To cyclings other prisoners of the road those colleagues whose enduring if occasionally gallows humour, linguistic excellence, radical driving, insatiable thirst for cycling talk and ability to function without sleep make the impossible job of covering a Grand Tour one of lifes great pleasures.

CONTENTS

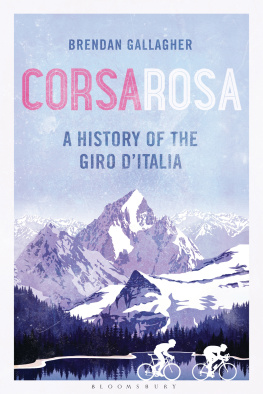

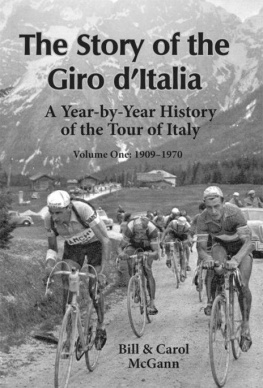

The Giro dItalia may have been created in the image of the Tour de France but it very quickly created its own identity and unique style and its own heroes. The fact that it stands full comparison with the Tour, the worlds biggest annual sporting event, serves only to underline what an extraordinary bike race and sporting spectacle it has become in its own right.

Colder, steeper, often higher, snowier, wetter, foggier, muddier, dustier and yet often more colourful than the Tour, the Giro can also be noisier, harder, friendlier and arguably more beautiful. With the Italian love of drama and intrigue, it has also witnessed more than its fair share of low-life cheating, skulduggery and rank unsportsmanlike behaviour in the ruthless pursuit of glory, fame and financial gain.

Historically the Giro has usually started in late April or the first week of May. Barely a month separates the end of the Giro and the start of the Tour these days and increasingly the dramatis personae are very different, with few GC riders now attempting the double. Its early season slot sets the tone, with the weather as uncertain as the riders form, and the elements can play a massive part in the narrative of the race particularly in the Dolomites and the Alps. The possible wintry condition of those big climbs, and therefore their scheduling as late as possible in the race, also ensures that the Giro builds to a natural crescendo in the last four or five days. Yet the rest of the Italian peninsula is so rugged and hilly that the decisive move or break can occur at any time.

The media interest and hype in the Giro is considerable, and following it can be a chaotic but more informal and intimate experience than the Tour. The crowds are often huge particularly in the city finishes and mountaintops and the tifosi are perhaps the most knowledgeable and passionate fans in the sport. Like them, we should appreciate the enormous challenge the riders face each year in this most brutal and beautiful of all cyclings contests.

Brendan Gallagher

April 2017

The origins of the Giro dItalia are not difficult to discern. A young nation, increasingly obsessed with the bike both as a means of transport and recreation, looked over the border and enviously viewed the growing success story that was the Tour de France. Italy badly wanted the same for itself and shamelessly copied the idea and basic format. The Giro may have very quickly established its own identity and narrative gloriously so in fact and buried deep within its origins there are undoubtedly other much nobler elements but the first edition in 1909 was a commercially driven carbon copy of the Tour de France. The two great races share the same DNA, tapping into the growing mania for cycling. Both were also instigated by harassed newspaper executives looking for an irresistible long-running story to boost circulation and advertising in order to stave off bankruptcy, preferably killing off the opposition in the process. The financial imperative underpinned everything even if the main selling point was the romanticism of the challenge and the heroism and individual stories of those involved.

In France the megalomaniac who was Henry Desgrange seized the opportunity offered by the suggestion of a Tour de France and fashioned a race in his own extraordinary image. A considerable cyclist himself he was an early holder of the Hour record in 1893 Desgrange was fascinated by the ultimate challenge of circumnavigating France and pushing man to the limit, but as sports editor of LAuto what he wanted most of all was to start making money and see off his main rival Le Vlo . The successful running of the 1903 Tour de France killed two birds with one stone in this respect and, although there were tough years ahead, the Tour was up and running. Meanwhile in Italy a similar scenario was unfolding . La Gazzetta dello Sport was the Italian equivalent of LAuto , a sports-orientated cycling-friendly newspaper that was frankly struggling a bit. It had tried various wheezes such as printing on yellow and then green paper and had eventually settled, in 1898, on a rather distinctive pink. Founded on Aprils Fool Day 1896 just ahead of the first of the modern-day Olympics in Athens, it published twice a week, first on Friday to carry features and preview the weekends events and then on Monday to bring news of everything that had unfolded.

In its first year Gazzetta had merged with the specialist cycling paper Il Ciclista e La Tripletta and had been quick to embrace the relatively new sport of cycling. The newspapers cycling correspondent Armando Cougnet, who had joined the newspaper as a wet-behind-the-ears 18-year-old in 1898, had been despatched to France to cover both the 1906 and 1907 Tours and had distinguished himself with his thrilling accounts although there was no particular Italian angle to report. He was, however, in the ideal position to observe how such a monumental stage race had developed and was organised logistically. The newspapers hands-on involvement in cycling had started in 1905 when it organised the Giro di Lombardia and continued apace in 1907 with the soon to be famous MilanSan Remo one-day classic which, curiously, morphed out of a race for motor cars the previous year. That 1906 car race produced just two finishers but the vanity of the towns mayor had been tickled and he was soon persuaded to help sponsor a bike race from Milan to the Mediterranean resort town.

Testing the human body and spirit to the limit, along with developing technology, was a big theme in the first decade of the twentieth century and it perhaps helps to see cycling in that context. In 1907 the PekingParis motor-car race was established while 1908 saw the Arctic expeditions of Robert Peary and Frederick Cook and the Antarctic Nimrod expedition of Ernest Shackleton, who trekked to within 97.5 miles of the South Pole. Also in 1908 aviator Wilbur Wright who ran a bicycle repair company with his brother Orville called the Wright Bicycle Exchange entertained invited French guests with a series of short flights around a field near Le Mans, while the following year French aviator Louis Blriot became the first man to cross the English Channel in a heavier than air aircraft. Everywhere pioneers were pushing the limits and the boundaries. The 1908 Olympics in London underlined this, being organised on a grand scale, and there was a significant leap in human performance in virtually all disciplines. One of the most noteworthy, headline-grabbing, performances of those Games came from the diminutive Dorando Pietri from Carpi in Italy who won the hearts of the sporting world for his brave efforts in the marathon when, having seemingly run the opposition to a standstill, he himself started to crack with the finish in sight at the White City Stadium. The distressed Pietri collapsed a number of times and at one stage started running in the wrong direction before being helped through the tape by officials, an act which led to his disqualification. Pietri was denied his gold medal but became a big celebrity in Italy and earned over 200,000 lire as a professional in the next three years before retiring to run a hotel in San Remo.