A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Hale and Buckingham families decided early not to participate in a book about their story. While their case was in the public eye, they had been remarkably forthcoming, both in court and in answer to my questions for the Anchorage Daily News, as if to make up for years of public deception. But when it was over, they were eager to leave the stain behind, and a truthful account of their lives, as one of them expressed it, was not a book that could dwell in a good Christian home. Their reluctance was probably a good thing, I decided: No writer could look forward to negotiating a median truth from the traumatized memories of sixteen family members, most of whom had never read a nonfiction book of any kind.

So I set out on my own, with notes and neighbors and public records. Over time, however, individual family members considered how their story could help others and began sharing more and more about their hidden past, profoundly enriching this unusual project. I am grateful especially to Elishaba and Matthew Doerksen, Kurina Rose Hale, Joseph and Lolly Hale, Joshua and Sharia Hale, Betty Freeman, and Jim and Martha Buckingham for the many details they ultimately provided about key moments in their lives. Thanks also to Rose for permission to quote from her husbands letters.

Among the people in and around McCarthy, I am grateful for guidance through the years from Sally Gibert, Ben Shaine, and Rick Kenyon, and appreciate the help for this book from many friends and neighbors, particularly Mark Vail, Jim Edwards, Gary Green, Kelly and Natalie Bay, Kenny Smith, Marci Thurston, Gaia Marrs, Bonnie Kenyon, Dick Mylius, Tom and Catie Bursch, John Adams, Stephens and Tamara Harper, Mike Loso, and Neil Darish. For the Texas story, I owe thanks to Karen Hale, Lucy Hale, and especially Patsy Hale, who I hope will publish her own account of the Hale family. For the New Mexico chapters, I want to thank the neighbors quoted therein, and especially Carolyn Vail for her hospitality, Editha Bartley for permission to quote from family letters, and my friend Joel Gay, for letting me drive his old pickup truck to the mountains.

Many people with the National Park Service were helpful, especially John Quinley, Logan Hovis, Katie Ringsmuth, Danny Rosenkrans, Gary Candelaria, and Hunter Sharp. For perspectives on park policies, I am grateful to Ray and Lee Ann Kreig, Chuck Cushman, Chris Allan, Jim Stratton, Destry Jarvis, Richard Sellars, Jim Rearden, Chuck Hawley, Tony Oney, Anne Beaulaurier, and Wally Cole. For help with civil and criminal legal issues, I thank Richard Payne, Rachel Gernat, Lee de Grazia, Carl Bauman, and Jeff Feldman.

At the Anchorage Daily News, I want to thank my horseback traveling companion, Marc Lester, for his good nature and expert photographic eye, fellow reporters Julia OMalley, Megan Holland, and Joe Ditzler for their help keeping up with courtroom developments, and my editors, David Hulen and Pat Dougherty. Thanks also to fellow writers Mark Kirby and Jack Douglas, for sharing elements of their own research into Robert Hales past, and to Wesley Loy for sharing his CD.

Many of the themes that make Alaska such an appealing subject were first scribed on the landscape by my teacher at Hampshire College, David Smith, who introduced the writings of Leo Marx, Henry Nash Smith, and Roderick Nashto say nothing of Go Down, Moses and the fresh, green breast of the new world that flowered once for Dutch sailors eyes.

This book would not have been written without the early enthusiasm and close attention of my agent, Alice Martell. At Crown Publishers/Random House, I am indebted to Miriam Chotiner-Gardner, Kevin Doughten, and to Charlie Conrad, who worked diligently to keep me from straying too far into copper country ghost stories or the arcana of ANILCA.

I am profoundly grateful to Chip Brown and Blaine Harden for helping me find and hold on to my story. Thanks also to Dan Coyle, Maurice Coyle, Tom Bodett, Nancy Lord, and Rich Chiappone for reading drafts and offering good advice, and to Howard Weaver, Barbara Hodgin, Anne Raup, Todd Stoeberl, and Fred Hirschman for help with photos. The Mesa Refuge and Ted and Frances Geballe gave me places to write portions of this manuscript. For general encouragement and sustenance through this period I want especially to thank Nancy Gordon and Steve Williams, Lisa and Tim Whip, Deb McKinney and Paul Morley, my mom, Peggy, and also my dad, Joe Kizzia, who died while this book about fathers was being born.

A BOUT THE A UTHOR

T OM K IZZIA has traveled widely in rural Alaska writing prizewinning stories about places, people, and politics for the Anchorage Daily News. His work has appeared in the Washington Post and has been featured on CNN. His first book, The Wake of the Unseen Object, was named one of the best all-time nonfiction books about Alaska by the Alaska Historical Society. He lives in Homer, Alaska.

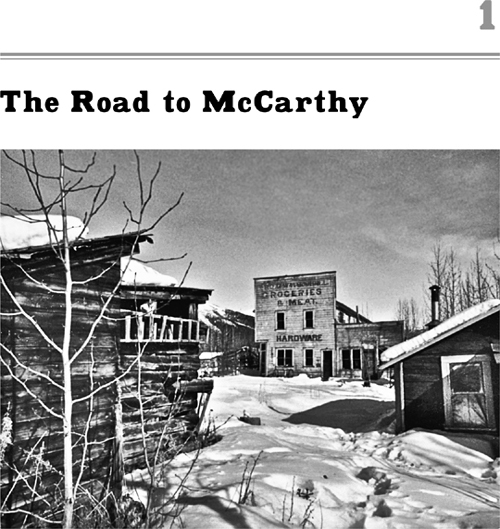

McCarthy, 1983, shortly after creation of WrangellSt. Elias National Park and Preserve ()

A PAIR OF old trucks crept down the street, pushing deep tracks through the snow. Neil Darish stopped shoveling the roof of the McCarthy Lodge to watch. In the back of one pickup, three or four hardy young people stood in the morning cold, looking around at the buildings left over from mining days. Strangers in McCarthy were rare in the middle of January, especially after a storm. It was eight hours from Anchorage through the mountains just to reach the end of the pavement, the last miles of asphalt crumbling and swaybacked by frost. At Chitina, you crossed the Copper River, and it was another sixty miles into the heart of the Wrangell Mountains. The road from Chitina was gravel and followed the bed of a vanished railroad, a route frequently closed in winter by drifts or blocked by freeze-thaw flows of ice that locals attacked with chain saws and winches. At the end of the road was a turnaround and a footbridge. These tourists had apparently made the drive through the blizzard and been enterprising and presumptuous enough to push their trucks across the river ice and into town, rutting up the local snowmachine trails.

Unseen on the low roof, Darish stared as the trucks stopped and emptied their passengers: eight young people in their teens and early twenties, the boys with long hair spilling out from under vintage hats of wool and leather, a few wispy beards, the girls in tattered coats and long flowered skirts down to their snow boots. Darish felt vague misgivings as the strangers peered in the windows of the closed-up hotel across the street. He caught himself: Hed been in McCarthy only a short time, and already hed picked up the local mistrust of visitors hunting souvenirs from the past.

The driver of the first pickup emerged. He was an older man, wiry and bespectacled, with pinched cheeks and a long, unruly beard. He gazed appraisingly at the weathered lodge and the few false-front buildings nearby.

Papa, this is what we thought Fairbanks would look like, said one of the boys.

At this, Darish smiled. He knew Fairbanks was no longer anyones romantic vision of the Last Frontier. Nor was Anchorage with its oil company high-rises, nor Wasilla with its busy highway and chain-store sprawl. McCarthy was another matter. And these new arrivals, he had to admit, looked like they belonged herelike they had just emerged, blinking, from the abandoned copper mines up the mountain.

The bearded father stopped taking the towns measure when he spotted Darish on the roof. At a wave, two youngsters grabbed shovels and scrambled up a ladder to pitch in. Darish tried to shoo them away. He could just picture one of these longhaired boys tumbling to the street. He had too much at stake here to invite a liability lawsuit. Buying the lodge, opening it in winterDarish was trying to restore some can-do pioneer spirit to a melancholy town that had been shutting itself down for decades.