Contents

ABOUT THE BOOK

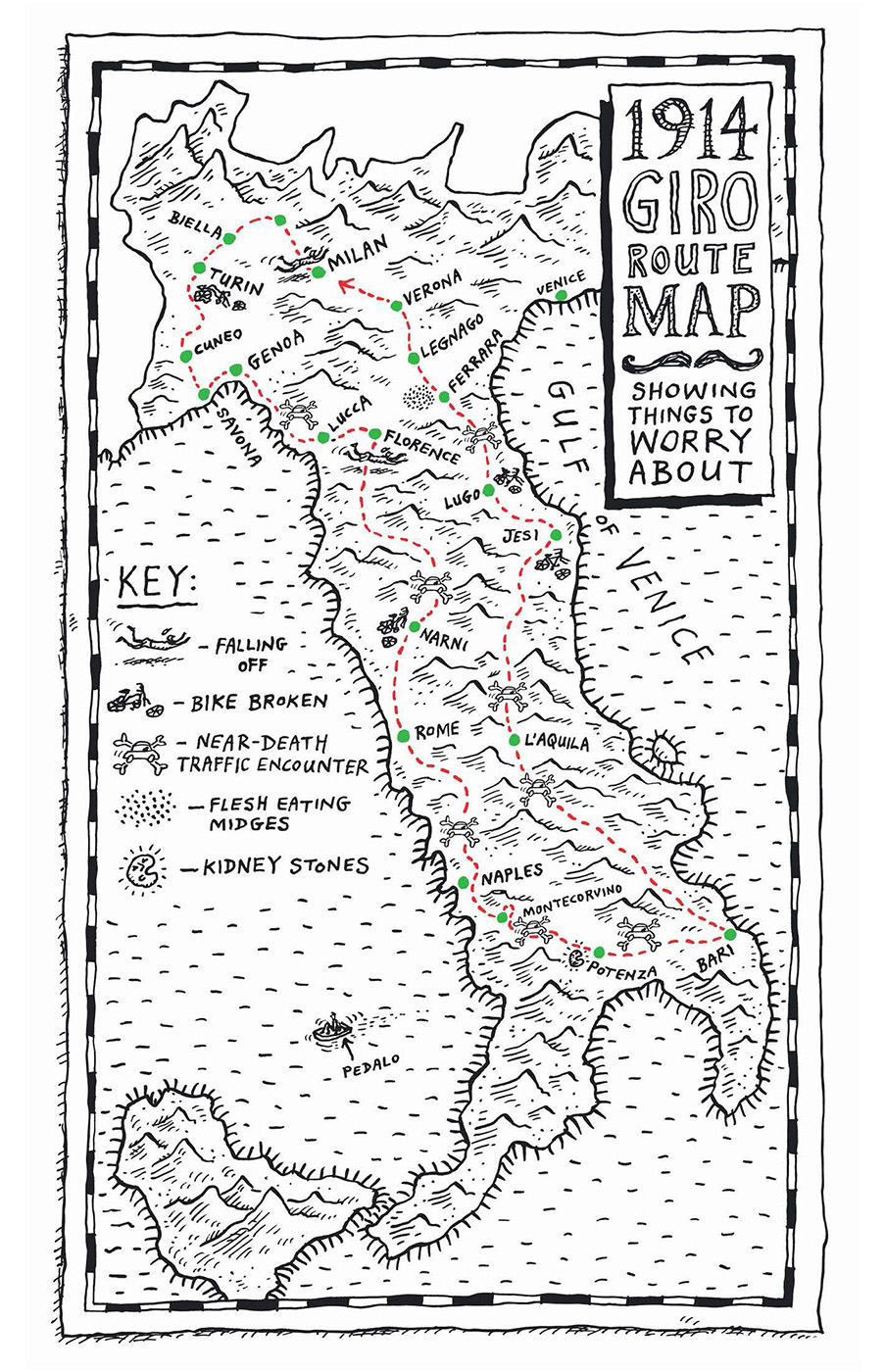

Twelve years after Tim Moore toiled round the route of the Tour de France, he senses his achievement being undermined by the truth about Horrid Lance. His rash response is to take on a fearsome challenge from an age of untarnished heroes: the notorious 1914 Giro dItalia. Historys most appalling bike race was an ordeal of 400-kilometre stages, cataclysmic night storms and relentless sabotage all on a diet of raw eggs and wine. Of the 81 who rolled out of Milan, only eight made it back.

Committed to total authenticity, Tim acquires the ruined husk of a gearless, wooden-wheeled 1914 road bike, some maps and an alarming period outfit topped with a pair of blue-lensed welding goggles.

What unfolds is the tale of one decrepit crock trying to ride another up a thousand lonely hills, then down them with only wine corks for brakes. From the Alps to the Adriatic the pair steadily fall to bits, on an adventure that is by turns bold, beautiful and recklessly incompetent.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Having ridden the route of the Tour de France in French Revolutions, led a donkey on a 500-mile pilgrimage in Spanish Steps and driven round the worst places in Britain in an Austin Maestro for You Are Awful (But I Like You), Tim Moore can look back on a towering career in daft misadventure. Gironimo!, his latest and most imposing pedal-powered endeavour, is a story he will be dining out on for years alone at a table for one. Moore lives in London and still wears those googles at Christmas.

ALSO BY TIM MOORE

French Revolutions

Do Not Pass Go

Spanish Steps

Nul Points

I Believe in Yesterday

You Are Awful (But I Like You)

Thanks to Paolo Facchinetti, Jim Kent, Matthew Lantos, Lance McCormack, Suneil Basu, Thierry, Emile and the other tontons, Fabio at Free-Bike, Paul Ruddle, Matt, Fran and Bethan at Yellow Jersey, C.D. Conelrad and many others at AS, my arse, and my mummy and my daddy.

Gironimo!

Riding the Very Terrible 1914 Tour of Italy

Tim Moore

PROLOGUE

The sun has just slipped behind the lonely Campanian Alps, taking summer with it and surrendering a dishevelled mountain-top lay-by to shadowy, misted silence. Briefly, at least, for an ugly noise now builds from beneath Monte Licinicis final hairpin, the desperate gasps and creaks of aged toil. At length, inching waywardly out of the gloom, comes the ghost of a bike, and hunched over it the ghost of a man. Even in this light the pair are visibly past their ride-by date. The man could, theoretically at least, be a great-grandfather; the bike could have belonged to his. Their geriatric struggle demands sombre respect, but doesnt get it, because the man is wearing a giant Rubettes cap and blue-glassed leather goggles, and when he comes to a squeaky halt in the lay-by his woollen-pouched nuts slam stoutly down onto the crossbar.

As formerly round objects, the mans reproductive organs are not alone in this scene. You now note that his bicycles wheels are rather less circular than is considered traditional, and 100 per cent more wooden. The rear is unencumbered by gears, and keen eyes may spot the words VINI DI CHIANTI printed on the crudely hand-crafted brake blocks. A wise observer hes just behind you might take account of all this, and the rust-mottled frames heft and geometry, to date the machine to the very dawn of competitive endurance racing. That bicycle, he will tell you, is one hundred years old. And that man, you will tell him, has just burst into tears.

Set into the lay-bys rocky retaining wall are two weather-beaten plaques, each honouring a long-gone local cyclist. His unbecoming tears are a tribute to their lives and times, the glorious, brutal age of Fausto Coppi and a generation either side, when those who gave their all in the saddle stood alone as towering national heroes. Hes weeping for them, and for anyone whos ever ridden a bike up a hill too far. Which, predictably enough, means hes really weeping for himself, because it is getting dark and hes a spent force in the unpeopled middle of a mountainous nowhere; because he has never felt so far from home; because he and his ancient steed have both aged twenty years since the distant foot of this mountain; because a largely decorative braking system means he should put his name down for a plaque on that wall of death before the forthcoming descent.

This is a man on the cusp of surrender: he has just emptied himself once too often, and is barely halfway through a ride that a century before decimated a field of braver, better and much, much younger men. All things considered, its just as well that his nuts have by this stage long since been pummelled and battered into a pain-resistant coma, or hed probably still be crying up there now.

CHAPTER 1

YOU HAVE SOME, uh, exprience mcanique with the bicycles?

My questioner smiled at me across a stained garage floor bestrewn with dead and dismembered machines.

A little, I said. You know: un peu.

This was a hard, straight fact, delivered in a deceitful tone of manly understatement. I had driven to a village in Brittanys damp, green fundament to meet this man, whose name was Max, and purchase the mountain of ancient bike bits he had advertised for sale. The trip had involved a dawn ferry and several hours of wet autoroute. I gazed across the jumble of corroded spokes, sprockets, rims and tubing and felt my mind clog with misgivings.

Voil, said Max, picking up a dented tin full of hollow, square-ended brass bolts and handing it to me. Trs importants!

I weighed it with a knowing smile, thinking: What in the name of crap are these? More generally, why have I gone to all this trouble for the privilege of filling my car and then my family home with rusty artefacts of largely unknown purpose? Above all, how had I come so far without considering, even once, the ludicrous enormity of the task I had set myself?

The hands that held this tin had not attempted such an overwhelming technical challenge since the Airfix age. The legs beginning to tremble on Maxs oil-blotted concrete had last been put to sustained athletic use twelve years previously. Yet somehow I expected to employ these appendages first to assemble a functioning bicycle from the century-old components piled up before me, then ride it around the 3,162km route of the toughest race in history.

I passed the tin back to Max and asked him where his toilet was.

The journey that led me to this Breton garage had started sixty mornings earlier, when I opened the inside back page of my paper and read that US federal prosecutors were dropping a two-year investigation into allegations of systematic doping by Lance Armstrong and his former team, US Postal. The article ended with a quote from the worlds best known and my least favourite cyclist, muted by his usual pugnacious standards but still enough to pepper the insides of my cheeks with angrily shattered fragments of Bran Flake. It is the right decision, and I commend them for reaching it.

Next page