CAT SENSE

CAT SENSE

How the New Feline Science

Can Make You a Better

Friend to Your Pet

John Bradshaw

BASIC BOOKS

A MEMBER OF THE PERSEUS BOOKS GROUP

New York

Copyright 2013 by John Bradshaw

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, please address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please address the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or email .

Designed by Trish Wilkinson

Set in 11.5 point Goudy Old Style

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bradshaw, John, 1950

Cat sense : how the new feline science can make you a better friend to your pet / John Bradshaw.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-465-04095-7 (e-book) 1. CatsBehavior. 2. CatsPsychology. 3. Human-animal relationships. 4. Cat owners. I. Title.

SF446.5.B725 2013

636.8dc23 2013020749

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

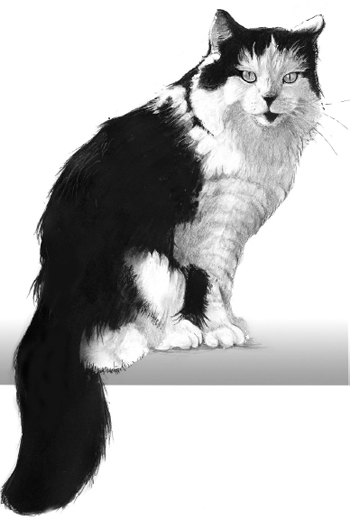

To Splodge

(19882004)

A Real Cat

Contents

Dogs look up to us: cats look down on us.

WINSTON CHURCHILL

When a man loves cats, I am his friend and comrade, without further introduction.

MARK TWAIN

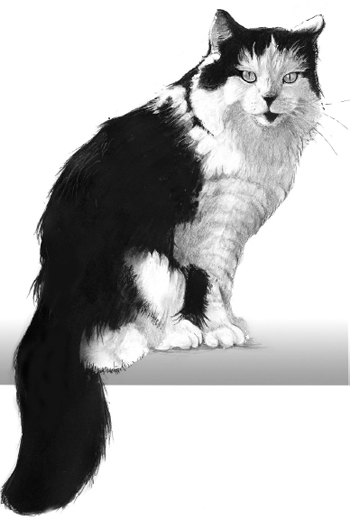

Splodge

W hat is a cat? Cats have intrigued people ever since they first came to live among us. Irish legend has it that a cats eyes are windows enabling us to see into another worldbut what a mysterious world that is! Most pet owners would agree that dogs tend to be open and honest, revealing their intentions to anyone who will pay them attention. Cats, on the other hand, are elusive: we accept them on their terms, but they in turn never quite reveal what those terms might be. Winston Churchill, who referred to his cat Jock as his special assistant, famously once observed of Russian politics, It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key; he might as well have been talking about cats.

Is there a key? Im convinced that there is, and that it can be found in science. Ive shared my home with quite a few catsand have become aware that ownership is not the appropriate term for this relationship. Ive witnessed the birth of several litters of kittens, and nursed my elderly cats through their heartbreaking final declines into senility and ill health. Ive helped with the rescue and relocation of feral cats, animals that literally wanted to bite the hand that fed them. Still, I dont feel that, on its own, my personal involvement with cats has taught me very much about what they are really like. Instead, the work of scientistsfield biologists, archaeologists, developmental biologists, animal psychologists, molecular biologists, and anthrozoologists such as myselfhas provided me with the pieces that, once assembled, begin to reveal the cats true nature. We are still missing some pieces, but the definitive picture is emerging. This is an opportune moment to take stock of what we know, what is still to be discovered, and, most important, how we can use our knowledge to improve cats daily lives.

Getting an idea of what cats are thinking does not detract from the pleasures of owning them. One theory holds that we can enjoy our pets company only through pretending that they are little peoplethat we keep animals merely to project our own thoughts and needs onto them, secure in the knowledge that they cant tell us how far off the mark we are. Taking this viewpoint to its logical conclusion, forcing us to concede that our cats neither understand nor care what we say to them, we might suddenly find that we no longer love them. I do not subscribe to this idea. The human mind is perfectly capable of simultaneously holding two apparently incompatible views about animals, without one canceling the other out. The idea that animals are in some ways like and in others quite unlike humans lies behind the humor of countless cartoons and greetings cards; these simply would not be funny if the two concepts negated each other. In fact, quite the opposite: the more I learn about cats, both through my own studies and through other research, the more I appreciate being able to share my life with them.

Cats have fascinated me since I was a child. We had no cats at home when I was growing up, nor did any of our neighbors. The only cats I knew lived on the farm down the lane, and they werent pets, they were mousers. My brother and I would occasionally catch intriguing glimpses of one of them running from barn to outhouse, but they were busy animals and not over-friendly to people, especially small boys. Once, the farmer showed us a nest of kittens among the hay bales, but he made no special effort to tame them: they were simply his insurance against vermin. At that age, I thought that cats were just another farm animal, like the chickens that pecked around the yard or the cows that were driven back to the barn every evening for milking.

The first pet cat I ever got to know was the polar opposite of these farm cats, a neurotic Burmese by the name of Kelly. Kelly belonged to a friend of my mothers who had bouts of illness, and no neighbor to feed her cat while she was hospitalized. Kelly boarded with us; he could not be let out in case he tried to run back home, he yowled incessantly, he would eat only boiled cod, and he was evidently used to receiving the undivided attention of his besotted owner. While he was with us, he spent most of his time hiding behind the couch, but within a few seconds of the telephone ringing, he would emerge, make sure that my mothers attention was occupied by the person on the other end of the line, and then sink his long Burmese canines deep into her calf. Regular callers became accustomed to the idea that twenty seconds in, the conversation would be interrupted by a scream and then a muttered curse. Understandably, none of us became particularly fond of Kelly, and we were always relieved when it was time for him to head back home.

Not until I had pets of my own did I begin to appreciate the pleasures of living with a normal catthat is to say, a cat that purrs when it is stroked and greets people by rubbing around their legs. These qualities were probably also appreciated by the first people to give houseroom to cats thousands of years ago; such displays of affection are also the hallmark of tamed individuals of the African wildcat, the domestic cats indirect ancestor. The emphasis placed on these qualities has gradually increased over the centuries. While most of todays cat owners value them for their affection above all else, for most of their history, domestic cats have had to earn their keep as controllers of mice and rats.

As my experience with domestic cats grew, so did my appreciation of their utilitarian origins. Splodge, the fluffy black-and-white kitten we bought for our daughter as compensation for having to relocate, quickly grew into a large, shaggy, and rather bad-tempered hunter. Unlike many cats, he was fearless in the face of a rat, even an adult. He soon learned that depositing a rat carcass on our kitchen floor for us to find when we came downstairs for breakfast was not appreciated, and after that he kept his predatory activities privatewithout, I suspect, giving the rats themselves any respite.

Next page