The Explorer King: Adventure, Science, and the Great Diamond Hoax

Clarence King in the Old West

A Certain Somewhere: Writers on the Places They Remember (editor)

Copyright 2013 by Robert Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury USA, 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Wilson, Robert, 1951 February 21

Mathew Brady: portraits of a nation / Robert Wilson.First U.S. edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-1-62040-204-7

1. Brady, Mathew B., approximately 1823 1896. 2. Photographers

United StatesBiography. 3. United StatesHistoryCivil War,

18611865Photography. I. Title.

TR140.B7W55 2013

770.92dc23

[B]

2013016928

First U.S. edition 2013

Electronic edition published in August 2013

www.bloomsbury.com

For Martha, Matt, Cole, and Sam

Mr. B is a capital artist, and deserves every encouragement. His pictures possess a peculiar life-likeness and air of resemblance not often found in works of this sort.

Walt Whitman, 1846

Introduction

Photo by Brady

In the first decades after the invention of photography, the sun was often credited as the author of a photograph. Sunlight was required to expose the metal plates on which images were fixed in daguerreotype, the first widely used photographic process in the United States, and the sun was necessary in all the processes that followed until artificial light came into wide use in the 1880s. Adequate lighting was so crucial during the early days of photography, given the state of the lenses and chemistry involved, that photographs could not be made on cloudy days, and photographers installed skylights in the roof of their studios to let in more sunlight. In the 1840s, writers on both sides of the Atlantic often seriously argued that American daguerreotypes were better than English ones because an American sun shines brighter, as one newspaper writer put it.

The names first given to photographysun drawing, sun pictures, natures pencilsuggest that a photograph was something created mechanically, scientifically, objectively. Nature, in the form of sunlight, pushed the pencil that drew the image. No artistindeed, no personwas responsible for the photograph itself, which was a precise representation of what the lens of the camera faced. Even a man as sophisticated as Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing in the early 1860s, titled two influential articles he wrote about photography Sun-Painting and Sun-Sculpture and Doings of the Sunbeam.

This idea of photographys objectivity seems nave today. The camera itself does not have a point of view, of course; its only when a person uses the camera to take a picture that it becomes something more than the sunbeams doing. The question of whether photography is an art form was settled long ago, and yet we often think about the photographers in these first decades of the mediums existence, and the photographs they made, as being if not objective then somehow artless; or, at the very best, we think of their makers as bloodless documentarians.

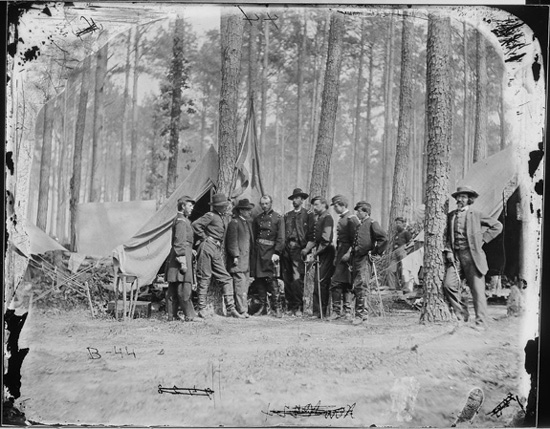

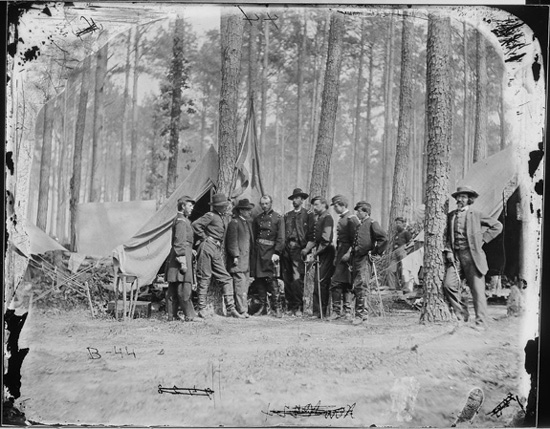

But consider an 1864 photograph by Mathew B. Brady in which he himself appears to the side of a Union general and his staff. Brady had been in the photography business for twenty years on the warm June day when this photograph was taken, and he had labored so tirelessly to make his work and his name known to the public that he had become the most famous photographer in the land. His specialty was studio photographyoften of well-known individuals, ranging from the singer Jenny Lind to President Lincoln, or of interesting groups, such as the first official delegation from Japan to visit the United Statesand this is very much a studio photograph taken out of doors. Even the flap of the tent at the left of the image suggests the draperies of the studio. The photograph has been artfully composed. Gen. Robert B. Potters staff officers are arranged around him roughly by height, each of them wearing a hat and turned toward his boss, while Potter is hatless and staring directly into the lens. Brady has posed himself as what he was, not the subject of the photograph but its presiding intelligence, his gaze not at the lens but bisecting the line between the general, who is in the exact middle of the composition, and the camera. Brady is the maker of this photograph as well as being in it.

One of his operators very likely stood beside the camera and drew out a wooden panel covering the glass negative, permitting the exposure; but an intriguing possibility exists, although experts on cameras of the time doubt it, that Brady is operating the camera himself. In his right hand he holds somethingcould it be a device and is that a wire or tube running down his right leg, connecting him to the camera, moving a lens cover or a primitive sort of shutter, exposing the glass negative to the upside-down image carried by the light? Probably not. But even if Brady holds only a switch he has broken off a tree, who can view this image without knowing that its author was not the sun but a person, the well-tailored artist standing confidently to the right of the frame, hand on hip, leg jauntily cocked. What we have here is, without question, a photo by Brady.

Union General Robert B. Potter, his staff, and Mathew Brady (June 1864). U.S. National Archives

That phrase photo by Brady or photograph by Brady appeared regularly in the illustrated papers of the mid-1850s through the 1870s. What it meant was that an image taken by Bradys studio was the basis for an engraving that could be reproduced in the papers, since the direct use of photographs in newspapers did not become common until near the end of the century. Especially during the years of the Civil War, Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper and Harpers Weekly turned repeatedly to Brady for portraits of those in the news, civilian and military leaders alike, and less often but still regularly for outdoor photographs of preparations for battle or of places where battles had occurred. His fame grew in part because of these credits in the papers, credits that gave the impression that Brady knew everyone and had been everywhere.

He was also, like his onetime neighbor Phineas T. Barnum, a master of getting coverage in the press for himself, his studio, and his work, and like Barnum, he made frequent and creative use of advertising in newspapers and other publications. Brady knew early on that promoting himself and his name was good for business, and so, on his first daguerreotypes and his later elegant salt prints, on his ubiquitous cartes de visite and 3-D stereographs, whether sold directly to his customers or distributed by others, his name or the name of the Brady studio was always affixed. He also understood that proximity to celebrity was as good as celebrity itself, and so, early on, he began to photograph presidents and their wives, statesmen, artists, writers, performers. Anyone in the public eye soon submitted to or sought out the mechanical eye of Bradys camera. Not only did he take and distribute these images, but he also hung them on the walls of his studiohis gallery, as he always called it. Over the half century he owned a gallery, he displayed thousands of photographs in this way, and in all those years, he never once credited the sun with taking even a single image.