Introduction

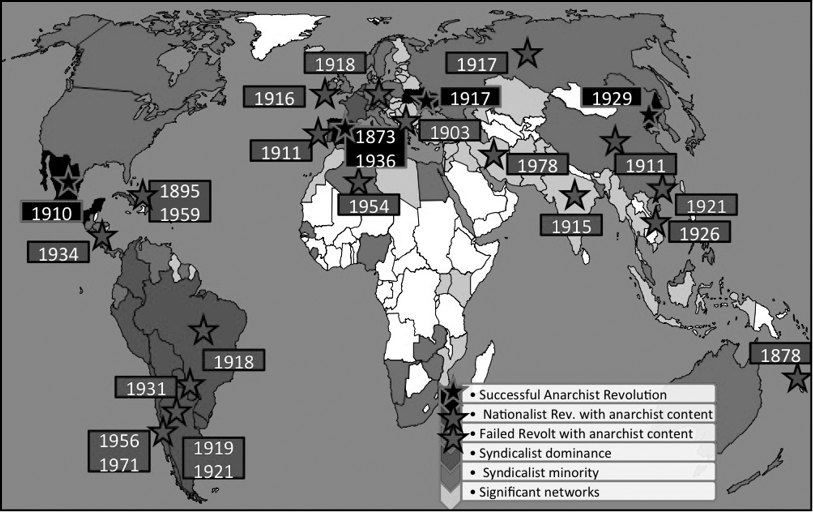

The revolutionary vision of anarchism gained a foothold in the imagination of the popular classes with the rise of the anarchist strategy of revolutionary syndicalism in the trade unions affiliated to the First International. It has since provided the most devastating and comprehensive critique of capitalism, landlordism, the state, and power relations in general, whether based on gender, race, or other forms of oppression. In their place it has offered a practical set of tools with which the oppressed can challenge the tiny, heavily armed elites that exploit them. Anarchism and syndicalism have been the most implacable enemies of the ruling-class industrialists and landed gentry in state and capitalist modernisation projects around the world. They have also unalterably shaped class struggle in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, producing several key effects that we now presume to be fundamental aspects of civilised society.

This broad anarchist tradition had constructed, and continues to construct today, concrete projects to dissolve the centralist, hierarchical, coercive power of capital and the state, replacing it with a devolved, free-associative, horizontally federated counter-power. This concept of counter-power echoes that of radical feminist Nancy Frasers subaltern counterpublics. In essence, her subaltern counterpublics are socio-political spheres separated from the mainstream, which serve as training-grounds for agitational activities directed towards wider publics. Likewise, anarchist counter-power creates a haven for revolutionary practice that serves as a school for insurgency against the elites, a beachhead from which to launch its assault, and as the nucleus of a future, radically egalitarian societywhat Buenaventura Durruti called the new world in our hearts. As Steven Hirsch notes of the Peruvian anarchist movement, they transmitted a counter-hegemonic culture to organised labour. Through newspapers, cultural associations, sports clubs, and resistance societies they inculcated workers in anti-capitalist, anti-clerical, and anti-paternalistic beliefs. They also infused organised labour wit an ethos that stressed self-emancipation and autonomy from non-workers groups and political parties. In a sense, anarchist counter-culture provides the oppressed classes with an alternate, horizontal socio-political reality.

Beyond the factory gates, the broad anarchist tradition was among the first to systematically confront racism and ethnic discrimination. It developed an antiracist ethic that extended from the early multi-ethnic labour struggles of the Industrial Workers of the World, through anti-fascist guerrilla movements of Europe, Asia, and Latin America in the 1920s 1950s, to become a key inspiration for the New Left in the period of African decolonisation, and later of indigenous struggles today in regions like Oaxaca in Mexico. But anarchism was more than a mere hammer to be used against prejudice: over the last one hundred and fifty years, generations of proletarians developed a complex toolkit of ideas and practices that challenged all forms of domination and exploitation. The world has changed dramatically over those decades, shaped in part by the contribution of anarcho-syndicalists and revolutionary syndicalists, a contribution usually relegated to the shadows, derided, or denied, but woven into the social fabric of contemporary society.

The Coherence of the Broad Anarchist Tradition

Anarchism did not rise as a primordial rebel state of mind as far back as Lao Tzu in ancient China or Zeno in ancient Greece as many have speculated, nor was it the child of declining artisanal classes facing extinction by modern modes of production as so many Marxist writers would have us believe. On the contrary, it grew within the seedbed of organised trade unions as a modern, internationalist, revolutionary socialist, and militant current with a vision of socialism-from-below, in opposition to classical Marxisms imposition of socialism-from-above.

Marxism has historically included some minority libertarian currents, such as the Council Communists, Left Communists, and Sovietists of the 1920s. However, the vast majority of historical Marxist movements strived for revolutionary dictatorship based upon nationalisation and central planning. Every Marxist regime has been a dictatorship. Every major Marxist party has renounced Marxism for social democracy, acted as an apologist for a dictatorship, or headed a brutal dictatorship itself. Even those mainstream Marxists who critique the horrors of Stalin or Mao defend Lenin and Trotskys regime, which included all the core features of later Marxist regimeslabour camps, a one-party dictatorship, a secret political police, terror against the peasantry, the repression of strikes, independent unions and other leftists, etc. Marxism must be judged by history and the authoritarian Marxist lineage that exists therein: not Marxism as it might have been, but Marxism as it has been. Accordingly, I do not refer to Stalinism but rather simply to Marxism or to Bolshevism in the post 1917 period.

Over the past 15 decades, the global anarchist movement and its progeny, the syndicalist movement, have been comprised mainly of the industrial working classseamen and stevedores, meat-packers and metalworkers, construction and farm workers, sharecroppers and railwaymenas well as of craftspeople such as shoemakers and printers, and of peasants and indentured labourers, with only a sprinkling of the middle classes, of doctors, scientists, dclass intellectuals, and journalists. It developed a sophisticated theory of how the militant minority related to broader trade unions, and to the popular classes as a whole, seeking to move beyond an insurrectionary general strike (or lock-out of the capitalist class) to a revolutionary transformation of society. The movement sought to achieve this through organised, internally-democratic, worker-controlled structures, including unions, rank-and-file networks, popular militia, street committees, consumers co-operatives, and popular policy-making assemblies.

Many would ask what the relevance of the broad anarchist tradition would be in todays world, a world of nanotechnology and space tourism far removed from the gas-lit origins of the movement. The world has changed. In 1860, Washington D.C. was a rough, provincial town. Today, it is the unchallenged imperial capital of the world, the heart of the US hyperpower. The telegraph had already begun to unite people, just as barbed wire divided their landyet successful trans-Atlantic telephone cables and the Fordist production line had yet to see daylight. Many countries, notably Germany, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Poland, the Baltic and Balkan states, Vietnam, and South Africa, did not yet exist, nor did much of the Middle East. Those countries that did, like Argentina, Egypt, Algeria, and Canada, were narrow riverine or coastal strips of the giant territories they would later lay claim to. In 1860, women, even in countries as advanced as France, would have to wait a lifetime merely to secure the bourgeois vote. Serfdom and slavery were widespread, and the divine right of kings reigned supreme over vast territories, including Imperial Japan, China, and Russia, and the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires.