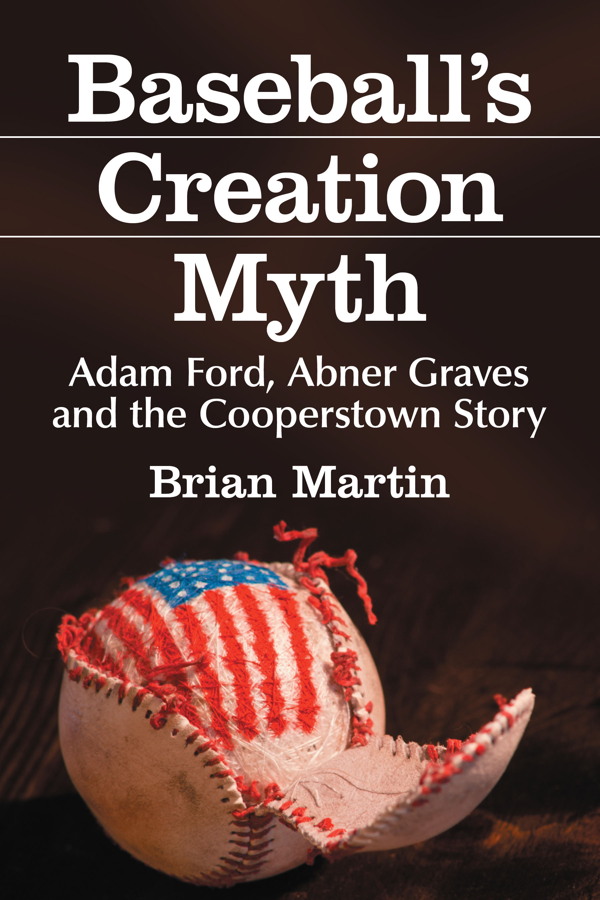

Baseballs Creation Myth

Adam Ford, Abner Graves and the Cooperstown Story

Brian Martin

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0206-6

2013 Brian Martin. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover baseball image (iStockphoto/Thinkstock)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To my wife, Kay,

and our sport-loving kids,

Lindsey and Scott

Preface

This book may make some ball fans a bit uncomfortable.

It looks at an old story with new eyes, a new perspective, and it draws a conclusion that may upset baseball traditionalists.

Baseball is a game that is near and dear to many of us. We are possessive about it, having spent so much time playing it, reading about it and watching it. Baseball is like an old friend. So anyone who introduces new evidence about its fundamental underpinnings is bound to meet resistance. The game has a long history in North America, research clearly shows. Some Americans may be surprised at the reference to North America. The game is known as Americas national pastime, not North Americas, after all. But the fact is, simple ball-and-bat games were brought to the new republic and to the British colonies north of it in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by settlers from England. Those games were rened, developed regional differences and ultimately morphed into the game of baseball we know today.

A parallel pastime has evolved with baseball over the years: the unending search for its origins. Like anthropologists seeking the roots of civilization, the baseball community has been xated on determining who invented the modern game, when, and where. Accepting it as an evolution of bat-and-ball games played by English children has been difcult, if not impossible, for some Americans to accept.

A bit more than one hundred years ago, Albert Goodwill Spalding settled the issue, in his own words, for all time, in his book Americas National Game. The former star pitcher, owner of the Chicago White Stockings, president of the National League and head of the Spalding Sporting Goods empire wrote that baseball captured and reected all the best qualities of America and Americans. He noted that a special commission (which he himself established) had traced the origins of the game to a small village in New York state where a military man invented it. Spalding asserted that it couldnt have been the product of the English, whose preferred game was cricket, he wrote, because cricket is easy and does not overtax their energy or their thought.

Spalding was not the rst, nor the last, to wrap baseball in Old Glory. The result has been that most Americans accept the game as American property. To this day, a surprising number still believe the myth promoted by Spalding that it was invented in Cooperstown by Civil War hero Abner Doubleday. Baseballs creation myth is powerful and durable and it has believers in unexpected places. For these true believers, contrary evidence amounts to sacrilege, so they choose to ignore it. They may not realize the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown no longer makes the claim that the game was invented there in back in 1839. More than enough evidence has emerged since the shrine to baseball opened (and even before that) to prove beyond a reasonable doubt the game did not begin there.

Baseball is a game that grew in popularity in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, especially in the United States, which was undergoing a fundamental and profound change. An agrarian society was being transformed into an industrial one with the migrations of millions from the farm to the city. Baseball, with its pastoral connotations, harkened back to simpler days and gave urban dwellers something to cheer for, especially when for so many of them there was so little cheer in their circumstances. A day at the ball parka term that was coined latercame as a welcome relief from six days in a factory.

It is not all that well known that the game also had a long history north of the border in the British colonies of Upper Canada and Lower Canada, renamed Ontario and Quebec when those colonies federated with Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in 1867 under the name Canada. The same immigrants who brought the game to America brought it to the British colonies. Some of them were literally the same immigrants, having settled rst in the new republic before moving to the colonies in pursuit of cheaper land or a different political climate. Upper Canada, particularly, adjacent to the states of New York and Pennsylvania, owed much of its early growth and development to newcomers from the republic. Given the much smaller population of the Canadian colonies/provinces and their cities, the professional game was somewhat slower to develop there, although by the 1870s two Ontario cities elded successful professional teams that competed against professional nines from Boston, Chicago, Pittsburgh and elsewhere. In the mid1880s, Spalding tried to persuade Toronto to join the National League.

The story of baseball being invented in Cooperstown was told in 1905 by a man then living in Denver, Colorado, a mining engineer named Abner Graves. No one else had ever made that claim, coming as it did so many years after the alleged event in 1839 that all supposed participants would have been dead or senile. Spalding tried to corroborate it, but failed to do so. Despite that, he embraced the tale and so, ultimately, did America. Somewhat belatedly, Cooperstown did as well. Historians have had a eld day for decades debunking the story once taught to American school kids. Aside from using solid research and real facts to puncture the myth, some have attacked Graves and his character. Yet no comprehensive effort has been made to look into the man and try to determine why he told the story that so totally captured a countrys imagination. Until now. Research for this book took the author to Denver, to Cooperstown and on a path that led to the discovery of the granddaughter of Graves, living in Washington state and in her nineties.

The ndings and conclusions shared in these pages may surprise, perhaps irritate Americarst readers. So be it. But when it comes to the origins of baseball, closed minds have wrought considerable mischief in the past.

This work presents a compelling case that Abner Graves borrowed his story about Cooperstown, or parts of it, changing people and places in order to help Spalding prove an American birth for baseball.

One

A Simple Letter

The two-page typewritten letter was a modest effort. Rife with typographical errors, inappropriate spacing, odd punctuation and inconsistent spelling, it landed on the desk of William B. Baldwin, editor of the daily AkronBeacon Journal, in an envelope bearing the imprint of Akron, Ohios Thuma Hotel.

Dated April 3, 1905, on letterhead from the Bank Block ofce of mining engineer Abner Graves, Denver, Colorado, it appeared to be a carbon copy. Graves, who had signed it, went right to the point:

Next page