Janet Fitch

THE REVOLUTION OF MARINA M.

I, like a river,

Have been diverted by the ruthless era.

My life was switched. It flows

Into another channel, past strange lands,

And I no longer recognize my shores.

Anna Akhmatova,

Northern Elegies

New Years 1932, Carmel-by-the-Sea

ROCKING ON THE RAZOR-MUSSELED bay, lulled by the sleepy toll of buoy bells, the music of rigging, the eloquent stanzas of the waves, I wait for news from the sea. No boys and girls play on the deserted beach now, only a few stoic fishermen huddle on upturned buckets. The slow labor of the poet building himself a stone house at the coves south end makes for mild entertainment. If I knew him better Id tell him the danger of trusting to solid things. Its an illusion. All one needs is a rented cabin, a decent stove, a small boat, a garden gone to seed for winter. I watch the lanky form of my landlords son crossing the shingle, coat collar up, stopping by to collect rents. I have the money in a cigar box back in my cabin, most of it anyway. Its only five dollars, the shacks not built for winter. I dont complain, there are shutters to block out a storm, and an iron stove with a solid pipe. In a few minutes, I will beach my boat on the pebbly shore and give him his duewell share a bottle of homebrew, or perhaps he comes with a flask. No liquor on the premises just nowthough it will come soon, down from San Francisco. Those who love poetry, even my unreadable foreign brand, are a tender breed. Why dont you write in English, Marina? asks my friend Elizabeth. You speak it so well.

My dilemma. My English is good enough for the little stories I publish in pulp magazines, but for poetry one needs ones native tongue. The voice of the soul is not so easily translated. Though to say soul here is already wrong. We say dusha, meaning not just the spiritual entity but also the person himself.

A tug on the line. I pull in a shining perch, shockingly alive. I add it to a rockfish in my pail and row back to shore. I have a motor but spare the gas when I can. At times like this I surprise myself, how Ive managed to create something of a life on this foggy shore out of the broken pieces of myself, scavenged from the sea like flotsam. Or is it jetsam it irks me not to know the difference. I will have to consult my oracle, the giant moldy Websters Ive acquired since my arrival here, the very edition we had in my childhood home that lived on a stout shelf along with the Nouveau Larousse Illustr, the Deutsches Wrterbuch, and Dahls Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language. When I was very small, I had to sit on my knees to read these great books. Why do you not write in English, Marina? Because when you are flotsam, or jetsam, you cling to what is yours.

After the landlords lanky son leavesa roll in the hay, that delightful imageI lay my Websters on the scrubbed table in the lantern light, to learn that flotsam is the debris left from shipwreck, while jetsam is merchandise thrown overboard from a ship in crisis to lighten the load. Ship in crisis. That it was. The difference seems to be tied to the fate of the ship. Did it survive after shedding those such as myself, tossing us overboardjetsamto lighten the load, or did it founder, to be torn apart, mastless and rudderless, the planks and boards washed ashoreflotsamperhaps one bearing the ships name. And the name was Revolution.

I can hear her half a mile off, Elizabeth in her clattering jalopy. Ive made cornbread in my iron pot, a Dutch oven always the Dutch, showing up in surprising places. I will have to look that up. I dredge the pink-gilled perch in cornmeal and fry it with a hunk of salt pork. My mouth stirs these tasty ks, the t, the phunk of salt pork. My friend has brought a crate of artichokes down from Salinas and Polish vodkaSmirnoff. Where did she find it? The Americans prefer their native bourbons and ryes. Such a blessing after all these years of bathtub hooch. Her company is so sweetthis lovely girl with lines to grace the hood of a luxury car. Yet she treats me as if I were the exotic oneher movements careful and calm. What have I done to deserve to be treated so tenderly? Am I so dikayawildthat I might startle and take flight like a red deer?

After dinner, she showers me with gifts, H.D.s Red Roses for Bronze and the new Wallace Stevens, books she, a student of literature at the university at Berkeley, can ill afford. And now shes hiding something else behind her back, her hazel-gold eyes bright, anticipatory. I pour more vodka into our jelly-jar glasses and pretend not to notice. Finally, she holds it out, a gift wrapped in a sheet of the San Francisco paper. I flex itthin, paperboundand try to guess. A layer cake? A phonograph? Then tear open the wrapper.

Russian. Kem byt? A book for childrenWho Will I Become? by Vladimir Mayakovsky. My heart catches in my throat like fingers in a slammed door. Mayakovsky, dead two years now. Dead by his own hand. Or maybe not. You never know. But dead just the same.

Do you know it? she asks, eager to have surprised me.

I shake my head, remembering the last time I saw him, in Petrograd at the House of Arts, a robust and charismatic man, full of swagger. Who Will I Become? Inside, the same stepped verse he came to favor. This is the ship that sailed on without me: 1928, Government Press. And here are the childs choices: doctor, worker, auto mechanic, pilot, streetcar conductor, engineer. But no Chekist. No apparatchik. And nowhere a poet. Nowhere a cloud in trousers.

I get very drunk that night in the little cabin and recite aloud everything I know penned by Vladimir Vladimirovich. I sing it as he did, that thrilling bass voice, booming like the waves, so Elizabeth can hear the music. When I run out of his poems, I move on to Khlebnikov, Chernikov, Kuriakin. My pretty friend cannot believe how many lines I know by heart, but this is nothing. Theres no end to the flow once the gate is opened. Here they teach children to think, but they dont train the memory. I suppose they cannot imagine what a person might be called upon to endure, when a line of poetry can mean the difference between strength and despair. I drip candle wax into my glass, watch the drops swirl and adhere. What are you doing? she asks.

Its something we used to do, to tell our fortunes. I recite for her:

On St. Basils Eve, cast the wax in water.

At midnight cast the wax.

Sing the songs the girls have sung

Since ancient times.

Prepare, my dear,

If you dare, my dear,

To see your future.

Part I

The Pouring of the Wax

(January 1916February 1917)

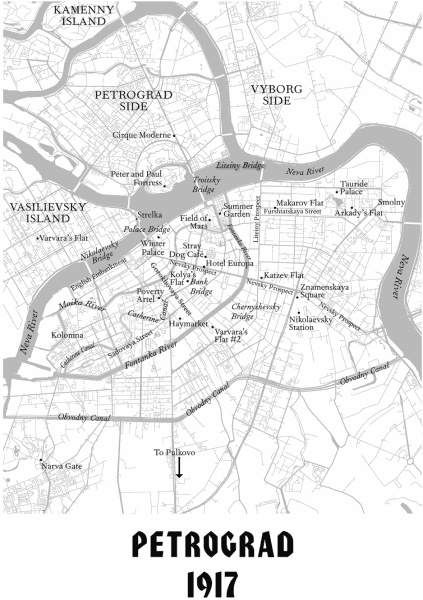

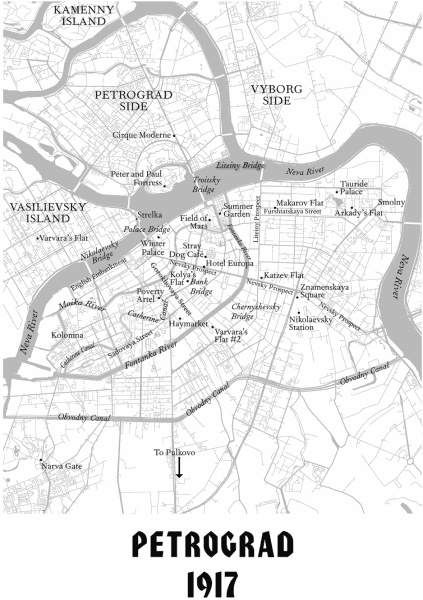

MIDNIGHT, NEW YEARS EVE, three young witches gathered in the city that was once St. Petersburg. Though that silver sound, Petersburg, had been erased, and how oddly the new one struck our ears: Petrograd. A sound like bronze. Like horseshoes on stone, hammer on anvil, thunder in the namePetrograd. No longer Petersburg of the bells and water, that city of mirrors, of transparent twilights, Tchaikovsky ballets, and Pushkins genius. Its name had been changed by warPetersburg