PRAISE FOR LETTERS OF JAMES AGEE TO FATHER FLYE

Comparable in importance to Fitzgeralds The Crack-Up and Thomas Wolfes letters as a self portrait of the artist in the modern scene.

THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

A human document of searing honesty and naked beauty.

ATLANTA CONSTITUTION

The stuff of life Extraordinary letters which in their revelation of the hidden springs of genius constitute a major work of art.

PITTSBURG PRESS

Extraordinary letters [James Agee] was what used to be called an original able to think in general terms without making a fool of himself, therein differing from most American creative writers of this century.

DWIGHT MACDONALD

He simply preferred conversation to composition. The private game of translating life into language, or fitting words to things, did not sufficiently fascinate him. His eloquence naturally dispersed itself in spurts of interest and jets of opinion. In these letters, the extended, serious projects he wishes he could get to have about them the grandiose, gassy quality of talk.

JOHN UPDIKE, THE NEW REPUBLIC

From a reading of the letters Agee emerges as a warm human being with a deep commitment to life as a person and as a writer. It is a rewarding experience to make his acquaintance.

KIRKUS REVIEWS

PRAISE FOR JAMES AGEE AND LET US NOW PRAISE FAMOUS MEN

A book of wondersan untamable American classic in the same line as Leaves of Grass and Moby-Dick.

DAVID DENBY, THE NEW YORKER

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is a classic work, an exercise in pure, declarative humanism. It will read true forever.

DAVID SIMON, CREATOR OF THE WIRE

The most realistic and most important moral effort of our American generation.

LIONEL TRILLING

In my opinion, his column is the most remarkable event in American journalism What he says is of such profound interest, expressed with such extraordinary wit and felicity, and so transcends its ostensibleto me, rather unimportantsubject, that his articles belong in that very select classthe music critiques of Berlioz and Shaw are the only other members I knowof newspaper work which has permanent literary value.

W. H. AUDEN

[James Agees] work continues to feel so vital just because it remains so nakedly vulnerable, so provisional, so utterly lacking in that subtle artistic poison of self-confident complacency He honestly does seem something close to the James Dean of American literature.

MICHAEL DIRDA, THE WASHINGTON POST

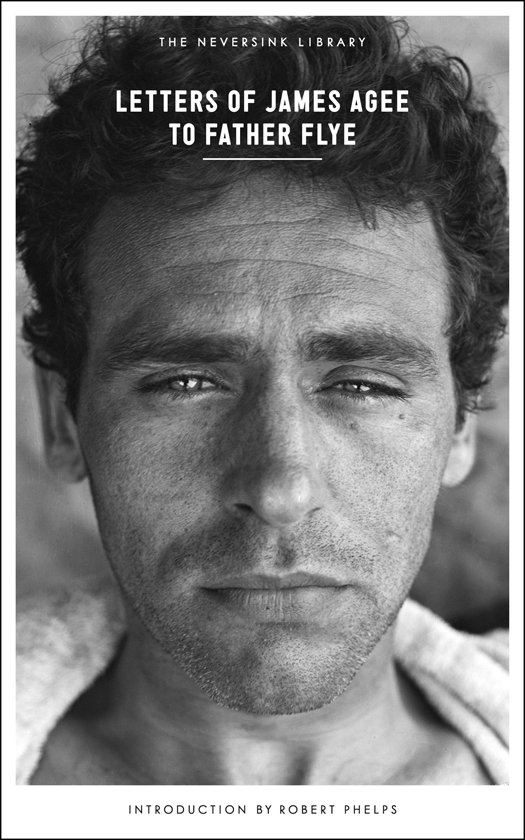

LETTERS OF JAMES AGEE TO FATHER FLYE

JAMES AGEE (19091955) was born in Knoxville, Tennessee. He graduated from Harvard in 1932 and was hired as a staff writer at Henry Luces Fortune magazine. His collection of poetry, Permit Me Voyage, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition and was published in 1934. Though he hoped to dedicate himself full-time to poetry and fiction, Agee would remain a Time, Inc., writer for fourteen years, winning high praise from Luce himself, who considered Agees Fortune essay on the Tennessee Valley Authority to be the best the magazine ever published. (For his part, Agee fantasized about shooting Luce.) His book about Alabama tenant farmers during the Depression, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a collaboration with the photographer Walker Evans, appeared in 1941. The book was a commercial and critical failure, selling just six hundred copies in its first year of publication. Agee was later renowned for his film criticism, which appeared regularly in The Nation and Time. He cowrote the screenplays for The African Queen and The Night of the Hunter, as well as a screenplay for Charlie Chaplin, though it was never produced. Agee died of a heart attack in a New York City taxicab at forty-five. Two years later, his novel, A Death in the Family, was published and won the Pulitzer Prize. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was republished in 1960 and hailed, on its rerelease, as an American classic. In 2013, Cotton Tenants: Three Families, a rediscovered magazine article about the Alabama tenant families, was published to critical acclaim.

JAMES HAROLD FLYE (18841985) was an Episcopal priest and teacher. He spent thirty-six years at St. Andrews school in Tennessee, and later served as a pastor at St. Lukes in New York.

ROBERT PHELPS (19221989) was an editor, author, and translator. He was a cofounder of Grove Press and edited works by Colette and Jean Cocteau.

THE NEVERSINK LIBRARY

I was by no means the only reader of books on board the Neversink. Several other sailors were diligent readers, though their studies did not lie in the way of belles-lettres. Their favourite authors were such as you may find at the book-stalls around Fulton Market; they were slightly physiological in their nature. My book experiences on board of the frigate proved an example of a fact which every book-lover must have experienced before me, namely, that though public libraries have an imposing air, and doubtless contain invaluable volumes, yet, somehow, the books that prove most agreeable, grateful, and companionable, are those we pick up by chance here and there; those which seem put into our hands by Providence; those which pretend to little, but abound in much. HERMAN MELVILLE, WHITE JACKET

ON JAMES AGEE

BY ROBERT PHELPS

A writer first and foremosta born, sovereign prince of the English languageJames Agee was also a prodigal and unself-preserving man, who imparted his extraordinary gifts to many forms, from verse to novels, film scripts to book reviews, friendship to marriage; who, at thirty-two, published a 450-page prose lyric called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men which is at the same time one of the most vulnerable perversities and surest glories of American literature; and who, at forty-five, died leaving a new novel on his desk, a film script in progress, committals as a man and a poet on every side, and as this first volume of his correspondence now makes clear, a thirty-year backlog of some of the most committed letters ever written.

By committed, I mean inhabited. In every one of these letters a human being is present: not just his beliefs and notions and moods, but something containing all these elements, that elusive essence of a complex personality which it usually takes a good novelist to purvey. Most writers leave letters, but only those of a fairly small number can be read, as Agees can, by people not necessarily interested in the writers other works. It seems to require a special gift in addition to the usual literary onesthe gift of being able to give oneself freely, or to cast ones bread on the waters. Some very eminent literary masters have lacked it. Keats had it, and in his own way, so did Henry James. But think of Joyces letterstrivial and wooden; or Rilkes, or Gides, so studied; or even Yeatss, interesting but very cold. In even the most youthful of these letters of Agee, there is the warmth and rhythm of a living man, his tone, his pulse, the color of his soul, and probably the greatest gratification in reading them will come simply from making his acquaintance.