Copyright 2014 by Irving Finkel

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company. Originally published in Great Britain by Hodder & Stoughton, a Hachette UK Company, London. This edition published by arrangement with Hodder & Stoughton.

www.nanatalese.com

Doubleday is a registered trademark of Random House LLC. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House LLC.

A portion of this work first appeared in the Daily Telegraph, London (January 2014).

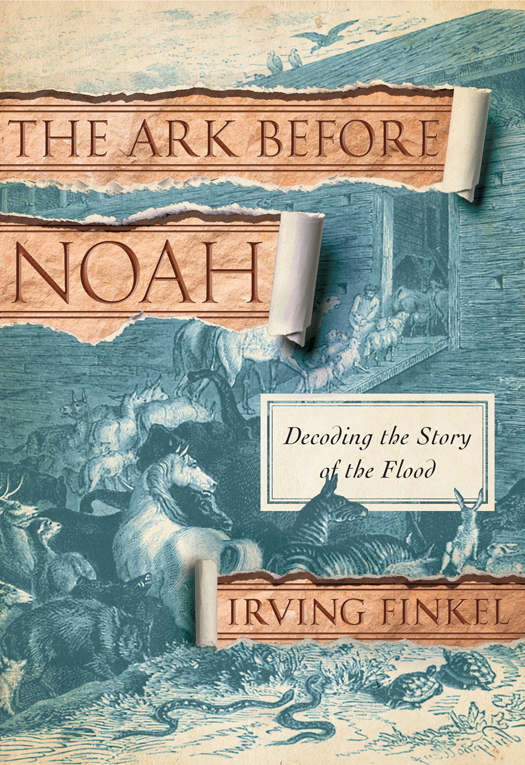

Jacket design by Michael J. Windsor

Jacket photograph Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-385-53711-7 (hardcover)ISBN 978-0-385-53712-4 (eBook)

v3.1

This book is dedicated, in respectful admiration, to Sir David Attenborough

Our own Noah

(

Contents

1

About this Book

Times wheel runs back or stops:

Potter and clay endure

Robert Browning

In the year AD 1872 one George Smith (184076), a former banknote engraver turned assistant in the British Museum, astounded the world by discovering the story of the Flood much the same as that in the Book of Genesis inscribed on a cuneiform tablet made of clay that had recently been excavated at far-distant Nineveh. Human behaviour, according to this new discovery, prompted the gods of Babylon to wipe out mankind through death by water, and, as in the Bible, the survival of all living things was effected at the last minute by a single man. He was to build an ark to house one male and one female of all species until the waters subsided and the world could go back to normal.

For George Smith himself the discovery was, quite plainly, staggering, and it propelled him from back-room cuneiform boffin to, eventually, worldwide fame. Much arduous scholarly labour had preceded Smiths extraordinary triumph, mind you, for his beginnings were humble. Endless months of staring into the glass cases that housed the inscriptions in the gallery resulted in Smith being noticed, and eventually he was taken on as a repairer in the British Museum in about 1863. The young George exhibited an outstanding flair for identifying joins among the broken fragments of tablets and a positive genius for understanding cuneiform inscriptions; there can be no doubt that he was one of Assyriologys most gifted scholars. As his abilities increased he was made Assistant to the famous Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, and put to sorting the thousands of clay tablets and fragments that had by then entered the Museum. Sir Henry (181095) had played an important and adventurous role in the early days of Assyriology and by this time was in charge of the cuneiform publications put out by the Trustees of the British Museum. Smith called one of his working categories Mythological tablets and, as the pile of identified material grew, he was slowly able to join fragment to fragment and piece to larger piece, gradually gaining insight into their literary content. The Flood Story that he came upon in this way proved to be but one episode within the longer narrative of the life and times of the hero Gilgamesh, whose name Smith suggested (as a reluctant makeshift) might be pronounced Izdubar.

George Smith thus set under way the cosmic cuneiform jigsaw puzzle that is still in heroic progress today among those who work on the British Museums tablet collections. A problem that confronted him then as it sometimes confronts others today was that certain pieces of tablet were encrusted with a hard deposit that made reading the signs impossible. It so happened that one substantial piece which he knew was central to the Izdubar story was partly covered with a thick, lime-like deposit that could not be removed without expert help. The Museum generally had Robert Ready standing by, a pioneer archaeological conservator who could usually work miracles, but he happened to be away for some weeks. One can only sympathise with the effect this had on George Smith, as recorded by E. A. Wallis Budge, later Keeper of Smiths department at the Museum:

Smith was constitutionally a highly nervous, sensitive man, and his irritation at Readys absence knew no bounds. He thought that the tablet ought to supply a very important part of the legend; and his impatience to verify his theory produced in him an almost incredible state of mental excitement, which grew greater as the days passed. At length Ready returned, and the tablet was given to him to clean. When he saw the large size of the patch of deposit, he said that he would do his best with it, was not, apparently, very sanguine as to results. A few days later, he took back the tablet, which he had succeeded in bringing into the state in which it now is, and gave it to Smith, who was then working with Rawlinson in the room above the Secretarys Office. Smith took the tablet and began to read over the lines which Ready had brought to light; and when he saw that they contained the portion of the legend he had hoped to find there, he said, I am the first man to read that after more than two thousand years of oblivion.

Setting the tablet on the table, he jumped up and rushed about the room in a great state of excitement, and, to the astonishment of those present, began to undress himself!

Smiths dramatic reaction achieved mythological status in itself, to the point that probably all subsequent Assyriologists keep the tactic in reserve just in case they too find something spectacular, although I have often wondered whether Smith might not have suffered an epileptic response to his great shock, for this reaction could be a symptom.

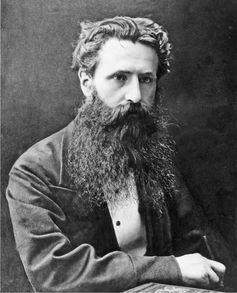

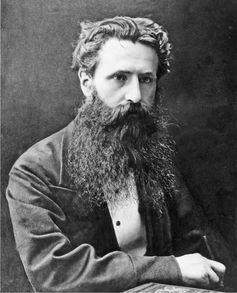

George Smith in 1876 with a copy of his The Chaldean Account of Genesis.

Smith chose a very public platform from which to announce his discoveries: the December 3rd meeting of the Society of Biblical Archaeology in London, 1872. August dignitaries were present, including the Archbishop of Canterbury since the topic had serious implications for church authority and even the classically disposed Prime Minister, W. E. Gladstone. The meeting ended late and in unanimous enthusiasm.

For Smiths audience, as it had been for the man himself, the news was electrifying. In 1872 everyone knew their Bible backwards, and the announcement that the iconic story of the Ark and the Flood existed on a barbaric-looking document of clay in the British Museum that had been dug up somewhere in the East was flatly indigestible. Overnight, the great discovery was in the public domain, and no doubt the Clapham omnibus buzzed with Have you heard about the remarkable discovery at the British Museum?