First published 1975 by Transaction Publihsers

Publihsed 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon 0X14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1975 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2010005519

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hoffman, Robert Louis, 1937

Anarchism as political philosophy / [edited by] Robert Hoffman.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Atherton Press, 1970.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-202-36364-6 (alk. paper)

1. Anarchism 2. Anarchism--Philosophy. 3. Anarchism--Political aspects. I. Title.

HX833.H63 2010

321.07--dc22

2010005519

ISBN 13: 978-0-202-36364-6 (pbk)

Consulting Editors

ELY CHINOY

Smith College

SOCIOLOGY

GILBERT GElS

California State College, Los Angeles

SOCIAL PROBLEMS

MAXINE GREENE

Teachers College, Columbia University

EDUCATION

ROBERTS. HIRSCHFIELD

Hunter College

POLITICAL SCIENCE

ARNOLD S. KAUFMAN

University of Michigan

PHILOSOPHY

JEROME L. SINGER

City College, CUNY

PSYCHOLOGY

DAVID SPITZ

Ohio State University

POLITICAL THEORY

NICHOLAS WAHL

Princeton University

COMPARATIVE POLITICS

FREDERICK E . WARBURTON

Barnard College

BIOLOGY

Robert Hoffman

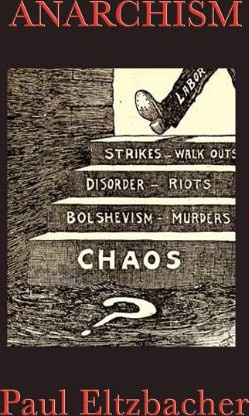

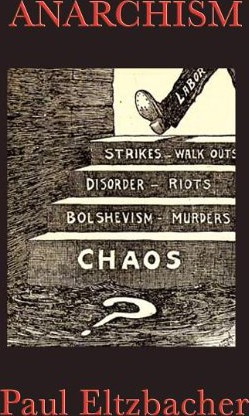

Anarchy means the complete absence of government and law.

Government is instituted to create and preserve order in society and to protect people from violence done them by their neighbors or foreigners.

Therefore, anarchy must mean the complete absence of order and protectionchaos.

Anarchism is a theory which advocates anarchy.

Therefore, anarchism advocates disorder and violence chaos.

This seems logical. The premises appear to make the conclusions inescapable.

But anarchists claim that just the opposite is true. They say that a society ruled by government cannot be orderly, that government creates and perpetuates both disorder and violence.

Government is anarchy! wrote Proudhon, an anarchist who loved paradox.

Apparently there is an abyss in meaning between anarchists and conventional thinking about what they advocate. The political climate has rarely been conducive to a crossing of this gap, so that anarchism has been talked about far more than it has been understood.

Anarchists have been viewed at best as rather foolish idealists; more often they have been regarded as dangerous, even frightening threats to the maintenance of justice and social tranquility. There is a real basis for these fears, but historically the popular image of anarchists has most often been gross caricature.

People usually have associated them with revolutionary violence, which at one time was advocated by many anarchists. Terrorism and assassination were often thought to be virtually synonymous with anarchism, although actually anarchists rarely committed such acts. Attributed to themsometimes falsely were a number of notorious incidents of bomb-throwing and the killing of public officials, crimes that did much to form this popular image.

To this association of anarchism with violent incidents were added other, largely fantastic, notions created mainly out of anxiety, fear, and ignorance; anarchists were regarded as the most terrifying and hateful of people. These attitudes were often exploited and intensified by politicians, police officials, and newspapers seeking scapegoats for a variety of social ills and popular unrest.

For years it was common to condemn political opponents of many different sorts as anarchiststhe ultimate term of opprobriumand to blame most violence and civil disorder upon anarchists. After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 anarchist movements declined in most places and revolutionary Communists took the place of anarchists as the bogeymen to be discovered in every corner. More recently new currents of rebellion have arisen to which it is difficult to attach the Communist label, and the dread specter of anarchism has been called to service again.

As the last selection in this volume argues, there is reason to perceive anarchism in the contempory situation. This is not to say that the exorcisers of political devils are right in their accusations and fear-mongering: both anarchists and Communists have rarely been what, or even who, their enemies said they were. Dangers they may have been, but this is one area where the admonition Know thine enemy most often results only in the collection of distortions and falsehoods.

In most respects, anarchists have been ordinary men, not devils. If anything has distinguished them from others it has not been evil character, but an extraordinary passion for what they regard as justice.

They have, however, without exception been rebels. A spirit of rebellion against the established order of society is the single most distinctive quality of anarchist convictions, and one of the few that all share. The rebellion may be purely philosophical, it may seek change in the existing order by pacific means, or it may be acted out through violent agitation and revolution. The rebellious spirit is directed against all social conditions thought to be repressive: this usually means private property as well as government, and it means also a host of other institutions that many nonanarchists regard as essential constituents of a just and orderly society.

The anarchist assault on what others believe to be vital to their very existence makes anarchism intolerable. This is the substance behind past fears about anarchism. Repudiation of what seems sacred naturally excites the strongest and most unrelenting opposition, although the expression of opposition most often has been related only remotely to the reality of the anarchist threat.

Rejection of anarchism also takes a more rational form, though a hardly less total one. Suppose, it may be said, that no particular institution or custom is sacrosanct; nevertheless, we must have an organized society, which requires government, and other institutions as well. Anarchism is fundamentally antisocial because of its insistence on individual liberty. Any philosophy which rejects society is irresponsible, impossible, and unworthy of serious consideration.

Yet anarchism is anything but antisocial; indeed, for most anarchists a concern for a just and integral society is more primary than their concern for individual liberty. The distinctiveness of their position results from their conviction that men can be really social, and society truly real, only when individuals are really freeand this means ordering society not through the dictates of power but through voluntary cooperation and self-imposed restraints.