I would like to thank those writers who responded to my questions about their relationship with Gilgamesh, many of whom I quote in the book. In particular I am grateful for the care and detailed help of Iain Bamforth, Edward Hsu, Jenny Lewis, Charles Schmidt and Harry Gilonis, who sent me in useful directions. I would also like to raise my hat to my Princeton line editor Jodi Beder: her contributions are warmly appreciated.

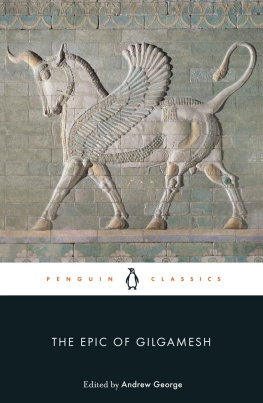

To the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, where I enjoyed a Visiting Fellow Commonership in 20178, thanks are due, and at Trinity in particular to Professor Angela Leighton and for his patience and kindness to Professor Nicolas Postgate; also in Cambridge to Dr Selena Wisnom and at St Johns College to Professor Patrick Boyde. I had the pleasure of hearing and meeting Professor Andrew George during the writing of this book and am entirely in debt to him for his illuminating scholarship and good humour, which I hope will extend to the errors and omissions of this book.

Preface

So poetry tackles what is not yet, what is lost, what the kestrel is when it is all kestrel.

R. F. Langley

GILGAMESH is a confusion of stories. There is, first, the broken story told by the poem itself. Then, the story of why the clay tablets it was written on got broken into so many fragments, scattered over a vast area from Turkey to southern Iran, and were lost for millennia. Then, how it was re-discovered, by accident and then by design, in various archaeological digs, the conventional heroisms of Victorian derring-do spurred on by competing expeditions from Germany and France. And how the discoveries continue to this day, sometimes thanks to excavation, other times as the result of museum and archive sackings and antiquity-trafficking, in the wake of wars and anarchy.

The story of the poems recovery is nothing short of a metonymic account of almost two centuries of Middle Eastern history.

And how exactly were the eleven (or twelve) tablets of the poem reassembled, a jigsawactually, several jigsaws in different languages and from periods separated by centuries. The pieces, drawn from dozens of sites, are now scattered through dozens of the worlds museums and libraries, in Berlin, Paris, London, Oxford, Chicago, Baghdad the fragments mixed in with tens of thousands of unrelated fragmentsinventories, invoices, omen texts, school exercises, letters, laws, laments.

And then, the most heroic story of all, how the complex lost languages in which the poem was writtenOld Babylonian, Standard Babylonian, Hittite and others which ceased to be voiced and written thousands of years agowere gradually recovered, first the cuneiform script, and then the sounds and sense, a continuing triumph of philological genius and perseverance. Gilgamesh even in its damaged present form is an ongoing labour of scholarship and love.

Gilgamesh has become a canonical work. Schoolchildren learn the story. Undergraduates encounter it as an assigned or recommended book. Enkidu, who loves animals, saves them from trappers and hunters, and becomes the best friend a man could have, is a favourite with younger readers, the most popular figure in the story, a talisman for ecologists. The poem leaves so much space for the readers imagination that when we read it, while we all go on the same narrative journey and reach the same destination, we carry different luggage with us. Your vision of the land around Uruk-the-Sheepfold, of Humbabas cedar (or pine) forest, of Uta-napishtis boat, of the view of Uruk from the walls, will differ from mine. The netherworld for you and for me will appear quite different.

If we read Homer or Virgil we share much more common ground, in part because Homer describes more, in part because the poems have been so thoroughly assimilated into our literary and artistic culture that we know the characters and scenes even before we read the poems. Gilgamesh is sparse by comparison. It is 3200 lines and part-lines long (at present: if ever fully restored it will run to about 3600 lines) as against 15,693 lines in the Iliad and 12,110 in the Odyssey, not to mention the 9896 lines of the Aeneid. The textures of the Greek poems, and how much more so of the Latin, are worked and re-worked: there is much deliberate poetry in them and little approximation. The Aeneid in particular is charged with poetic intent, and we are aware throughout of the presence not only of the poet, whose mastery of prosody and poetic form is unrivalled, but also of his chief reader the emperor Augustus, whom the poem obliquely celebrates. We are also aware of echoes of some of the poems upon which Virgil modelled his.

Gilgamesh is quite another kind of poem. It came together over centuries and is on the face of it less artful than Virgil and Homer. It does not appear to have a specific political or civic target. We are not even clear if it had an audience, or who such an audience might have comprised. In modern terms, it has not had time to sink in, in part at least because it has not yet found its great translator, its George Chapman (Ovid), its John Dryden (Virgil), its Alexander Pope (Homer), its Edward Fitzgerald (Omar Khayyam). Not for lack of trying: there are numerous modern renditions, but Gilgamesh is still in waiting. The most convincing contemporary translations are by scholars who insist that their versions acknowledge the gaps and difficulties of the original. Yet it is a poem widely read by contemporary writers, who draw a variety of formal and imaginative energies from it.