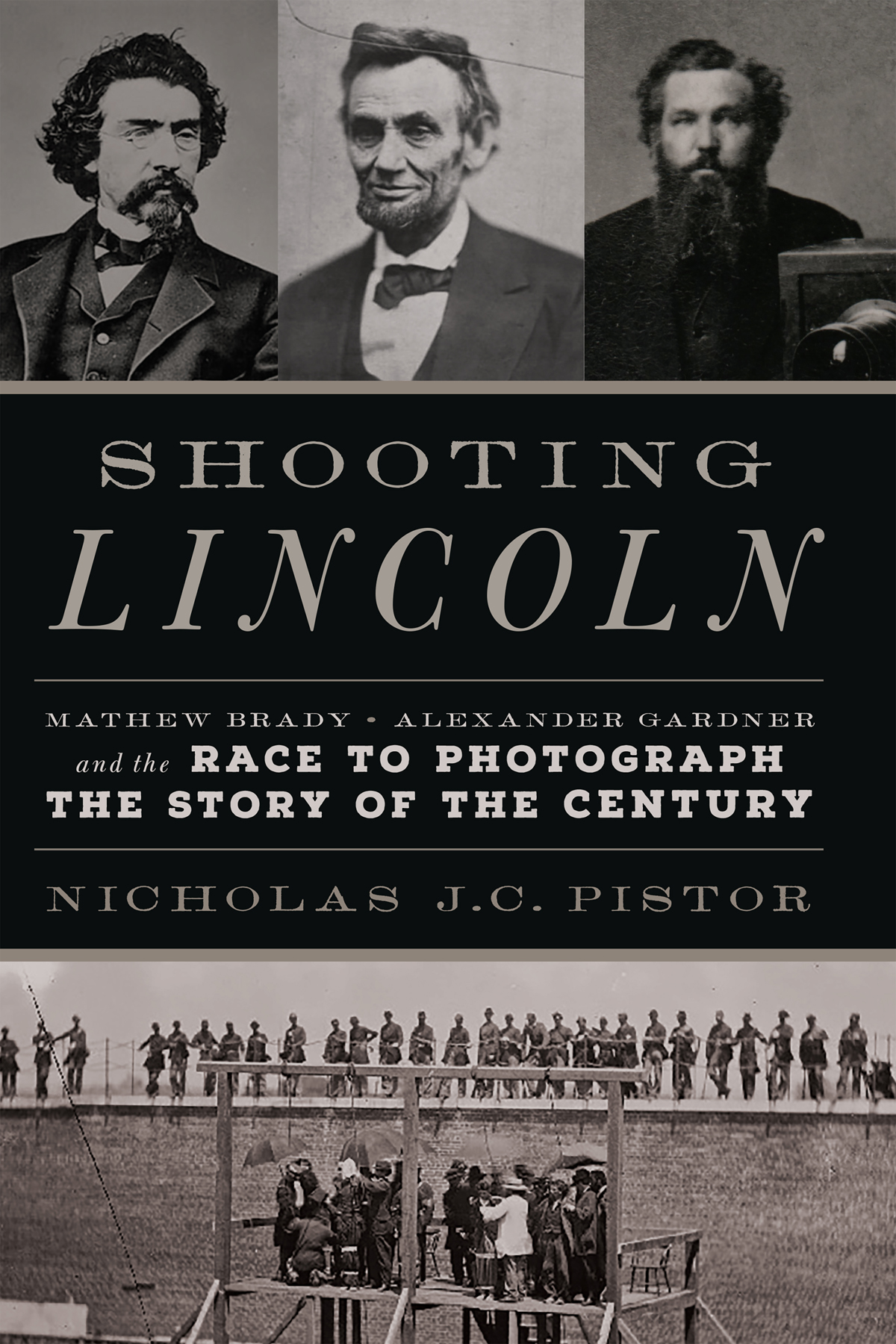

Copyright 2017 by Nicholas J. C. Pistor

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Da Capo Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.dacapopress.com

@DaCapoPress; @DaCapoPR

First Edition: September 2017

Published by Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Print book interior design by Amy Quinn.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pistor, Nicholas J. C., author.

Title: Shooting Lincoln : Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, and the race to photograph the story of the century / Nicholas J. C. Pistor.

Description: First Da Capo Press edition. | Boston, MA : Da Capo Press, 2017.| Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017031093 | ISBN 9780306824692 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780306824708 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Assassination. | Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865AssassinationPress coverage. | Brady, Mathew B., approximately 18231896. | Gardner, Alexander, 18211882. | PhotojournalistsUnited StatesHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC E457.5 .P57 2017 | DDC 973.7092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017031093

ISBNs: 978-0-306-82469-2 (hardcover), 978-0-306-82470-8 (ebook)

E3-20170724-JV-NF

For reporters and photographers everywhere

T HE PRESIDENT LOOKED like he was already dead.

The bags under his eyes resembled the piles of bodies stacked on Civil War battlefields across the North and South. His face was sunken. His lanky frame looked downright skeletal. His wiry salt-and-pepper hair jutted from his head in a tangled messuntouched by a comb from yet another restless night. His wrinkles crisscrossed deep in every direction, offering a reminder that Abraham Lincoln wore the scars of war on his rugged rail-splitter flesh.

This was not a good day for Lincoln to get shot. The Confederates were on the run. The air was filled with the whiff of surrender. The busy president, not yet into his second term, had unfinished business. But there he was, seated on a Queen Annestyle chair under a skylight in the direct aim of Alexander Gardner. Lincolns mischievous eleven-year-old son, Tad, rustled about nearby.

Washington was in a cold snap. A snowstorm was on the way. Time stood still. The quiet was broken only by the clang of church bellstwo dings noting it was two oclock in the afternoon.

Gardner, a burly Scottish immigrant with a wild beard, didnt have a gun trained on Lincolns cavernous face. He had a wooden box with a glass lens, which required Lincoln to be still. He was conducting a photo shoot of the wartime president at his upstairs studio at Seventh and D Streets in Washington, a few blocks from the White House. Outside, men around the country dreamed about making it Lincolns lastand at least one was preparing to make sure of it.

Assassination attempts werent new to Lincoln. He had lived with the threats ever since he was elected. In Baltimore he narrowly avoided an attack years earlier while taking a train to his inauguration. At the moment, though, Lincoln was more concerned with ending the war he had overseen since 1861. The president was traveling throughout Washington with little security. A few months before, Ward Hill Lamon, the marshal of the District of Columbia, scolded Lincoln for slipping out to a local theater without protection. I regret that you do not appreciate what I have repeatedly said to you in regard to proper police arrangements connected with your household and your own personal safety, Lamon wrote. You are in danger. And you know, or ought to know, that your life is sought after, and will be taken unless you and your friends are cautious; for you have many enemies within our lines.

The days and months ahead would be shrouded in myth, talked about and investigated by researchers for the next century and more. But one thing was obvious right then and there. The president was careless about his personal safety. And the man who pioneered the use of photographs to develop his political persona cared even less about how he looked.

A S G ARDNER DIRECTED Lincoln in different poses, John Wilkes Booth, a famous actor, was working on his conspiracy. For the moment, he had settled on capturing Lincolnnot shooting him. Possibly at the nearby Fords Theatre.

Booth knew the theater well. He had stood on its stage sixteen days earlier in a performance of William Shakespeares Romeo and Juliet. The handsome, baby-faced Booth played Romeo. A few days before, he was at the theater, eyeing its exits and pathways for a potential abduction of Lincoln, a fan of comedies and a known guest of the place. John Sleeper Clarke, Booths brother-in-law and famed American comedian, was performing the play The Rivals at the theater the following day. Perhaps Lincoln would show.

The twenty-six-year-old Booth wasnt the type one expected to plan a political coup. He was from a famous theatrical family. His brother Edwin, also a famous Shakespearean actor, once saved Lincolns son from getting hit by a train. When Edwin scooped him off the train platform, the son, Robert Todd, recognized Edwins face from pictures he had seen.

But John Wilkes Booth was not like his brother. While he was an accomplished actor, he was also a drunken Confederate sympathizer who despised Lincoln. At the moment, the public saw otherwise. As earned by his Romeo, we hasten to add our laurel to the wreath which the young actor deservedly wears; to offer him our congratulations, and to say to him that he is of the blood royala very prince of the blooda lineal descendant of the true monarch, his sire, who ranks with the Napoleons of the stage, a critic for the Washington Daily National Intelligencer wrote. We have never seen a Romeo bearing any near comparison with the acting of Booth on Friday night.

Booths own life was headed for tragedy, just like the Shakespeare plays he headlined. Despite outward appearances, he was broke and angered by Lincolns continued prosecution of the war. The Confederacy was in its darkest days. The end was near. General William Tecumseh Sherman had wasted Georgia and was lurching north through South Carolina, the jewel of the rebellion. Lincoln and his cabinet were starting to focus on how to put the fractured country back together again. Since the South couldnt handle Lincoln in battle, Booth figured he had to do it himself.

Booth lived on and off at the National Hotel, a place popular with Southerners in a city built at the crossroads of North and South. The hotel, a series of six connected townhouses, was a Washington landmark that housed all the greats, from Lincoln to Dickens. People quickly panicked.

The newspapers didnt help. The scandal-loving reporters offered detailed accounts of hotel guests who grew sick during their stays. Several posited that the illness was attributable to poisoned rats that died in a water reservoir. Just about any rumor or theory made it into print. The