This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf

Copyright 2011 by Sarah Burns

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: Curtis Brown, Ltd.: City Greenery by Ogden Nash, originally published in Holiday Magazine, copyright 1961 by Ogden Nash. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd. El Diario/La Prensa: Excerpt from New Directions for Our Youth from El Diario/La Prensa, April 27, 1989. Reprinted by permission of El Diario/La Prensa. NYP Holdings, Inc.: Excerpt from A Savage Disease Called New York by Pete Hamill, from the New York Post, April 23, 1989. Reprinted by permission of NYP Holdings, Inc., publisher of the New York Post. PARS International Corp.: Excerpt from The Jogger and the Wolf Pack from The New York Times, April 26, 1989, Editorial Section, Section A, page 26, column 1. Reprinted by permission of PARS International Corp. on behalf of The New York Times.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burns, Sarah, [date]

The Central Park Five / Sarah Burns.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59659-8

1. Rape victimsNew York (State)New York. 2. Violent crimes

New York (State)New York. 3. Judicial errorNew York (State)

New York. 4. Criminal justice, Administration ofNew York (State)

New York. I. Title.

HV6568.N5B87 2011 364.153209227471dc22 20100396661

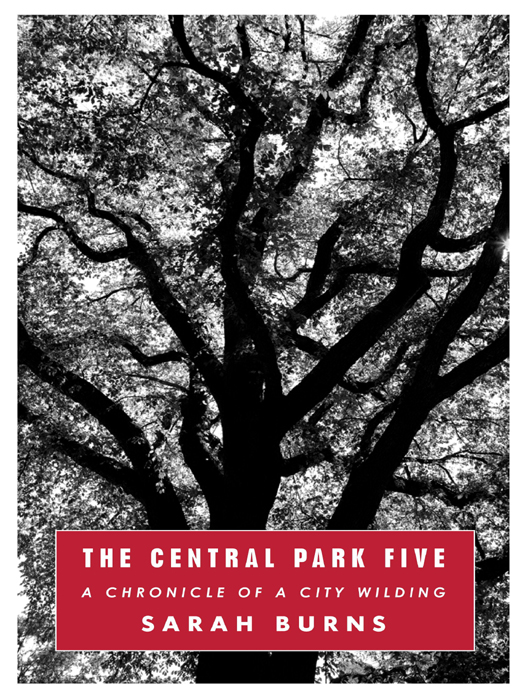

Jacket photograph by Nathan Harger, courtesy of New York

Jacket design by Chip Kidd

v3.1

For Antron, Kevin, Korey, Raymond, and Yusef

I think that everybody heremaybe across the nationwill look at this case to see how the criminal justice system works. This is, I think, putting the criminal justice system on trial.

MAYOR ED KOCH , April 21, 1989

Contents

PREFACE

On December 19, 2002, Justice Charles J. Tejada of the Supreme Court of the State of New York granted a motion to vacate the thirteen-year-old convictions in the infamous Central Park Jogger case. He did so based on new evidence: a shocking confession from a serial rapist and a positive DNA match to back it up. In 1990, Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Korey Wise, Yusef Salaam, and Raymond Santana, Jr., had been convicted and sent to prison for a combination of rape, sexual assault, and attempted murder of a female jogger named Trisha Meili in Central Park on April 19, 1989. The young men had already completed their sentences, having served between almost seven and thirteen yearsbut now they finally had the weight of felony convictions and sexual offender status lifted from their shoulders.

That the victim had been a twenty-eight-year-old successful white investment banker and that the five young men who were convicted were black and Latino teenagers from Harlem was not lost on the public or the media in 1989. In the weeks and months after the brutal rape, a media frenzy erupted, steeped in the emotions and fears that circulated throughout a city paralyzed by crime and a country struggling with its own complicated racial history. The media coverage of the crime exposed a racism, rarely acknowledged or examined, rife in American society, and the language used to describe the supposed perpetrators was filled with imagery of savage, wild animals, the same racist language that had been used to justify lynchings earlier in the century. The vicious rape exposed the deepest fears of New Yorkers in the 1980s, and also in the country at largefears lurking just beneath the surface for over a century: reckless, violent, dark-skinned youths rampaging unchecked, raping and beating a helpless white woman. The outraged response to the crime helped usher in the return of the death penalty in New York State and an era of aggressive law enforcement in New York City.

But even with the convictions vacated, based on a compelling confession and clear forensic evidence and supported by the same district attorney on whose watch the case had been vigorously prosecuted in 1989, many of those who participated in the original prosecutions, including many within the NYPD and one of the ADAs who oversaw the prosecution, still insist on the teenagers guilt. They agree that another man raped the Central Park Jogger, but they argue that his culpability does nothing to contradict the guilty verdicts of the five young men, despite the overwhelming forensic evidence and the teenagers confused and contradictory confessions.

These arguments, coming from individuals and organizations with powerful voices and a wide audience, have been effective in preventing the true story of the Central Park Five from reaching those who had followed the coverage of the convictions back in 1989. Many people have heard of this case, but most do not know the facts, and that the convictions were vacated. If they do, they believe that a legal loophole was responsible for the exoneration, or that because the teenagers gave confessions, they must be guilty.

During the summer of 2003, before my last year of college, I worked as a researcher for civil rights lawyers involved in a civil suit on behalf of Antron, Kevin, Korey, Yusef, and Raymond. The convictions had only recently been vacated, and I was drawn into the stories of the young men who had been wrongly convicted, who had their lives stolen from them. I wanted to know how something like this could have happened. I went on to write my undergraduate thesis about the racism I saw in the media coverage of the case, but the story continued to haunt me, to demand my attention. I wrestled with the many explanations for this miscarriage of justice, and none was simple or satisfying.

The media coverage was certainly not the only reason these teenagers were wrongly convicted. The police, the prosecutors, and the defense lawyers all played a role. But this was not a case of rogue detectives beating confessions out of suspects, or of the police and prosecutors conspiring to frame individuals they knew to be innocent. If that were so, we could blame it all on those bad seeds and move on. Instead, this case exposes the deeply ingrained racism that still exists in our society. It shows us who and what we fear, and how easy it is for us to believe the sensational stories we hear from the media, who often fail to apply the skepticism their profession demands when competition drives them to sell newspapers or attract more viewers.

The false narrative, disseminated by the police and the media, was swallowed whole by the public because it conformed to the assumptions and fears of the city and the country. Everyone bought the story. But the fact that so many continue to promote this narrative tells us that even though we live, as some like to say, in a postracial society, the racism that fueled the original rush to judgment persists, and that we have not evolved enough from the days when even the suggestion that a black man had raped a white woman could lead to a lynching.

My goal in reexamining this case is not just to tell the story and explain the facts, to prove wrong those who refuse to admit that a miscarriage of justice occurred, but also to try to understand the broader forces that shaped the outcome of this case, to figure out a simple, but for me a persistent and nagging, question: How did this happen?