The Project Gutenberg EBook of Anarchism, by Paul Eltzbacher

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Anarchism

Author: Paul Eltzbacher

Translator: Steven T. Byington

Release Date: July 10, 2011 [EBook #36690]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ANARCHISM ***

Produced by Fritz Ohrenschall, Martin Pettit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note:

The corresponding scanned page can be seen by clicking on the page number at the right.

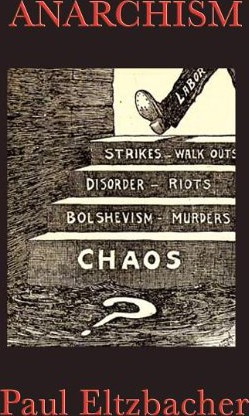

Anarchism

ELTZBACHER

ANARCHISM

BY Dr. PAUL ELTZBACHER

Gerichtsassessor and Privatdozent in Halle an der Saale

Translated by

STEVEN T. BYINGTON

Je ne propose rien, je ne suppose rien, j'expose

NEW YORK: BENJ. R. TUCKER.

London: A. C. Fifield.

1908.

Copyright, 1907, by

Benjamin R. Tucker

Gratefully dedicated to the memory of my father

Dr. Salomon Eltzbacher

1832-1889

CONTENTS

| Page |

| TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE |

| BOOKS REFERRED TO |

| INTRODUCTION |

| Chapter I. THE PROBLEM |

| 1. General |

| 2. The Starting-point |

| 3. The Goal |

| 4. The Way to the Goal |

| Chapter II. LAW, THE STATE, PROPERTY |

| 1. General |

| 2. Law |

| 3. The State |

| 4. Property |

| Chapter III. GODWIN'S TEACHING |

| 1. General |

| 2. Basis |

| 3. Law |

| 4. The State |

| 5. Property |

| 6. Realization |

| Chapter IV. PROUDHON'S TEACHING |

| 1. General |

| 2. Basis |

| 3. Law |

| 4. The State |

| 5. Property |

| 6. Realization |

| Chapter V. STIRNER'S TEACHING |

| 1. General |

| 2. Basis |

| 3. Law |

| 4. The State |

| 5. Property |

| 6. Realization |

| Chapter VI. BAKUNIN'S TEACHING |

| 1. General |

| 2. Basis |

| 3. Law |

| 4. The State |

| 5. Property |

| 6. Realization |

| Chapter VII. KROPOTKIN'S TEACHING |

| 1. General |

| 2. Basis |

| 3. Law |

| 4. The State |

| 5. Property |

| 6. Realization |

| Chapter VIII. TUCKER'S TEACHING |

| 1. General |

| 2. Basis |

| 3. Law |

| 4. The State |

| 5. Property |

| 6. Realization |

| Chapter IX. TOLSTOI'S TEACHING |

| 1. General |

| 2. Basis |

| 3. Law |

| 4. The State |

| 5. Property |

| 6. Realization |

| Chapter X. THE ANARCHISTIC TEACHINGS |

| 1. General |

| 2. Basis |

| 3. Law |

| 4. The State |

| 5. Property |

| 6. Realization |

| Chapter XI. ANARCHISM AND ITS SPECIES |

| 1. Errors about Anarchism and its Species |

| 2. The Concepts of Anarchism and its Species |

| CONCLUSION |

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE

Every person who examines this book at all will speedily divide its contents into Eltzbacher's own discussion and his seven chapters of classified quotations from Anarchist leaders; and, if he buys the book, he will buy it for the sake of the quotations. I do not mean that the book might not have a sale if it consisted exclusively of Eltzbacher's own words, but simply that among ten thousand people who may value Eltzbacher's discussion there will not be found ten who will not value still more highly the conveniently-arranged reprint of what the Anarchists themselves have said on the cardinal points of Anarchistic thought. Nor do I feel that I am saying anything uncomplimentary to Eltzbacher when I say that the part of his work to which he has devoted most of his space is the part that the public will value most.

And yet there is much to be valued in the chapters that are of Eltzbacher's own writing,even if one is reminded of Sir Arthur Helps's satirical description of English lawyers as a class of men, found in a certain island, who make it their business to write highly important documents in closely-crowded lines on such excessively wide pages that the eye is bound to skip a line now and then, but who make up for this by invariably repeating in another part of the document whatever they have said, so that whatever the reader may miss in one place he will certainly catch in another. The fact is that Eltzbacher's work is an admirable model of what should be the mental processes of an investigator trying to determine the definition of a term which he finds to be confusedly conceived. Not only is his method for determining the definition of Anarchism flawless, but his subsidiary investigation of the definitions of law, the State, and property is conducted as such things ought to be, and (a good test of clearness of thought) his illustrations are always so exactly pertinent that they go far to redeem his style from dullness, if one is reading for the sense and therefore cares for pertinence. The only weak point in this part of the book is that he thinks it necessary to repeat in print his previous statements wherever it is necessary to the investigation that the previous statement be mentally renewed. But, however tiresome this may be, one gets a steady progress of thought, and the introductory part of the book is not very long at worst.

The collection of quotations, which form three-fourths of the book both in bulk and in importance, is as much the best part as it is the biggest. Here the prime necessity is impartiality, and Eltzbacher has attained this as perfectly as can be expected of any man. Positively, one comes to the end of all this without feeling sure whether Eltzbacher is himself an Anarchist or not; it is not until we come to the last dozen pages of the book that he lets his opposition to Anarchism become evident. To be sure, one feels that he is more journalistic than scientific in selecting for special mention the more sensational points of the schemes proposed (the journalistic temper certainly shows itself in his habit of picking out for his German public the references to Germany in Anarchist writers). Yet it is hard to deny that there is legitimate scientific importance in ascertaining how much of the sensational is involved in Anarchism; and, on the other hand, Eltzbacher recognizes his duty to present the strongest points of the Anarchist side, and does this so faithfully that one often wonders if the man can repeat these words without feeling their cogency. So far as any bias is really felt in this part of the book it is the bias of over-methodicalness; now and then a quotation is made to go into the classification at a place where it will not go in without forcing, and perspective is distorted when some obiter dictum that had never seemed to its author to be worth repeating a second time is made to serve as illuminant now for this division of the "teaching," now for that, till it seems to the reader like a favorite topic of the Anarchist. However, the bias of methodicalness is as nearly non-partisan as any bias can be, and its effect is to put the matter into a most convenient form for consultation and comparison.