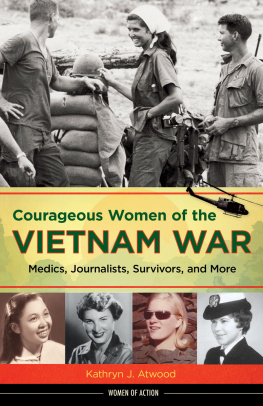

Millions of words have been printed and published about the Vietnam War. So why more words from me? You may think, Old big mouth is at it again, but I do have a good reason for writing a foreword to this book. It's to help give some public recognition where it's long overdueto the American women who served so admirably in Vietnam.

Reading these interviews brought back a flood of memories for me. I know what these women experienced (and the memories they carry with them), because I was there too. I was in that war-torn country each year from 1965 until the end of the war. I spent over two years of my life there, entertaining, nursing, visiting bases, camps, and field units all over Vietnam. I saw these dedicated women at their workplacesthe hospitals, staff offices, USO centers, Red Cross units. I saw what they did and how much they were needed.

I've often said that these American women should have been given a ticker tape parade when they returned home! But that didn't happenthey have never received any recognition. In Vietnam the troops let us know we were appreciated; we could be proud of what we were doing. Back in the U.S., everyone wanted to forget the war. Now, ten years later, people are asking what happened there. I think it's important that they know women did their share, more than their share, if that's possible. Our country owes them profound thanks. I'm proud to be part of this book because finally their story is being told.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to make a special acknowledgment here for each of those women whose stories, for varying reasons, have not been included in this book. They create, nevertheless, a collective spirit which has a most tangible presence in these pages: Carli Numi, Marianne Jacobs, Shirley Bowington, Jane Thompson, Madelon Visintainer, Saralee McGoren, Norma Griffiths-Boris, Pat Rumpza, Placida McGowan, Pamela White, Kathy Thompson, Peggy Tuxen, Elaine Davies, and Bobbi Lee.

To the women in my immediate life, my wife Anne and daughters Julie and Christina, I must pay tribute for sharing, with such delicate balance, the roller-coaster ride of emotions that I have brought home with me throughout the past three years. And thanks are also due my mother for her belief in this book from the beginning.

I owe a huge debt to all the male Vietnam veterans who have shared their lives with me. In them, I have recognized a courage and forbearance that mark the unique qualities of a truly remarkable generation of Americans. Among them, individual credit for help with this book is due: Jeff Wilcox, Jim Newman, Jeff Ramsdell, and Richard Castro.

I am grateful to Gloria Emerson for her much needed advice regarding the early manuscript and to Joan Griffin, my editor at Presidio Press, for her vision and support during each stage of its development.

Warmest regards go to Ethel and Stephen Dunn and Susan Miller for their excellent transcription and word processing services.

How do I thank a friend like Steve Ajay who has so unselfishly shared his enthusiasm and knowledge with me? I can simply say that he has made a major contribution to this book.

Finally, I would like to call attention to the extraordinary contribution that Lynda Van Devanter, army nurse at Pleiku and Vietnam veteran activist, has made. She has been a pioneer in securing recognition and support for those women, each and every one, who went to war in Vietnam. We all owe her a great deal.

INTRODUCTION

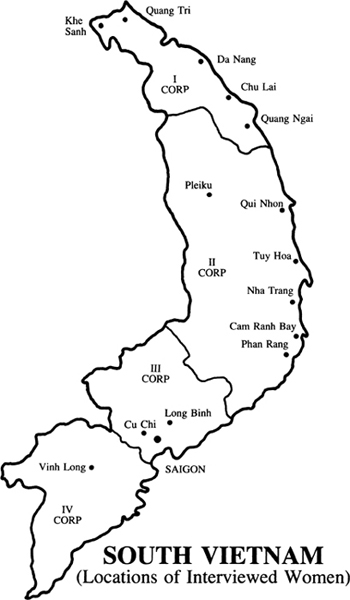

I had been involved with the Vietnam veterans community for several months, working on a photo essay about them, but had yet to locate a woman who was in Vietnam during the war. Then in February 1983, I was introduced to Rose Sandecki, director of the Veterans Outreach Center in Concord, California, and arranged an interview with her. For an hour and a half Rose told me of things I couldn't have imagined: how close to the war women actually were, the details of her daily routine as an emergency room nurse in Cu Chi and Da Nang, how deeply the experience had affected her life.

Then she told me of her efforts to locate other women across the country who might be experiencing the problems that she and a dozen of her peers in the Bay Area discovered they shared. They all had experienced difficulty in readjusting to life even after being back from Vietnam for as many as fourteen years.

I was stunned by what Rose told me, yet there was something beyond that, something in her eyes, an intangible, haunting presence that really drew me inthat interview was to determine what I would be doing for the following two years and would lead to the making of this book.

Rose asked me why I was interested in Vietnam veterans. I wasn't really sure myself, but in my explanation I remember speaking of a need to examine my own feelings about the war and maybe reconcile the conflicting emotions that I still carried with me. During the war I was teaching college in the San Francisco area and was constantly aware of the students dilemma in dealing with Vietnam. The young men were facing the draft, and because I had been drafted and sent to Korea when I was their age, I had definite opinions on that subject. I was strongly against our involvement and in sympathy with the people in the antiwar movement, but having been a soldier, I couldn't abandon the people who were going over there. Their lives were on the line, whether or not our government was right in sending them there. I guess you could say, to use a contemporary phrase, I was able to separate the warriors from the war.

Twelve years later I found myself wondering about these people, wanting to hear their stories firsthand. What had it really been like for them in Vietnam? How were they doing today?

Immediately after meeting Rose, I shifted all my efforts into research on women who were in Vietnam. I learned that before 1982 the official estimates had varied from five thousand to fifty-five thousand women in-country, an inconsistency that seemed absurd. The fluctuating figures were due, in part, to the integration of the service records during those years (enlisted men and women became enlisted persons, obscuring the exact number of women). But also, the military has always been guarded in its statistics about women who enter any war zone. In 1983 the official estimates said that seventy-five hundred military women and the same number of civilian women had been in Vietnam during the war years.

I was amazed that fifteen thousand women had been in Vietnam and yet I had heard nothing about them in the aftermath of the war. I think I was typical of the majority of Americans; as the meager file of clippings I had collected indicated, there just had been very little information about the women in any of the media. Why hadn't movies been made about their war, their homecomings? Was it because there were so few of them relative to the male soldiers, or do we actually have a kind of blind spot about the subject? I did a bit of speculation.