Prologue

Parasailing, pot-holing, the luge: even those sporting activities that appear to require no skill invariably demand an abundance of human qualities that I might only hope to acquire if the Wizard of Oz was in a particularly generous mood. But we can all ride a bike. We have all known what it is to grind agonisingly up a steep hill and freewheel madly down the other side. In its unique dual capacity as mode of transport and childhood accessory, the bicycle has played a formative role in all our lives.

But thinking back, I find that my cycling memories are imbued less with a nostalgic sepia glow than a stark fluorescent glare of fear and failure. Reading the back cover of Rough Ride, the autobiography of former Irish professional cyclist Paul Kimmage, I feel profoundly chastened. Describing a portentous first ride at the age of 6, Kimmage fondly recalls his father immediately removing the stabilisers before plonking his son on the saddle and pushing him off across the car park in front of their Dublin flat. I wobbled, but basically had no trouble and was delighted with myself. Replace trouble with balance, and delighted with myself with repeatedly injured, and you have the encapsulation of my own debut.

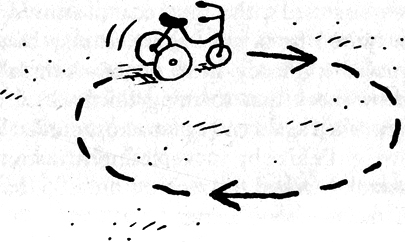

I lived in the tricycle age for far too long, squeaking about Walpole Park on a maroon three-wheeler, its capacious tin boot flamboyantly emblazoned with a royal coat of arms my father had mysteriously acquired from somewhere. It may be that in this fashion I appeared a ghastly little ponce. After all, I hadnt learned to ride without that shaming third wheel until I was almost 8, being pushed again and again across our back garden on a hand-me-down girls bike by an increasingly frustrated mother. I was not a natural. I lacked the reckless bravado that propelled other boys to pedal across Ealing Common with their arms ostentatiously aloft, or, worse, nonchalantly folded.

My first real bike was an ancient machine whose name had a stolid, Empire twang, something like Wayfarer or Valiant, and whose cast-iron forthrightness of design you could never quite shake off by removing the mudguards and fitting a pair of cow-horn handlebars. I should by rights have aspired to a Raleigh Chopper, but then Tomas Kozlowski got one, and seeing those already burgeoning Slavic buttocks unappealingly cleaved by that slender bench saddle I understood with a youthful prescience of which I am still quietly proud that Raleigh Choppers were laughably awful. So it was with Valiant between my pistoning young knees that I breathlessly eluded park-keepers seeking to enforce the new Sling Your Hook, Eddy Merckx no-cycling rule; his were the wheels that shot across mad Mrs Lewiss feet and prompted her to send my parents an admonitory letter that famously included the word delinquent. My Valiant was there outside Gunnersbury Park when a trainee psychopath treated me to my first encounter with a number of other new but much shorter words; there too when, perhaps four seconds later, I accepted that fondly remembered inaugural smack in the mouth.

A succession of inherited shopping models followed, and I had to wait until my sixteenth birthday for my first new bicycle, a ten-speed racer of East German origin. On the way to pick it up, my poor father felt obliged to usher his youngest son into manhood with a dilatory lecture on birth prevention, one whose more poignant euphemisms would recur to me whenever I rode it thereafter. Mercifully almost every component shattered, buckled or split within weeks I had never previously thought of corrosion as a process you could actually sit down and watch happen. On the other hand, its demise did mean that the balance of those important mid-teenage years was spent wobbling about on my fathers foldable Bickerton.

My girlfriend at that time, in fact my wife at this time, had a recurring dream in which I would pedal away from her house naked on the Bickerton. If I tell you that the Bickerton resembled two dwarf unicycles clumsily welded together you will understand that this was not an erotic dream. The Bickerton was a ludicrous machine with the handling characteristics of a human pyramid. Its unique selling point was portability, an asset summarised by a long-running television commercial in which a haughty executive defied a platform full of generously trousered commuters to snigger as he laboriously hauled a huge sack of metallic angles through the ticket barrier, chased and chivvied by taunting voiceover whispers of Bickerton! Bickerton!

Nevertheless, as it became difficult to affect the piping tenor necessary to procure a child ticket from ever more sceptical bus conductors, so the Bickertons social utility increased. I began riding it to pubs and parties, generally returning well-lit and yet, in a hilarious twist of irony, without lights. I crashed into road works and garden fences, and finally broke the Bickertons back in the grand manner, careering into a parked car with such force that I snapped his number plate in half and ended up on the roof.