COTTON TENANTS: THREE FAMILIES

Text 2013 The James Agee Trust

Photographs by Walker Evans are reprinted from the the two-volume album Photographs of Cotton Sharecropper Families, held by the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

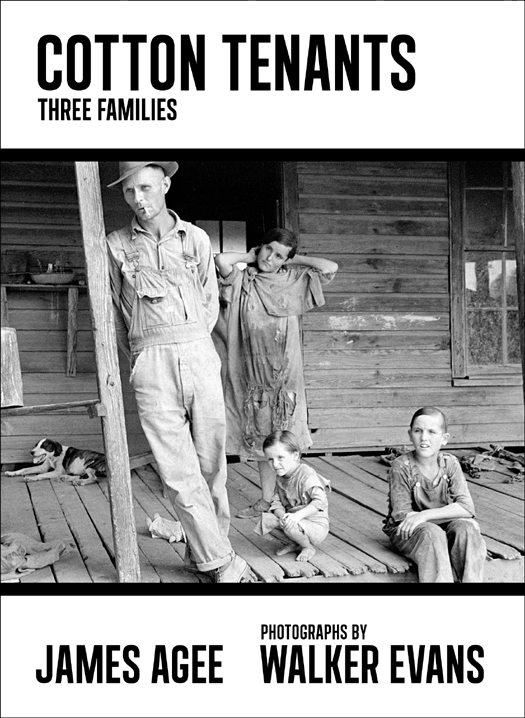

Cover photograph: Walker Evans, Floyd Burroughs and Tingle Children,

Hale County, Alabama, 1936. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

| Melville House Publishing | 8 Blackstock Mews |

| 145 Plymouth Street | and | Islington |

| Brooklyn, NY 11201 | London N4 2BT |

mhpbooks.com

eISBN: 978-1-61219-213-0

A catalog record for this title is available from the Library of Congress.

v3.1

Despair so far invading every tissue has destroyed in these the hidden seats of the desire and of the intelligence.

W. H. Auden

CONTENTS

Editors Note

by John Summers

A Poets Brief

by Adam Haslett

Editors Note

James Agee never lacked for recognition as a poet, film critic, or screenwriter. So much more was expected of him, though. He couldnt shake the suspicion that his talent was wasted even before his health wound down. Nothing much to report, he wrote in a May 11, 1955, letter. I feel, in general, as if I were dying: a terrible slowing-down, in all ways, above all in relation to work. When he succumbed five days later, he was forty-five. It would be three more years before his novel A Death in the Family appeared and won its enduring acclaim. It had been a long time since anyone had mentioned his obscure book about tenant farmers in Alabama, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

Cotton Tenants marked Agees first attempt to tell the story of that momentous trip. Commissioned in the summer of 1936, only to be shelved by Fortune magazineAgee was a staff writerthe typescript wasted away in his Greenwich Village home for nearly twenty years, a piercing fragment lodged within a collection of unread manuscripts. But Agees young daughter inherited both the home and the collection, and eventually (in 2003, to be specific) she cleared it out. Two years later, the James Agee Trust transferred the collection to the University of Tennessee Special Collections Library; there, all the papers were cataloged, and Cotton Tenants was discovered among the remains.

Although no date appeared on the typescript, theres no good reason to believe Agee wrote a later draft or that this isnt the one his editors declined to publish. As far as I know, no other versions of Cotton Tenants exist in any archive, public or private. Nor is it possible, then, to know with certainty the story behind the two appendices, On Negroes and Landownersboth placed here exactly as found on the typescript. This pair of notes suggest, however, the gigantic weight of physical and spiritual brutality [the Negro] has borne and is bearing was not far from his closest perceptions.

As soon as I became aware of the existence of the typescript (in 2010, to be specific), I did the only decent thing and asked the Agee Trust for permission to publish part of it in The Baffler. About one-third of Cotton Tenants first appeared in issue 19, which was released in March 2012. A partnership was then struck between The Baffler and Melville House to bring out the complete report, and the result is before you. It is published for the first time herean act of love for the author.

Kelly Burdick, Hugh Davis, Melissa Flashman, Lindsey Gilbert, David Herwaldt, John T. Hill, Eliza LaJoie, Michael Lofaro, Paul Sprecher, Rob Vanderlan, and David Whitford all had a hand in bringing about this publication. The photos and captions in this volume were selected from Walker Evanss two-volume album, Photographs of Cotton Sharecropper Families, held by the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

John Summers, The Baffler

A Poets Brief

ADAM HASLETT

How to attend to suffering and injustice? There is so much of it. If we move through the world with our ears and eyes open, it is all around us. It seems intractable. We need filters to prevent ourselves from being swamped, classifications to remove our experience of the pain of others to a level of endurable abstraction. By the time we become adultsif we become adultsthis adaptation has taken place without our much noticing it. There are friends and family, whose suffering is ineluctable. There are people in the immediate communities, physical and virtual, that we live in whose troubles we see and talk about. And then there is the pain of distant others, people who live in places weve never been, news of whose suffering arrives through the media, if it arrives at all. It comes as sheer blight, implicating us we know not how. This we either attempt to ignore or treat as an issue, an altogether more tractable entity.

Yet some social visionaries and brokenhearted artists, of whom James Agee was one, fail richly to make this adaptation. Their work, in the manner of Jesus strained through Marx, insists that distinctions between the suffering of intimates and the suffering of strangers are an outrage. With strenuous empathy they report or represent the hardship of the poor and the disenfranchised. The result is a kind of morally indignant anthropology. An ethnography delivered from the pulpit. Which more or less describes Cotton Tenants: Three Families, James Agees report on the working conditions of poor white farmers in the Deep South.

Fortune magazine commissioned the report in the summer of 1936, sending Agee and the photographer Walker Evans to Alabama, and then refused to publish it. No firm evidence has ever surfaced to suggest precisely why. One might ask, though, how any minion in Henry Luces magazine empire, which included Time and Life as well as Fortune, could have expected such a thing to be published.

Agee, born in Knoxville in 1909, joined Fortune as a staff writer in 1932, straight out of Harvard, where hed executed a parody of Luces slick, soul-crushing conception of journalism in the Harvard Lampoon, while at the same time getting in his digs on that high-falutin flub-drubbery which is Harvard. He arrived at his office on the fifty-second floor of the Chrysler Building with a reputation as a poet. (Permit Me Voyage, his first book, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets award in 1934.) Luce believed poets and writers could be taught to expand on the subject of business and invested Fortunes pages with an almost cinematic juxtaposition of words and images. The managing editor Ralph Ingersoll assigned the young poet long, intricate stories on the cultural interests of the overlords amid the ongoing Depression.

Agee wrote of the blood sport of cockfighting (a minor and surreptitious pleasure of the rich), the boredom and decay of Roman aristocracy in Mussolinis Italy (there are parties here and parties there but they are mostly neither here nor there), Saratogas summer horse racing gambol, the U.S. Commercial Orchid, and so on. These stories leave no doubt that business journalism can be turned into a kind of literature, or that Agee was keenly talented at the sort of long-form writing thats become all but extinct in our own time. His 1933 story on the Tennessee Valley Authority, his first important assignment, earned him a personal commendation from Luce, who told him it was among the best