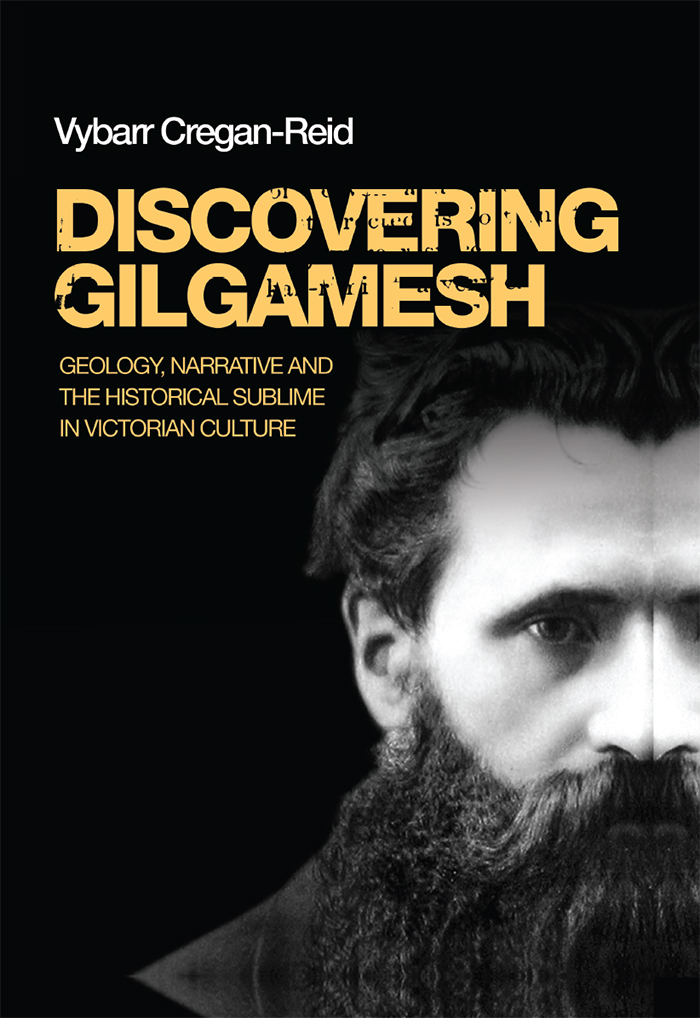

Discovering Gilgamesh

Geology, narrative and the historical sublime in Victorian culture

Vybarr Cregan-Reid

Manchester University Press

Manchester and New York

distributed in the United States exclusively

by Palgrave Macmillan

Copyright Vybarr Cregan-Reid 2013

The right of Vybarr Cregan-Reid to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK

and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

Distributed in the United States exclusively by

Palgrave Macmillan, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York,

NY 10010, USA

Distributed in Canada exclusively by

UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall,

Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for

ISBN 978 0 7190 9051 6 hardback

First published 2013

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset

by Action Publishing Technology Ltd, Gloucester

For Johanna, Rebecca, Erika and John.

Contents

I t is impossible to write a book without accruing numerous debts of gratitude. First among these is due to Adam OFarrell for much kindness, loyalty, enduring good humour, and for keeping a lid on things.

Initial research for this book began with the assistance of the Leverhulme Trust who awarded me an Early Career Fellowship at Sussex University. Since then, my colleagues in the School of English at the University of Kent have been kind enough to grant me research leave to write the bulk of the manuscript. Parts of this book have found their way into print in various forms and I am grateful to their editors for their help (among them Adelene Buckland, Ruth Livesey, and Barry Tharaud) and for permission to reprint. A different version of chapter three appeared as Macaulay and the Historical Sublime; or, Forgetting the Past and the Future in Nineteenth-Century Prose (33:2, 2006, 22554). Preliminary ideas for some of the latter sections of the book appeared in The Gilgamesh Controversy: the Ancient Epic and Late-Victorian Geology, Journal of Victorian Culture (14:2, 2009, 22437).

Writers need numerous readers so I am happy to pay thanks to David Allinson, Jennie Batchelor, Carolyn Burdett, Holly Furneaux, Andrew Hadfield, Caroline Rooney, and Lindsay Smith, all of whom were kind enough to give feedback on various aspects of the book. Rod Edmond, Norman Vance, and Brian Young charitably shared their thoughts on the entire manuscript; advice given by Ralph OConnor was also gratefully received. Sarah Collins, the Assistant Keeper at the British Museums Department of the Middle East, was an invaluable source of information, as was David Damrosch at Harvard; the librarians and staff at the London Library, St Dieniols, the British Library, and the Bodleian also deserve thanks. Special thanks also go to Vernon Duker for his help in permitting access to some vital primary source materials, and to all of the staff at Manchester University Press.

Over the years many other friends and colleagues have tirelessly listened to the Gilgamesh business, among them the best of friends, Huw Bevan and Sandra Cryan, as well as Margaret Cantwell, Jon Cranfield, Gary Hazeldine, Sarah Horgan, Clive Johnson, Andy Kesson, Robert Maidens, Tom Montgomery, Sian Prime, Ruth Robbins, Courtney Salvey, Karen Sayer, Scarlett Thomas, and Lynne Truss. I owe thanks, too, to Alan Jeffers for much encouragement over the years and to Vivienne Schuster at Curtis Brown for trying to find a way. I also find myself carrying a debt that I cannot settle because of the sad death of Mary Dove. Throughout my time at Sussex she always showed a great interest in my work. I wish she were still here to read this so she may know how dearly she is missed.

Finally, thanks to my brother, to my sisters, and to my mother, for whom this book counts as a small instalment of gratitude for their steadfastness and encouragement over the years. This would not have been written without them.

(John Ruskin, Letters, 24 May 1851)

[A] lot of holes tied together with sediment.

(Derek Ager, on deep time, The Nature of the Stratigraphical Record)

The evidence of scholarship is now destroying the inveterate error which has so deeply and injuriously affected the creeds, the legislation, the sympathies, the entire habits of life and thought of the modern world.

(Review of George Smiths Chaldean Account, 11 December 1875)

[I]t is mostly in periods of turmoil and strife and confusion that people care much about history.

(William Morris, News from Nowhere)

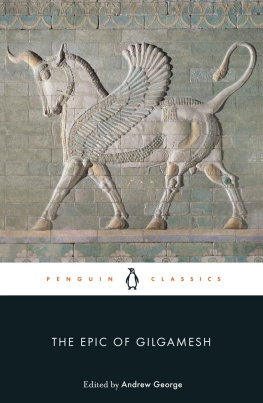

T he rediscovery of the ancient Epic of Gilgamesh in 1872 became the fulcrum for a series of debates about time and history in the Victorian period. The oldest epic excavated from the earth contained stories that had been thought to be original to the Old Testament, but Gilgamesh, it was revealed, was written many centuries before even the earliest parts of the Bible. The manner in which the discovery was reported in the international media and the way in which the stories of King Gilgamesh were later taken up in periodicals, journals, and geological theory are indicative of an anxiety in Victorian culture concerning the status of history. Many critics, commentators, and historians have assumed that the extreme age of the earth was something of a settled matter for the Victorians after around 1830 (with the publication of Charles Lyells Principles of Geology). The time of Gilgameshs rediscovery was also one when interpretations and chronologies of the Bible were again being tested against other forms of historical evidence. And finally, the controversy revisited the centuries-old question of whether there had ever been a global flood with only a few survivors from which we are descended. There are whole series of such debates about the age of the earth, going back to the chronologies of the Venerable Bede, but they take on a certain urgency and considerable loquacious variety in the Enlightenment through to the early/mid-nineteenth century. At the latter point, the once-volcanic debates that had fascinated, rather than simply divided, geognosists, earth physicists, and finally geologists, cooled somewhat. For the savants of the early nineteenth century the age of the earth was believed to consist of aeons of time far beyond the five to six millennia of the most prominent biblical chronologers. For Europe and Americas mid-nineteenth century savants deep time was not really an issue when set against the young-earth model of time; instead, deep time was only something that needed to be titivated and refined by further research.