This book is dedicated to the notion there is always something we can learn from history.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend heartfelt thanks to the many people who gave of their time to share what they knew about topics covered in this book. Research is so rewarding because, aside from producing much-needed information, it introduces the researcher to many dedicated and helpful guardians of records who invariably bend over backwards to assist. In particular, I would like to acknowledge the help of Shannon Prince, curator of the Buxton National Historic Site and Museum in North Buxton, Ontario, as well as that of Natasha L. Henry, president of the Ontario Black History Society in Toronto. Thanks are also due to Samantha Meredith, executive director and curator of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society and Black Mecca Museum in Chatham, Ontario.

In Niagara-on-the-Lake, historian Doug Phibbs was exceedingly helpful sharing information about the history of that pretty town and some of its noteworthy inhabitants in the past. Also there, writer Denise Ascenzo and Shawn Butts of the Niagara-on-the-Lake Museum were valued partners in research. At the Fort Erie Museum, Jane Davies provided a wealth of historical information.

In South Carolina, Nancy Sambets, director of archives at the History Center of York County in York, kindly provided an important image and information about that town and its characters. Also in York and pitching in to help was Zach Lemhouse, historian and director of the Southern Revolutionary War Institute.

A special shout-out goes to Mark Bourrie, with whom this author once committed daily journalism and who has since become a successful, prolific, and bestselling author. Mark kindly provided advice about connecting with folks who might be interested in publishing this book. Things worked out. Eventually. Thank you, Mark.

Also deserving of praise is dear friend and ancestry researcher Diana Copsey Adams, of Denver, Colorado. Her amazing skills at genealogy and help with several of the authors previous books have earned her the affectionate nickname Sherlocka. In London, Ontario, Joseph ONeil Jr. and Kate ONeil kindly shared what they knew about some of the Southerners resting in a London graveyard. London historian Daniel Brock could always be relied on to fill in blanks in my knowledge as needed. A debt of gratitude is owed to Donald Murray, also of London, a longtime friend of the author whose sage advice and editing skills at the early stages of this book helped make it possible. At a later stage, editor Lesley Erickson provided some excellent ideas to help trim the manuscript, fine-tune it, and reorder some of the content. Thanks, Lesley, for helping me make this the best book possible. At ECW Press, co-publisher Jack David was a pleasure to work with and Samantha Chin demonstrated her heroics with copy issues on several occasions.

Here are others deserving of mention. Apologies are extended to anyone who may have been inadvertently omitted.

Photographer Katie Stewart, of KMS Photography, for her fine images taken in and near her community of York, South Carolina

Miranda Riley, Collections Manager, Royal Military College, Kingston, Ontario

John Aitken, historic postcard collector, Oshawa, Ontario

John Lisowski, historian and lawyer, London, Ontario

Theresa Regnier, Archives Assistant, Regional Room, D.B. Weldon Library, Western University, London, Ontario

Jean Hung, Archives Media Assistant, Collections Centre, Western Libraries, Western University, London, Ontario

Paul Culliton, writer, historian, London, Ontario

Mark Richardson and Arthur McClelland, London Room, London Public Library, London, Ontario

Stephen Harding, friend and historian, London, Ontario

Bob Strawhorn, Civil War buff, Woodstock, Ontario

Scott Andrew Collyer, friend and occupant of a historic home in London long occupied by Southerners, which is featured in this book and whose days are numbered

Introduction

Leafy Woodland Cemetery is the final resting place for many prominent citizens of London, Ontario, including former mayors and business leaders such as the beer-brewing Labatt family. My unexpected discovery of some Americans also interred there was the genesis of this book. Amidst the grand markers for the Labatts and other community leaders can be found a cluster of headstones for some former enslaved people and plantation owners who were born in Charleston, South Carolina, nearly 1,000 miles due south. Why did these Southerners make the long trek to London so long ago? And how is it they rest alongside prominent citizens in a foreign land so far from home?

The grand stones of the South Carolinians stand in stark contrast to the unmarked plot of Shadrach T. Martin, a native of Tennessee who arrived in London in 1854 and became a popular barber. He was the first Black person to enlist with the Union Army shortly after the Civil War broke out, long before colored regiments were formed. Martin served on an army gunboat in the Mississippi River for more than two years before returning to the life he had built in London. A pioneer for his race, he enlisted to fight for freedom for Black people and against a system of servitude that provided such a comfortable life for the Southerners who also lie in Woodland.

The final resting place of others who fought in the Civil War, on both sides, can be found elsewhere in Canada. They include enslaved men and women who sought freedom before the war and other fugitives who had entirely different reasons to find refuge in Americas northern neighbour once the fighting ceased.

Among the Black people who found freedom in Canada was the model for the lead character in Harriet Beecher Stowes powerful anti-slavery book Uncle Toms Cabin. Also making the trek north was the white man who inspired the main character in The Birth of a Nation, a racially charged film that reignited hatred for Black people and led to the establishment of the modern Ku Klux Klan. Canada tolerated, if not welcomed, all comers from both sides of the conflict, reflecting the complex role played by the colony-turned-country in race relations and politics in North America during the years bracketing the Civil War.

Canadas long history of acceptance preceded the war between the states and is well known. Sometimes Canadians find themselves the butt of jokes for being so civil and polite. Robin Williams, the late American comedian, apparently had a soft spot for Canada and made at least two films north of the border. In 2013, a year before his untimely death, Williams expressed his fondness for The Great White North this way: You are the kindest country in the world. You are like a really nice apartment over a meth lab.

Williams easily could have referred to Canada as Americas attic. This book suggests the attic analogy in a bid to explain how Canada acted as a refuge in the years leading up to the Civil War, during the conflict itself, and in its aftermath. When things got out of control in the overheated meth lab, a time-out room was nearby. Conversely, it explains why some Canadians went south to contribute to the war effort on both sides.

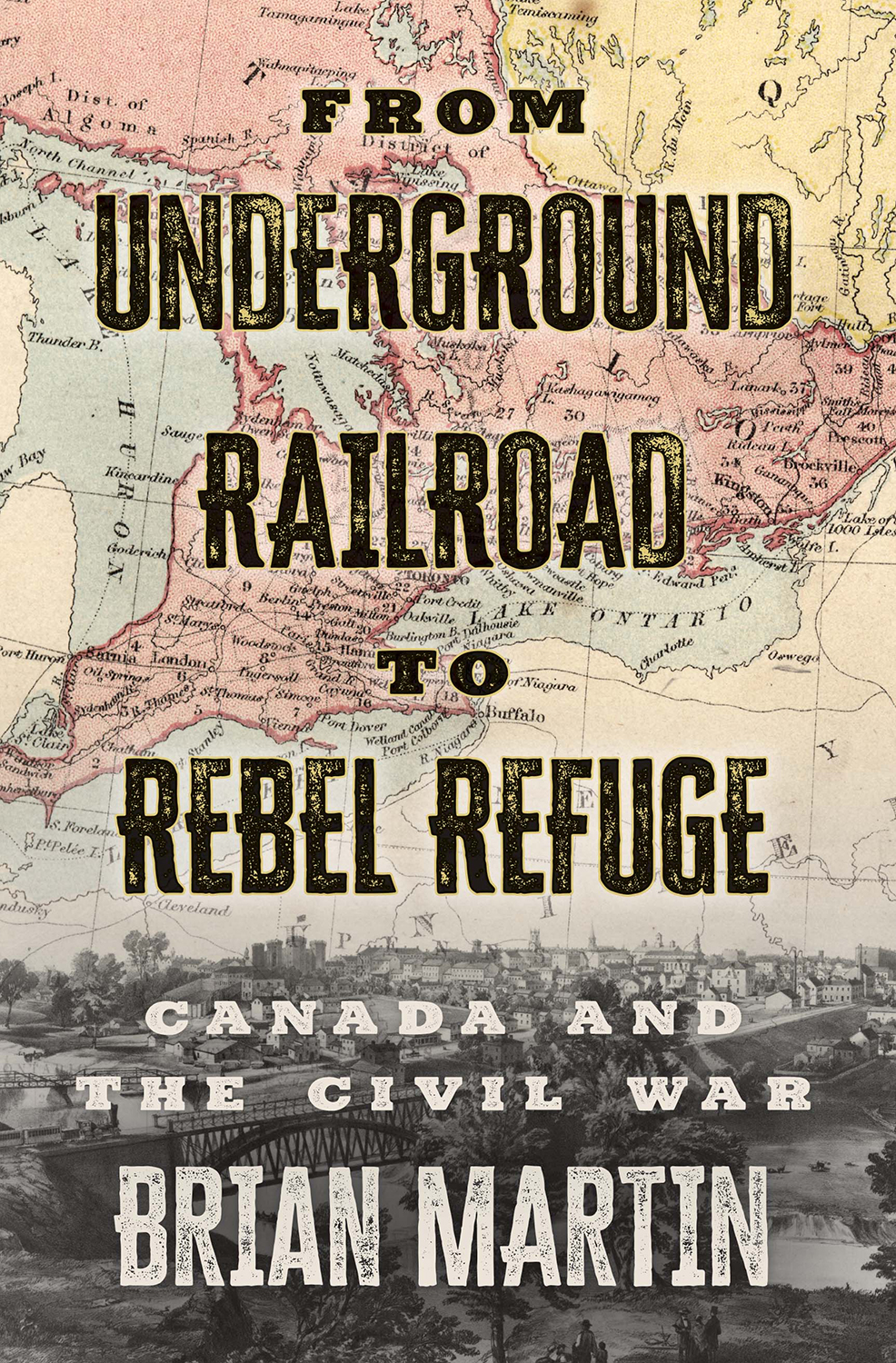

From Underground Railroad to Rebel Refuge tells the story of the flight and history of fugitives from south of the border and how Canadians dealt with them over the course of many decades. Before the conflict, an estimated 40,000 formerly enslaved and free Black people settled in what became Ontario. When the war broke out, some American white men, motivated by money, crossed the border to enlist young Canadians to take up arms in Union blue. In all, about 20,000 men from British North America joined the Union and Confederate armies, some as a result of trickery, but others for their own reasons. Buying agents from both the North and South came north to buy supplies to feed their armies and a large number of horses to move them. There were also American spies and operatives who worked from bases in Toronto and Montreal. Some were funded by large amounts of Confederate money to distract the North with daring missions launched from its back door. They too were tolerated by Canadians, if not welcomed. The border proved porous and many who chose to cross it died in each others country. From their vantage point above the fray that played out below them, Canadians developed sympathies and prejudices in response to events in which they became entangled. An intriguing four-way relationship existed for a time between Canada, the United States, Britain, and the Confederacy, in which Canada (and Britain) developed sympathy for the South and Southerners coupled with distrust, dislike, and fear of the Union. The Civil War helped push Britains North American colonies toward Confederation for fear that victorious Union guns might be directed north to finish a conquest the aggressive young republic failed to accomplish in the War of 1812.