The fifth book in the Kathleen Mallory series, 1999

Dianne Burke of Search and Rescue Research Ltd. Tempe, Arizona.

Peter Gill, Peerless Handcuff Company, Springfield, Massachusetts.

Law Enforcement Equipment Company, Kansas City, Missouri.

Special thanks for the inspiration of an unknown Polish artist, who created a political poster with the legend War, what a woman you are. I saw it many years ago and could never forget it. If I ever track this artist down, the name will appear in subsequent editions.

This book is dedicated to a generation and an era of jazz babies and cigarette smoke, Nebraska farmboys in Paris, women in uniforms and women in sequins, bombs bursting in air, Gershwin tunes and Billie Holiday, rows upon rows of gravestones all over the earth, the cities that fell and the people who prevailed.

The old man kept pace with him, then ran ahead in a sudden burst of energy and fear as if he loved Louisa more. Man and boy raced toward the scream, a long high note, a shriek without pause for breath, inhuman in its constancy.

Malakhais entire body awoke in violent spasms of flailing arms and churning legs, running naked into the real and solid world of his bed and its tangle of damp sheets. Rising quickly in the dark, he knocked over a small table, sending a clock to the floor, shattering its glass face and killing the alarm.

Cold air rushed across his bare feet to push open the door. By the light of a wall sconce in the outer hallway, he cast a shadow on the bedroom floor and revolved in a slow turn, not recognizing any of the furnishings. A long black robe lay across the arms of a chair. Shivering, he picked up the unfamiliar garment and pulled it across his shoulders like a cape.

A window sash had been raised a crack. White curtains ghosted inward, and drops from a rain gutter made small wet explosions on the sill. His head jerked up. A black fly was screaming in circles around a chandelier of dark electric candles.

Malakhai bolted through the doorway and down a corridor of closed rooms, the long robe flying out behind him. This narrow passage opened onto a parlor of gracious proportions and bright light. There were too many textures and colors. He could only absorb them as bits of a mosaic: the pattern of the tin ceiling, forest-green walls, book spines, veins of marble, carved scrolls of mahogany and swatches of brocade.

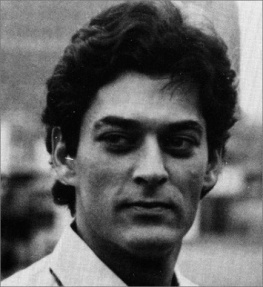

He caught the slight movement of a head turning in the mirror over the mantelpiece. His right arm was slowly rising to shield his eyes from the impossible. And now he was staring at the wrinkled flesh across the back of his raised hand, the enlarged veins and brown liver spots.

He drew the robe close about him as a thin silk protection against more confusion. Awakenings were always cruel.

How much of his life had been stripped away, killed in the tissues of his brain? And how much disorientation was only the temporary companion of a recent stroke? Malakhai pulled aside a velvet drape to look through the window. He had not yet fixed the day or even the year, but only gleaned that it was night and very late in life.

The alarm clock by his bed had been set for some event. Without assistance from anyone, he must recall what it was. Asking for help was akin to soiling himself in public.

Working his way from nineteen years old toward a place well beyond middle age, he moved closer to the mirror, the better to assess the damage. His thick mane of hair had grown white. The flesh was firm, but marked with lines of an interesting life and a long one. Only his eyes were curiously unchanged, still dark gunmetal blue.

The plush material of the rug was soft beneath his bare feet. Its woven colors were vivid, though the fringes showed extreme age. He recalled purchasing this carpet from a dealer in antiquities. The rosewood butlers table had come from the same shop. It was laid with a silver tray and an array of leaded crystal. More at home now in this aged incarnation, Malakhai lifted the decanter and poured out a glass of Spanish sherry.

Two armchairs faced the television set. Of course one for the living and one for the dead. Well, that was normal enough, for he was well past the year when his wife had died.

The enormous size of the television screen was the best clue to the current decade. By tricks of illness and memory, he had begun his flight through this suite of rooms in the 1940s, and now he settled down in a well-padded chair near the end of the twentieth century, a time traveler catching his breath and seeking compass points. He was not in France anymore. This was the west wing of a private hospital in the northern corner of New York State, and soon he would remember why the clock had sounded an alarm.

A remote control device lay on the arm of his chair, and a red light glowed below the dark glass screen. He depressed the play button, and the television set came to life in a sudden brightness of moving pictures and a loud barking voice. Malakhai cut off the volume.

Something important was about to happen, but what? His hand clenched in frustration, and drops of sherry spilled from his glass.

She was beside him now, reaching into his mind and flooding it with warmth, touching his thoughts with perfect understanding. A second glass sat on a small cocktail table before her own chair, a taste of sherry for Louisa still thirsty after all those years in the cold ground.

On the large screen, a troupe of old men in tuxedos were doffing top hats for the camera. Looming behind them was the old band shell in Central Park. Its high stone arch was flanked by elegant cornices and columns of the early 1900s. Hexagonal patterns on the concave wall echoed the shape of the plazas paving stones, where a standing audience was herded behind velvet ropes. Above the heads of the old magicians, a rippling banner spanned the upper portion of the shell, bright red letters declaring the upcoming Holidays of Magic in Manhattan.

The previewof course.

So this was the month of November, and in another week, Thanksgiving Day would be followed by a festival of magicians, retired performers of the past alongside the present flash-and-dazzle generation. Beneath the image of a reporter with a microphone, a moving band of type traveled across the width of the screen to tell him that this was a live performance with no trick photography. The cameras would not cut away.

Malakhai smiled. The television was promising not to deceive the viewers, though misdirection was the heart of magic.

The plaza must be well lit, for the scene was bright as day. The raised stone floor of the band shell was dominated by a large box of dark wood, nine feet square. Malakhai knew the precise dimensions; many years ago, he had lent a hand to build the original apparatus, and this was a close replica. Thirteen shallow stairs led to the top of the platform. At the sides of the broad base step, two pairs of pedestals were bolted into the wood and topped with crossbows angling upward toward a target of black and white concentric ovals. The camera did not see the pins that suspended the target between the tall posts, and so it seemed to float above the small wooden stage.

Memory had nearly achieved parity with the moment. Oliver Tree was about to make a comeback for a career that never was. Malakhai leaned toward Louisas empty chair. Can you find our Oliver in that lineup of old men? He pointed to the smallest figure in the group, an old man with the bright look of a boy allowed to stay up late in the company of grown-ups. The scalp and beard were clipped so short, Oliver appeared to be coated with white fur like an aged teddy bear.

Next page