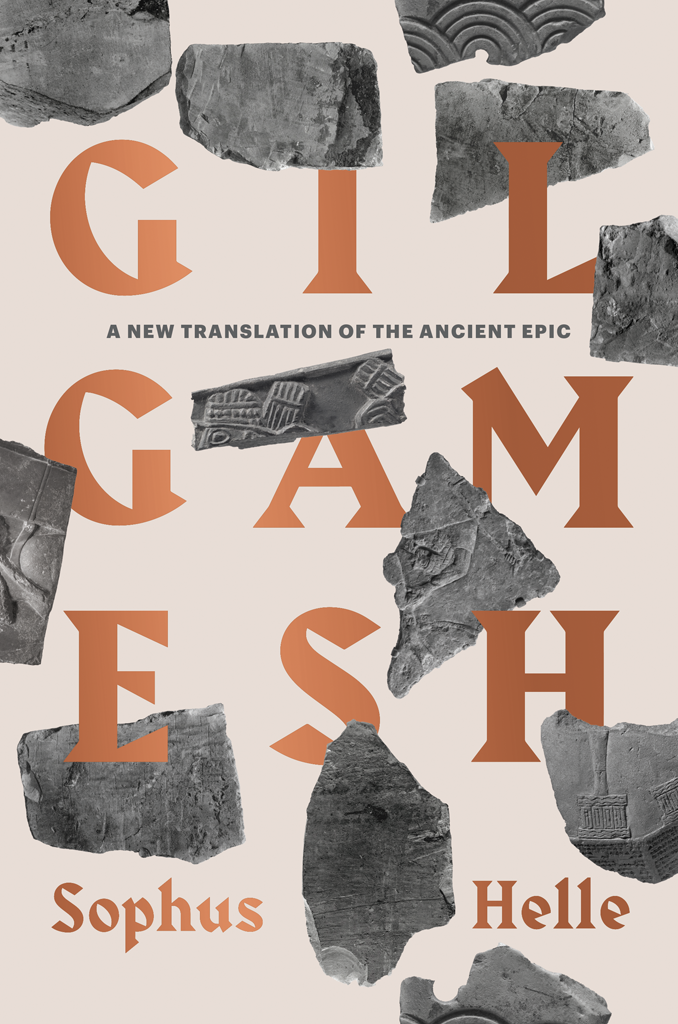

A NEW TRANSLATION OF THE ANCIENT EPIC

GILGAMESH

WITH ESSAYS ON THE POEM, ITS PAST, AND ITS PASSION

SOPHUS HELLE

Yale

UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW HAVEN & LONDON

Published with assistance from the Louis Stern Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2021 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Designed by Dustin Kilgore.

Set in Spectral type by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020949520

ISBN 978-0-300-25118-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Gilgamesh is tremendous! the poet Rainer Maria Rilke exclaimed in 1916. I hold it to be the greatest thing a person can experience. Many modern readers have shared Rilkes enthusiasm for the epic. Gilgamesh will soon celebrate the 150th anniversary of its rediscovery in 1872, and since then the epic has swept like a flood through the literary world, captivating readers across the globe. Printed in millions of copies and translated into two dozen languages, including Klingon, Gilgamesh is an unlikely best seller. Who would have thought that a story written three millennia ago, in the dead language of a long-forgotten culture, could appeal so powerfully to modern readers?

Imagine a novel that came out today being read and appreciated in the year 5120. Our culture will be long gone by then, our digital files corrupted, our paper books crumbled. Will there even be humans in 5120? For a book to survive that long seems almost impossible, but this is the scope of Gilgameshs triumph. Composed around the eleventh century BCE, it has survived three thousand years of history, and may well survive three thousand more.

But Gilgamesh also feels strangely fresh. It reads less like the poetic Methuselah it is and more like its own young, hyperactive hero. One reason why the epic has not been worn down by age is that it reentered the literary world relatively recently, compared to the Greek and Roman classics that have been known and read since they were first composed. Gilgamesh comes to us unburdened by reception, open to new eyes. As the poet Michael Schmidt puts it, It has not had time to sink in. Impossibly ancient as it is, Gilgamesh can still be read as if for the first time.

The secret to Gilgameshs success lies in something else Rilke wrote about it: It concerns me.of fundamental humanity, but it does so in the strangest way possible. The hero is anything but an average human. He is two-thirds god and eighteen feet tall, an ancient despotic tyrant who goes in search of immortality. If Gilgamesh tells us anything about the human condition, he does so by embodying its farthest possible extreme. He is a litmus test for us all: what he cannot do, none of us can hope to, and this makes his failure to become immortal all the more poignant.

Rilke felt that Gilgamesh concerned him because he shared the heros desire for immortality, but every age and every reader finds in the epic a new aspect to connect with. It is an existential struggle against death. It is a romance between two men. It is a tale of loss and grief. It is about finding peace in ones community. To Star Treks Captain Picard, Gilgamesh was about finding friendship in adversity. For the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, writing about the epic was a way to escape our age, one marked by terrible disasters for the Arab world. To the psychoanalyst Carl Jung, the epic was about incestuous desire; to the German emperor Wilhelm II, it was about power. To the classicist Andrea Deagon, Gilgamesh is a fellow insomniac. In a myriad of different ways, the epic continues to concern us.

In 2019, I had the pleasure of publishing a Danish translation of the epic with my father, the poet Morten Sndergaard. It was on our book tour that I truly realized the power and breadth of the epics appeal. During a Q&A, a young woman whose partner had recently died asked me what the epic had to say about coping with loss. The next week a member of the audience teared up as I talked about the heroes destruction of the Cedar Forest: that was the week of the Amazon wildfires. Its just too real, he said. As a restless young man myself, I cant deny that I also feel a connection with Gilgamesh. When the book tour was over, my father said that Gilgamesh reminded him of a punching bag. It just hangs there. You come up to it, spar with it. You push yourself and grow stronger, wiser. But the epic just hangs there, ready for the next reader. When youre done with it, it says, Is that all youve got?

One reason for the epics appeal is that it lures the reader in with a mix of wild energy and sober reflection. Gilgamesh the hero is youthful and rash, but Gilgamesh the epic is much more melancholic, full of meditations on death and the burden of community. The heros exploits move the plot forward from one scene of excitement to the next, but increasingly tragic

Gilgamesh confounds many of the expectations we bring to the epic genre, in part because those expectations were shaped by the later Classical tradition, and in part because the epic itself is bent on showing how Gilgamesh falls short of the heroic ideals he sets for himself. He weeps and worries, hugs and begs, mourns and dreams far more than he fights. He never quite becomes the hyper-masculine warrior we are told to expect in the opening pages. His greatest military success, defeating the monster Humbaba, is made possible only by the intervention of his mother. In the end, the most significant event in his life is not a heroic triumph but a resounding defeat: his failure to achieve immortality.

The not-quite-epic style gives the story a playful side. It is often ironic and subversive, poking fun at its hero or critiquing his society. But the playfulness is always balanced by the gravity of its themes. The epic tackles the darkest topics without flinching: death, the loss of a loved one, qualms about committing murder, catastrophe on an apocalyptic scale. These are disturbing topics but also topics that resonate forcefully across time and bring the epic alive. For all its bleakness, the theme of death is the most vivid of the story, that which makes it feel so quintessentially human.

There is a danger in projecting onto ancient poems our modern fascination with metanarrative and stories about stories, but Gilgamesh seems to welcome that projection. Its climax is not a battle or a kiss but an epic within the epic: the tale of the Flood recounted by the immortal sage Utanapishti. This autobiographical account is then mimicked by Gilgamesh himself when he writes down the story of his life. As he does so, he finally finds a semblance of solace: He came back from far roads, exhausted but at peace, as he set down all his trials on a slab of stone. The epic shows both the tremendous power of storytelling and the cost at which it is purchased. Through stories, the teller can achieve the next best thing to immortality: eternal life in literature. But to tell ones story is also to stop moving, surrender ones identity to the reader and become fixed as a character once and for all. In