Introduction

Today the most powerful force for social transformation is the working class movement. Anarchists must recognize the usefulness and the importance of the workers movement, must favour its development, and make it one of the levers for their action, doing all they can so that it, in conjunction with all existing progressive forces, will culminate in a social revolution which leads to the suppression of classes and to complete freedom, equality, peace and solidarity among all human beings.

Errico Malatesta

This book focuses on the relationship between anarchism and syndicalism in the Spanish trade union organisation the Confederacin Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) from its foundation in 1910 to the proclamation of the Spanish Second Republic in 1931. The influence of anarchism had been felt in the Spanish labour movement since the creation of the first national labour movement as part of the Spanish section of the International Workingmens Association (IWMA) in 1870 and was evident from the beginning in the CNT, in which the majority of leading militants described themselves as anarchists. However, the CNT was not an exclusively anarchist organisation, nor could the Spanish anarchist movement be reduced to the CNT. It is the area in which working-class resistance was organised and united within the CNT, and intersected with the labour policy of the anarchist movement, that forms the heart of this study.

Both anarchism and syndicalism are ideologies with an internationalist outlook, and the Spanish movement was heavily influenced by ideas and events from outside its borders, albeit these were adapted to Spanish reality. There was dynamic interrelationship between the different national movements as well as between these and the international libertarian movement as a whole. The importance of events elsewhere can be gauged by the space given to them in the Spanish libertarian press, articles on them by leading anarchist and syndicalist militants, and the importance given to international meetings. The almost constant repression faced by Spanish militants during the period under study, which sent hundreds into exile, meant that the flow of ideas back and forth across the Pyrenees was constant during this period. So any attempt to understand the relationship between anarchism and syndicalism in Spain cannot simply be based on national factors but must also take into account developments in the global libertarian movement. Moreover, it was the repercussions of international events, in particular the First World War and the Russian Revolution especially the latters subsequent development and internationalization, and the wave of repression that spread across much of Europe that would cause such confusion and division within both syndicalism and the anarchist movement and would have a decisive impact on relations be tween the two.

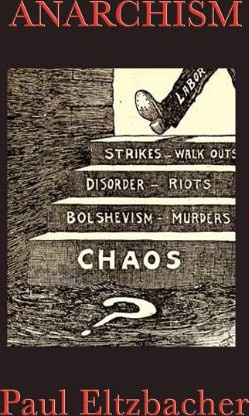

Anarchism developed as an ideology in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century due to the socio-economic changes brought about by the industrial revolution and the triumph of liberal political economy. It emerged as part of the universal socialist movement, which aimed at the overthrow of capitalism, concurrent with and as a reaction to the development of Marxism. Although sharing many Marxist criticisms of the capitalist system as well as the final goal of the Marxists the creation of a classless society without the exploitation of one by another and where the state had withered away anarchists differed from them in various aspects. They saw the poorer workers and agrarian workers as the most revolutionary sectors of the working class (although not simply lumpenproletariat as often claimed), believed in the possibility of achieving revolution immediately through insurrection instead of waiting for capitalism to mature and fulfill the supposed historic role assigned it in the preparation of the road towards socialism and, finally, rejected any role for the state in the transformation of societ y to socialism.

Anarchists opposed the state as they considered it an instrument of the dominant (capitalist) class to control society. The state was not a natural phenomenon. It was human-made to achieve domination. Only with its complete destruction could society develop freely and naturally. The basic goal of anarchism is to achieve the maximum freedom for the individual so that all can develop to their maximum potential. However, anarchists do not conceive of humans living outside society. Human beings are social animals society is their natural home therefore, to be free they must live in a free society. The principal objective of the anarchist movement was to create such a society, organised from the bottom up. Organisations formed freely by individuals would be responsible for production and distribution, be organised horizontally (locally, regionally, and nationally according to the will of the people), and evolve, adapt, or disappear according to the needs of society. Of course, there was continuous debate as to exactly how this society should be (or should not be) organised, about the limits of individual and collective responsibility, et cetera, but fundamental to anarchists was their view of the state. A struggle against repression limited to an attempt to take control of the state was bound to be truncated. There was no guarantee that those victorious in a revolution would not simply become a new ruling class. Control of the state was neither a means nor an end to emancipation: the state had to be destroyed.

Anarchism as an ideology was born during the internal debates of the first-ever international labour organisation, the IWMA, and it was through this that its ideas first penetrated the Iberian peninsula. Anarchist philosophy developed in relation to the advance of capitalist society and human experience and knowledge, evolving into different tendencies, each with its own nuances, at times coalescing, at t imes dividing.

The reasons for the strength and persistence of anarchism in the Spanish working class have long been debated among historians. Initial serious attempts to explain this phenomenon fell victim to Marxist sophistry or the patronising interpretations of liberal historians, which were often more anthropological than historical. Blinded by their own ideology, Marxist historians, with Eric Hobsbawm at the fore, clung to simplistic, reductionist interpretations in which anarchism was presented as a utopian, primitive ideology, the reflection of a pre-industrial, backward labour movement which in the course of capitalist development would logically evolve towards Marxism. The unsatisfactory conclusion was that the success of anarchism was either the result of a fanatical quasi-religious faith among the Andalusian peasantry, which slowly infiltrated industrialised areas through emigration in the early twentieth century, or of a specific Spanish temperament which was somehow uniquely suited to an ideology whose origins lay in the French mutualism of Proudhon and the writings of the Russian aristocrat Mikhail Bakunin. These deliberately simplistic interpretations have been superseded by more rigorous historical studies which, rather than basing their research on the peculiarity of the strength of anarchism in Spain, placed the appeal of anarchism among the working class within the economic and sociopolitical reality of a centralised yet culturally divided, economically backward yet modernising, military-dominated state. As Josep Termes, one of the foremost historians of the Catalan and Spanish labour movement, clarifies, in Spain anarchism was a response by the industrial workers to social inequality, [perhaps] utopian or idealistic, but no less rational and logical than that given to Europe by Marxis t socialism.