though she clearly knew many English phrases, she refused to speak the language of the new residents.

Nika halo cumtuv, her contemporaries quoted her as saying. I cannot understand.

Angeline was nearly alone in using words that had clung like angel hair to the forested hills above the bay for centuries. Lushootseed, the Coast Salish dialect, was her native tongue, once spoken by about eight thousand people who lived all around the inland sea, their hamlets holding to the higher ground near streams that delivered the tyee, also called the Chinook or king salmon, to the doorsteps of their big-boned timber lodges. Angeline came to our house shortly before her death, a granddaughter of one of the citys founders remembered. She sat on a stool and spoke in native tongue. We forgot her ugliness and her grumpiness and realized as never before the tragedy of her life and that of all Indians.

They could appreciate the tragedy, of course, in an abstract, vaguely sympathetic way, because they had no doubt that Indians would soon disappear from what would become the largest city on the continent named for a Native American. Well before the twentieth century dawned, there was a rush to the past tense in a country with plenty of real, live indigenous people in its midst. Angeline, by the terms of the Point Elliott Treaty of 1855, was not even allowed to reside in town; the pact said the Duwamish and Suquamish had to leave, get out of sight, move across the bay to a sliver of rocky ground set aside for the aborigines. The bands who had lived by the rivers that drained the Cascade Mountains gave up two million acres for a small cash settlement, one blanket and four and a half yards of cloth per person. Eleven years later, Seattle passed a law making it a crime for anyone to harbor an Indian within the city limits.

Angeline ignored the treaty and the ordinance. She refused to move; she had no desire to live among the family clans and their feuds on the speck of reservation land that looked back at the rising sun. The Boston Men, as older Indians called the wave of Anglos from that distant port, allowed tiny Angeline to stay puta free-to-roam sovereign outcast in the land of her ancestors. She was harmless, after all: a quaint, colorful connection to a vanquished past. Poor broken Angeline. Is she still here, in that dreadful shack? God, what a piteous sight. She was even celebrated in verse by the early mythologists of Seattle:

Her wardrobe was a varied one

Donated by most everyone.

But Angeline deemed it not worthwhile

To put on others cast-off style!

And much preferred a plain bandanna

To kerchief silk from far Havana.

The children of the new city, the American boys in short pants, had no verse or kind words for her. Angeline was prey. Great fun. They taunted the gnarled Indian, threw rocks at her. These urchins would lurk around the waterfront after school, looking to catch Angeline by surprise, then they would fire their stones at her and watch her squawk in befuddlement.

You old hag! the boys shouted.

But she gave as good as she got. Under those layers of filthy skirts, Angeline carried rocks for self-defense. She didnt leave the shack without ammunition. She didnt hide or retreat, but instead would sink an arthritic hand into one of her many pockets, find a stone and let it rip back at the boys. Take that, you bastards! Once, she hit Rollie Denny, he of the founding family whose name was all over the plats of the fast-expanding city. Hit him square with a rock for all to see, at the corner of Front Street and Madison. This also became part of the verse, the poetic myth: the crippled, sickly, elfin descendant of Chief Seattle nailed the snot-nosed kid, heir to much of the land taken from the native people.

For once he hit her with a stone

Next page