ALSO BY DAVID FINKEL

The Good Soldiers

Copyright 2013 David Finkel

Foreword copyright 2013 Lieutenant-General Romo Dallaire

Introduction copyright 2013 Carol Off

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisheror in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

Photograph on by Shawnee Lynn Hoffman, courtesy of Shawnee Lynn Hoffman. All other photographs courtesy of the author.

first appeared, in slightly different form, in The New Yorker.

Excerpt from The Iliad by Homer, translation by Richard Lattimore. Copyright 1951 and 2011 by University of Chicago Press. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

Bond Street Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House of Canada Limited

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Finkel, David, 1955-, author

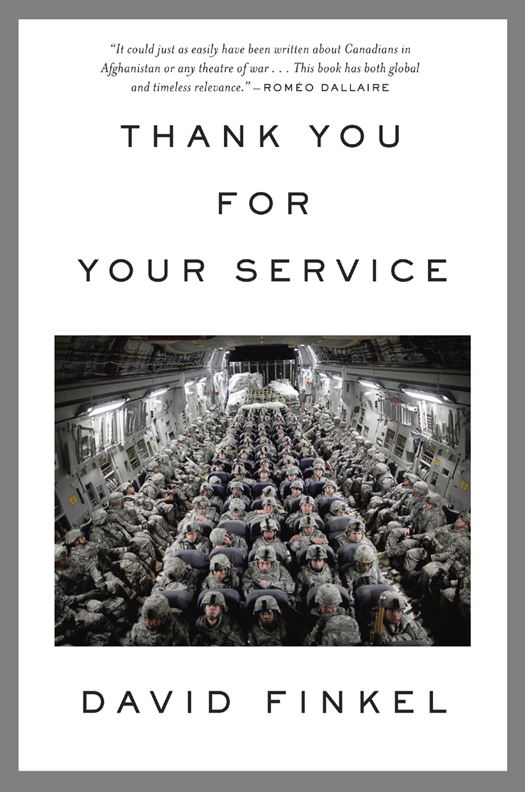

Thank you for your service / David Finkel.

eISBN: 978-0-385-68097-4

1. SoldiersUnited StatesBiography. 2. Post-traumatic stress disorderPatientsBiography. 3. Iraq War, 2003-2011VeteransUnited StatesBiography. 4. United States. ArmyMilitary lifeHistory21st century. I. Title.

DS79.764.U6F57 2013 956.70443 C2013-902643-6

C2013-903028-X

Jacket design by Darren Haggar

Jacket photograph by Damon Winter /The New York Times / Redux

Published in Canada by Bond Street Books, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company

www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

For Phyllis Beekman,

who taught me about damage and recovery

To Elizabeth Helen Hill

for saying okay

Contents

FOREWORD

by Lieutenant-General Romo Dallaire

War is persistent and universal, and so too is the terrible physical and psychological price paid by the men and women who fight it, and their families. David Finkel has demonstrated an exceptional ability to identify and describe the psychological consequences of modern warfare.

Although Thank You for Your Service, like Finkels earlier book, The Good Soldiers, focuses on men from a U.S. Army infantry battalion that served in Baghdad, it could just as easily have been written about Canadians in Afghanistan, or any theatre of war, for that matter. This book has both global and timeless relevance. In the eloquence of the soldier-speak captured by Finkel, all wars are the same, only the landscape changes.

Finkel shows us, from an intimate vantage point, the damage done to soldiers, their families and those that command them, and he clarifies how, in military culture, the very concept of a mental injury carries a great deal of stigma. This book is both difficult to read and rewarding. It calls up the full range of emotions: tears at the plight of a young family struggling with the baggage of war, anger at the shortage of therapeutic help for the injured and their resulting overreliance on medication, and even occasionally laughter at the unique humour soldiers use to mask their emotions.

Finkel does find some signs of hope. He depicts the unflagging courage and determination of the injured, and the strong desire on the part of a number of senior generals to overcome the mental health challenges of modern warfare. Most encouragingly, he sees signs of success in some of the many programs that now exist for the returning injured. And their predecessors from earlier wars? As Finkel writes, Most of them came home from their wars to no help at all.

INTRODUCTION

by Carol Off

A different person came home. Thats a lament Ive heard so many times. A husband or wife, a son or a daughter went off as a soldier to Afghanistan or Bosnia or Rwanda but never really returned. Oh, they came back physicallythey even looked the same after the tour in Medak or Sarajevo or Kandaharbut they were fundamentally altered. And never in a good way.

How is it possible? How can decades of a persons development become rewired in a matter of six months or a year? A relatively happy and well adjusted man or woman comes back from a military mission morose and withdrawn. A solid, loving father and husband becomes a monster, capable of abuse and violence. A dependable, mood-steady warrior returns sullen and paranoid, and soon after hangs himself or smashes his car into a brick wall. What happened over there to change everything?

Thank You for Your Service is a journey into the lives of those who returned to the United States from war in Iraq but could no longer fit into the space that they had occupied before deployment. The men of U.S. 2-16 Infantry Battalion who David Finkel follows so intimately are angry, disengaged and frightened of themselves and others. Wives do not recognize these men, and eventually the women run out of patience and love, or they are forced to flee the violence and chaos that now surrounds the man they married. Then there are the soldiers who simply give up trying to make sense of it all and take their own lives, leaving partners, parents and children bewildered.

The majority of post-deployment soldiers in the United States and Canada do not report the psychological problems described as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or, in military language, Operational Stress Injuries. But no countrys defence department is really keeping an adequate score. One Canadian military analysis claims that 13 per cent of our troops suffered from mental and emotional problems within five years of returning from Afghanistan. But that doesnt begin to tell the story. Soldiers are reluctant to disclose their mental health issues, fearing reprisal or mockery, and governments are loath to gather full statistics out of a concern for the costs of compensation.

Many stress injuries are explained as the obvious consequences of extreme violence. Soldiers get bashed around when their armoured carriers are ambushed and, if the men and women inside survive, their brains are often bruised. They sustain concussions in everything from combat to car accidents. They also see colleagues blown up, and then must overcome their fear in order to return to duty the next day. Given the ordeals, it is surprising that there arent more stress injuries. But the Canadian experience with PTSD poses more troubling and complex questions about the origins of these injuries. Why do so many soldiers suffer PTSD when they return from so-called peacekeeping missions?

Throughout the 1990s, an unprecedented number of Canadian Forces personnel headed off to United Nationssponsored missions, principally in Africa and the former Yugoslavia. Many soldiers came back severely traumatized. Canadians were led to believe that these missions were benign and friendly and included no combat role, but the troops who took part in the operations discovered that there was often no peace to keep. They were under orders to maintain the UN mandate of neutrality in the midst of ethnic cleansing and genocide. Some Canadian units disobeyed the higher command in order to intervene, notably in Croatia and Rwanda. Here was their dilemma: How can a soldier, well armed and well trained, simply observe while women are raped, children murdered and whole families driven from burned and looted homes?