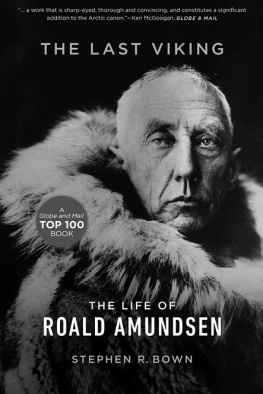

Also by Stephen Bown

Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail

Forgotten Highways: Wilderness Journeys Down the Historic Trails of the Canadian Rockies

Merchant Kings: When Companies Ruled the World, 1600 1900

1494: How a Family Feud in Medieval Spain Divided the World in Half

First published in 2012

by Aurum Press Ltd, 7 Greenland Street, London NW1 0ND

First published in the United States by Da Capo Press in 2012

This eBook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

Stephen Bown, 2012

The right of Stephen Bown to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

eBook conversion by CPI Group

ISBN 978-1-78131-084-7

And yet even today we hear people ask in surprise: What is the use of these voyages of exploration? What good do they do us? Little brains, I always answer to myself, have only room for thoughts of bread and butter.

Roald Amundsen, The South Pole

In spite of the long time I had spent in the Arctic I was always longing to go back again. Kipling says that the man who hears the East a-calling never hears anything else, but the Arctic and the ice call just as strongly to some people.

Helmer Hanssen, Voyages of a Modern Viking

No man more than the explorer is tempted to adopt the doctrine of ends justifying the means. An explorer soon discovers that the world is full of busybodies righteously ready to save him, as they probably think, from himself. The only way to deal with such people is to agree to their terms and then go ahead as one pleases. There are enough legitimate discouragements in the world without submitting to artificial ones.

Lincoln Ellsworth, Beyond Horizons

I tried to work up a little poetrythe ever-restless spirit of man, the mysterious, awe-inspiring wilderness of icebut it was no good; I suppose it was too early in the morning.

T HE STANDARD OF Fascist Italy is floating in the breeze over the ice of the Pole, radioed General Umberto Nobile, commander of the dirigible Italia, on May 24, 1928. The enormous airship and its crew of sixteen had flown from their base on Spitsbergen the day before and were now leisurely circling the frozen expanse at the top of the world. In the tiny main cabin strapped underneath the monstrous gas chamber, a gramophone scratched out the Italian folk song The Bells of San Giusto, and the men celebrated with a homemade liqueur.

A month earlier, Pope Pius XI had publicly blessed the crew and commander in Italy, urging them to consecrate the summit of the world, and had presented them with an enormous ceremonial oak cross for that purpose. It was impossible for the crew to disembark from the cabin onto the ice due to winds that kept the airship 150 metres in the air, and the men struggled to manoeuvre the great cross out the cabin door. They solemnly watched it plummet to the ice with the flag of Italys National Fascist Party attached to it, fluttering in the polar wind. Then, in a religious silence, they tossed out a Milanese coat of arms and a little medal of the Virgin of the Fire.

After the brief ceremony, which also included playing the Fascist battle hymn Giovinezza followed by a flourish of salutes, the airship slowly turned around and began to struggle against headwinds and fog on its way back south to Spitsbergen. The visibility being poor, Nobile couldnt determine the Italias location. The crew became disoriented, and Nobile ordered the airship to descend closer to the pack ice for a better view. They were still almost three hundred kilometres northeast of Spitsbergen when the rear of the airship became heavy and lurched toward the ice. Alarmed, Nobile and his officers tried to regain control over the Italia by increasing the speed of the propellers. But it was too late. The rear end of the dirigible hit and scraped along the jagged surface of the ice. There was a fearful impact, Nobile wrote later. Something hit me on the head, then I was caught and crushed. Clearly, without any pain, I felt some of my limbs snap. Some object falling from a height knocked me down head foremost. Instinctively I shut my eyes, and with perfect lucidity and coolness formulated the thought: Its all over!

During the impact one man plunged from the cabin onto the ice and died instantly. Nine men scrambled from the wreckage and leaped or were thrown to the ice. As flames erupted from the crippled airship, it spun away in a trail of smoke. Six men were trapped in the cabin, never to be seen again. The nine survivors, several of them severely injured, huddled on the ice amid the detritus of boxes and equipment that had been thrown from the airship while Nobiles little dog Titina, uninjured in the collision, explored the bleak surroundings. After several days without radio contact, Nobile finally accepted that the expedition was indeed in trouble and in need of rescue; only a month of provisions had survived the crash.

Roald Amundsen was attending a public luncheon when news of the disaster reached Oslo. Upon hearing the news he stood up and announced, Im ready to leave at once to do anything I can to help. But as the Norwegian government began planning a rescue expedition, astonishing word came from Italy. Benito Mussolini had refused all assistance from Norway (despite the fact that the airship had probably gone down off Norways northern border), particularly if the rescue were to be led by Amundsen. Nobile and Amundsen had been caught up in a nasty public feud for the past eighteen monthsthe fallout from a previous joint dirigible expedition to the North Poleand Mussolini did not want the honour of Italy besmirched by Nobiles being rescued by his enemy. It would be an affront to Italian dignity. To the budding strongman, then beginning his scheme to reinvigorate Italys image in the eyes of the world and to reposition his country as a powerful player on the international stage, the prospect of the nations of the world coming to Italys rescue was humiliating. Captain Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen, an organizer of the Norwegian rescue operation and a past colleague of Amundsens, wrote in astonishment: I could not rid myself of the idea that it was preferable for the expedition to suffer a glorious