Contents

Prelude

We see them as a raven might see

them, from a distance.

The men walk single file, dark strokes etched

against an infinite plain of snow.

Behind them, a days straggling march to the south,

lie a cold prison cell and the grim

accusing faces of the Great Fathers blue-coated soldiers.

Ahead of them, if the spirits prove willing,

are friends and family, and the uncertain

embrace of the Great Mother and her red-coated police.

It is late November 1881, already

the dead of winter.

The men walk with the ghosts of the buffalo.

They are almost ghosts themselves.

The soldiers have taken their rifles and ammunition,

their torn lodges, their moccasins.

They are hungry. The snow stings their skin.

The police: it is hard to tell what the red coats

have taken, are taking. The truth.

Otapanihowin , the means of survival.

Black wings rasp against the frigid air.

Two men stumble, get up, fall.

The leader of the travelers, that Nekaneet

looks up, then looks ahead to the blue smudge

of hills on the horizon. That means, just like

if we walk, if you are ahead, you are

kanikanit, the leader. Nekaneet is walking

north, walking home, walking into another day.

Somewhere up there in the distance,

you and I are waiting, hungry for stories.

{one} Getting There

... conceive a space that is filled with moving, a space of time that is filled always filled with moving...

GERTRUDE STEIN, The Gradual Making of The Making of Americans, 1935

Lets just say that it all began when Keith and I took a trip. Keith is Keith Bell, my companion of going on twenty years, and its largely thanks to his love of travel that Ive seen a bit of the world: the wild-and-woolly moors of Yorkshire, the plains of Tanzania, the barren reaches of Peninsula Valds in Argentina. Yet the journey I want to tell you about was not a grand excursion to some exotic, faraway destination but a trip that brought us closer home. A nothing little ramble to nowheresville.

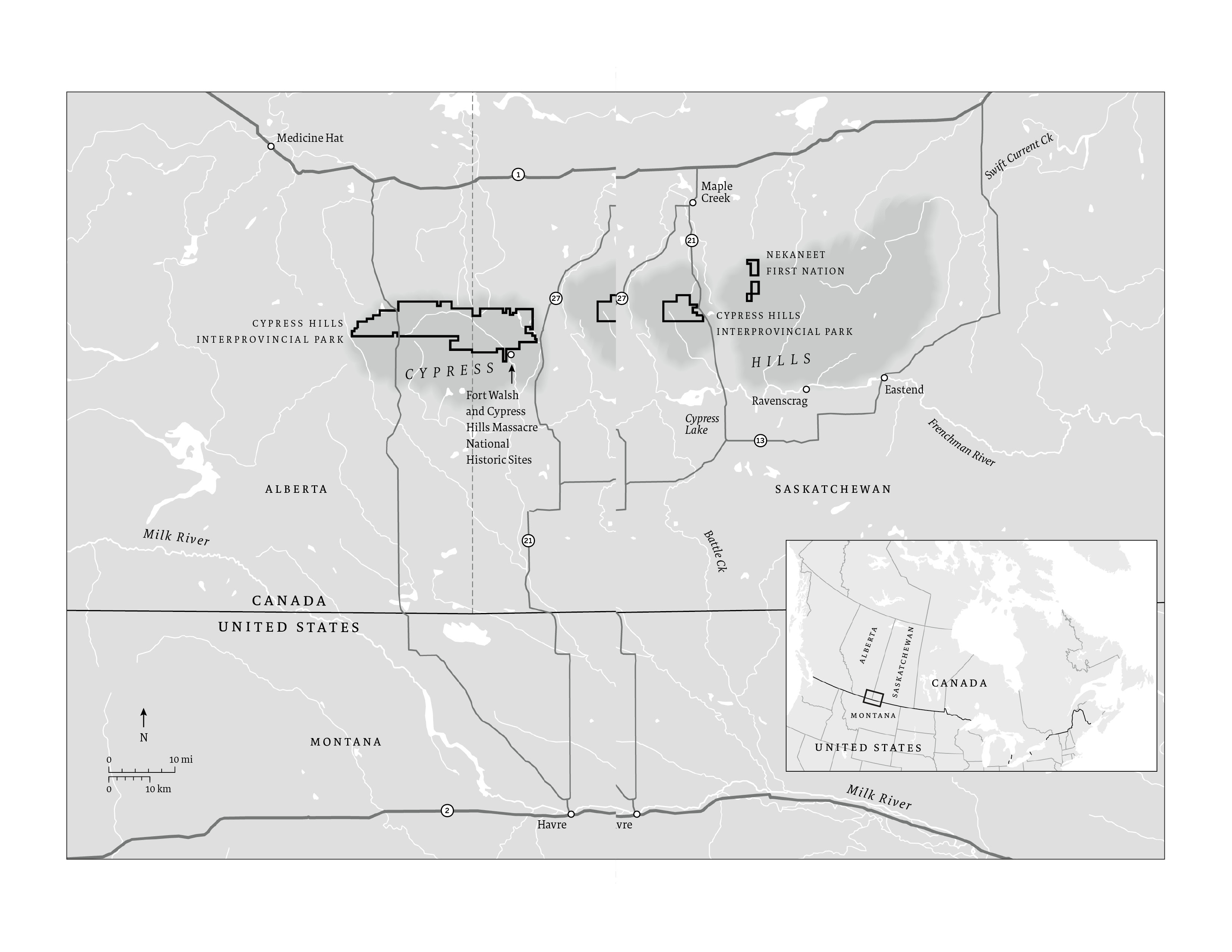

Remember what Thoreau once said about having traveled a good deal in Concord, that insignificant market town in which he was born and mostly lived? In an unintended riff on this Thoreauvian concept, Keith and I find that we have traveled a good deal in and around another insignificant dot on the map, a town called Eastend in our home province of Saskatchewan.

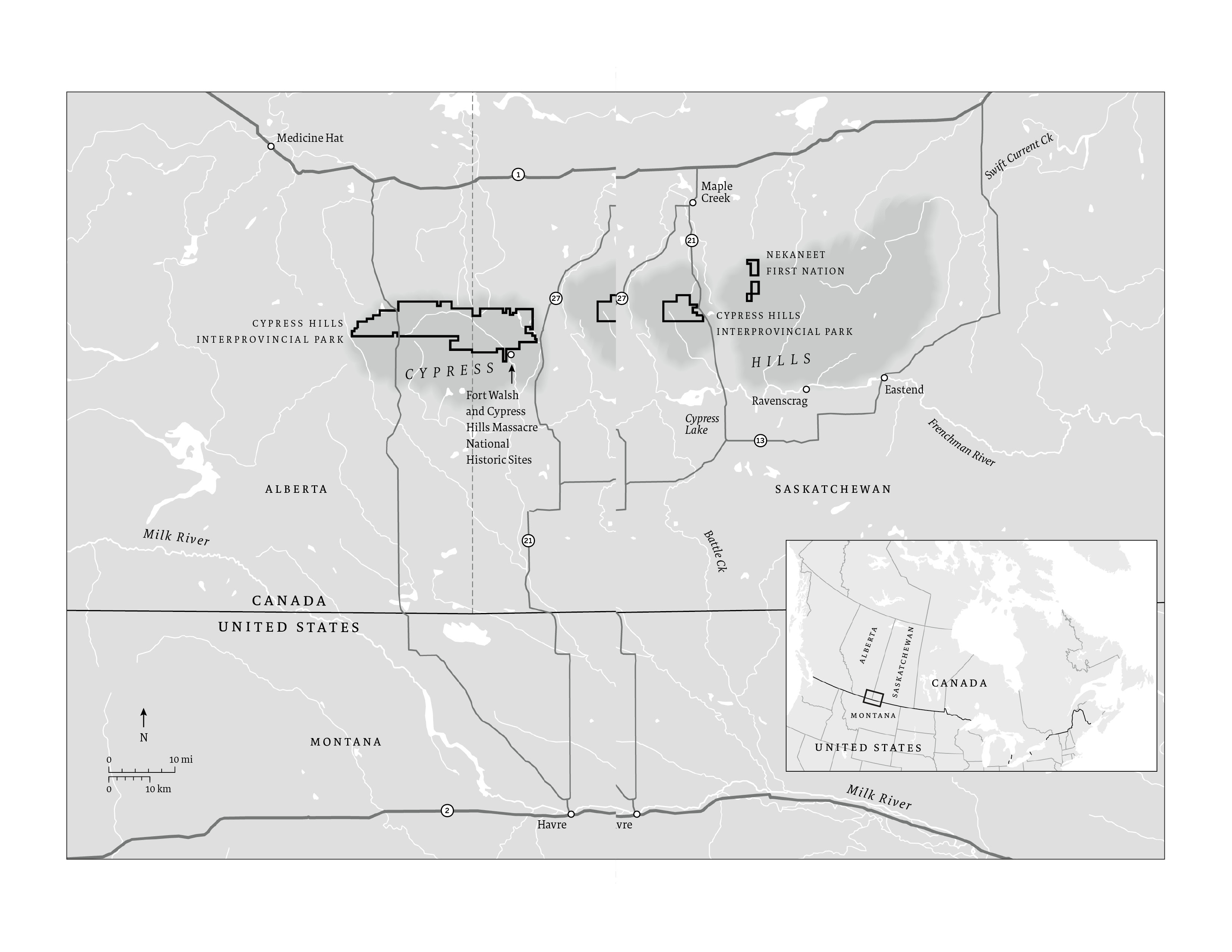

Eastend, population six hundred, lies about a thumbs breadth north of the CanadaU.S. border and more or less equidistant from any place youre likely to have heard of before. Its in the twilight zone where the plains of northern Montana meet and morph into the prairies of southern Saskatchewan, a territory that leaves you fumbling with highway maps. But if you piece the pages together, south to north, east to west, and scribble a rough circle around the centers of populationGreat Falls, Calgary, Saskatoon, Regina, Billings, and back to Great Falls againyoull find Eastend somewhere in the middle, a speck in the Big Empty of the North American outback.

To explain how and why this out-of-the-way place has become so central to our lives, I need to take you back several years, to a day in late September of 2000. Keith was just embarking on a year-long sabbatical leave from his teaching duties as an art historian at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. As for me, I was supposed to be gathering forces to meet the most daunting challenge of my writing career. Earlier that summer, I had thrown common sense to the winds and agreed to prepare a natural history of the whole broad sweep of the western plains, from the Mississippi to the Rockies and from the llanos of Texas north to the wheat fields of Canada. By rights, I should have been at my desk day and night, or in the crypts of the science library, nose to the grindstone. What greater inducement could there be for hitting the open road?

Happily for my guilty conscience, the route we had chosen for our travels that fall led directly into the heart of my research. If I were going to write with authority about grassland ecology (I told myself as I packed my holiday clothes), surely it was my duty to get up close and personal with my subject matter. Im not entirely joking when I say that writing books is my way of getting an education.

And so off we set, Keith and I plus our three trusty canine companionsan aging retriever, a wire-haired dachshund, and a perky young schipperkefrom our home in Saskatoon south under the big skies of Saskatchewan and Montana to our turnaround point, the tourist town of Cody in northwestern Wyoming. From Cody, our return journey would take us north to Eastend, where we planned a brief layover before returning to our obligations in the city.

Cody, Wyoming, is an odd little town, and I am surprised to recollect that this trip marked the second time it had figured into our travel plans. On our earlier visit in the early 1990s, we had stayed in cheap digs along the highway, first at the Western 6 Gun Motel, where neon gunfire flared into the night from a sign at the entranceway, and then at the neighboring Three Bear Motel, where a trio of pathetic stuffed beasts, their mouths set in permanent snarls, stood guard over the check-in counter. This time around, several years older and more inclined to comfort, wed gone upmarket to a respectable, if regrettably staid, establishment with a leafy courtyard.

Funny the things you remember, the things you forget. Even now, when so much else has faded from my mind, I could take you to the exact place we stayed in Cody, show you the room where we slept. See our boxy old blue van angled up to the building, its back doors swung open as we loaded it for the journey home. Hear our voices hanging in the thin morning air.

... binoculars?

... water for the dogs? They say its going to hit ninety.

Any idea what weve done with the maps? (Turns out that where I was headed could not be found on a map, though I had no way of knowing that at the outset.)

Although Codys primary attraction for travelers is its proximity to Yellowstone National Park, an hours drive to the west, the town prefers to see itself as a rootin tootin gateway to the past, to a West not merely of geography but of legend. From June to September, fake gunfighters confront each other in fake gunfights in the wide avenue outside the venerable Irma Hotel (Monday to Friday evenings at six and Saturday afternoons at two). Quite by accident, wed caught them at it one evening, running around with their popguns and braying insults across the deserted street, under the guttering standard of the Stars and Stripes.

In this, as in so much else, the town takes its inspiration from its namesake and founding father, the late William Frederick Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill. As anyone who stops in town quickly becomes aware, Mr. B. Bill was an arresting character. A real-life participant in the conquest of the western plains, he had earned his spurs and his sobriquet in the 1860s when, as a scout for the U.S. Army and supplier to the Kansas Pacific Railway, he is said to have killed 4,860 buffalo in just eighteen months. That works out to about a dozen carcasses every twenty-four hours, assuming that he rested his trigger finger on the Sabbath.

Next page