for John who has given us his heart

Contents

IT WAS MY HUSBAND GRAHAMS idea to buy the houseboat. The notion took shape on the first leg of our move from Illinois to Miami, between pulling away from the cottage in Round Lake and stopping at the county fair outside of Peoria, where we urged our three-year-old, Frankie, into a gargantuan bouncy castle. For a few minutes Frankie seemed to take some pleasure in jumping haphazardly among strangers, until he remembered that he didnt like strangers, and staggered lock-kneed toward the exit. I mention this interlude in the long drive for one reason: a few minutes after we walked away from the enormous cartoonish castle, a gust of wind upended it, bouncing children and all. Ambulances arrived quickly. As we stood among the anxious crowd, I thoughtnot for the first time and not for the lastthat to be a parent is terrifying. Graham once told me how the Stoics practiced imagining their own worst fears had come to pass, to make peace. But it seems to me that what worries us mostpedophiles, kidnappers, dog attacksis least likely to happen, while what is most likely is some unimagined event. And how do we prepare for that?

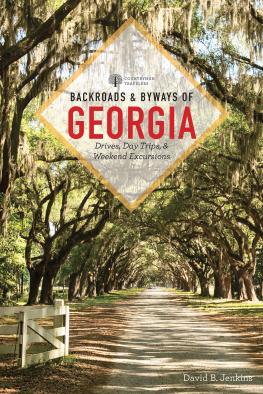

We debated the pros and cons of the houseboat through Tennessee and Georgia. An adventure, Graham said, and relatively inexpensive. Naive, I thought, considering neither of us knew much about boats. Making the most of the locale, he argued. Soggy and mildewed, I said. Wed intended to rent a house on Key Biscayne, near the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, where Graham would occupy a two-year research fellowship. But once my husband latched on to an idea, it was difficult to shake him loose. And the truth was that I wondered if living on a houseboat might be every bit the adventure he hoped. Sometimes you have to remind yourself after adventure comes that there was a time when you went looking for it.

We stopped for fuel outside of Gainesville, and Graham picked up a boat trader magazine, then made a few calls when we stopped again in St. Cloud. By the time we reached Miami, hed found three candidates, all in the Pompano area. After we unloaded the trailer into the spare room of my fathers wifes house, Graham got back on the road with my father at the wheel.

Graham didnt drive, not since he was a teenager. Id done all of the driving from Illinois while he fidgeted in the passenger seat and Frankie slept openmouthed in his car seat, a coloring book open across his thighs and a crayon in his fleshy fist, waking every so often to give the sign for milk and dig into a sleeve of crackers. We stopped every few hours at a rest area, and while I plotted our route and fetched cold drinks, Graham led Frankie in a vigorous game of freeze tag, and they returned to the car red-faced and panting. For much of the ride, I eyed our hulking trailer in the side-view mirror, my gut lurching each time it swerved with the contours of the road. When I started off from a stop, the heavy pull of the trailer reminded me of the lifeguard tests Id taken in junior high, when Id swum the length of a pool wearing two pair of blue jeans and three sweaters. It was exactly the same feeling: I knew where I was going, and I was damned if I wouldnt break away from something powerful to get there.

To the extent that Graham would have admitted that his aversion to driving was a phobia, it was incongruent with his bold and blustery personality, his assertiveness, even his maturity. When wed gotten serious, Id thought I might ingratiate him to the act of driving with subtle, loving encouragement. Hed been in the backseat, sixteen years old, when his mothers car had jumped the median on the way home from a birthday party. It was February; the roads were icy. His sister, Lauren, fourteen at the time and in the passenger seat, was thrown clear and never regained consciousness. Graham insisted that the event had been so sterilized by retelling and scrubbed by time that the two thingswitnessing his sisters death and not drivingwere unrelated. This was a testament not to Grahams lack of self-awareness, I believe, but to the confused nature of each of our personal histories, the mess of contradicting passions and aversions developed over a lifetime. To love ones sister for indulging their mother by singing along on road trips, and to hate ones sister for refusing to wear a seat belt. To love the car trips of ones childhood, the ambling farm roads and lush hillsides, and to hate the heavy inertial machinery of a car, particularly when measured against glass, body, and brain.

GRAHAM CALLED FROM POMPANO. I was drinking a beer in the kitchen while Frankie played with blocks at the table. My fathers wife, Lidia, who was Puerto Rican by birth and spoke perfect English with a heavy accent, stood at the counter, wiping crumbs. Her home was on the Coral Gables waterway, and shed prepared the spare room by piling towels and toys on the bed and clearing dresser drawers. On the nightstand shed set out framed photos of me and my family, including one from Frankies bald and blotchy first weeks. There was one of me and Graham standing on a volcano in Pico, Portugal, and one of my high school portraits, which I hadnt known still existed. The latter called to mind a memory of my mother, whod ordered it mistakenly after Id marked the few that Id not liked. Wed ended up with a stack of glossy photos of me with my eyes in slits, chin pimple glowing, upper lip stuck to my teeth. Id berated my mother soundly. Its disconcerting how often, after a deeply loved person dies, the memories that return are not reverent or nostalgic, but disquieting. My mother was prone to making flighty mistakes, yes, but not until I became a mother did I understand what the flightiness meant: she was overwhelmed at the basic level. More times than I care to admit, Ive come home with the incorrect item from the grocery store. The nonfat instead of low-fat, the vanilla instead of plain. And every time I do, I think of how I ridiculed my mother for doing the same thing, how I rolled my sullen-teenager eyes at her, and how it seems, in retrospect, that she adopted my interpretation of these noneventsthat she was flightyinstead of regarding them the way Ive come to: a parents brain is rarely in one place at a time, and the grocery store does not command ones precious minutes of focus.

I stuffed the portrait into a drawer. Not because the photo was unflattering, but because the memory was.

Lidia handed me the phone. The overspiraled cord pulled annoyingly against my hand. This was exactly the way in which other peoples homes are unlivable, I thought, which led me to the opposite thought: I was grateful to Lidia. I was touched by her efforts. She was generous of time and spirit, eager to be a grandmother to Frankie, and she was not some shiny young thingshe was only a few years younger than my father.

Still, I was relieved when Graham told me on the phone that hed found us a home of our own. It was a 1974 Sumerset, fifty feet in length and fourteen in width, with a propane stove and refrigerator, and a new 30-amp inlet. My father would run shore power and water from the main house, and we could drive the boat to a local marina every few weeks to empty the sewage tanks. The engines and bilge were in good shape, he said. I calculated the square footage in my head: the size of a tiny city apartment.

Shes not pretty, he said, but theres a berth for us and a bunk for Frankie.

I pictured him scraping the stubble of his chin and squinting in the sunlight. I could hear the cries of the gulls in the background, could almost smell the marina, that stew of seaweed and engine oil and fuel. My father had owned boats when I was a child, first a cabin cruiser with a tuna tower that hed shared with two other musicians, then a heavy trawler that took several seconds to respond. I was comfortable riding in boats but had only driven one a handful of times. Id never known my husband, the midwesterner, to use the words bilge and berth .