The end of the Underground Railroad line represented freedom, and for that, fugitive slaves were willing to make great sacrifices, face difficult challenges, and take enormous risks.

Thousands of courageous African Americans escaped from slavery in the South along what became known as The Underground Railroad. The railroad provided a secret way to transport slaves to freedom in the Northern states and Canada.

In The Amazing Underground Railroad: Stories in American History, author Kem Knapp Sawyer captures the courage and determination of many fugitives who traveled the Underground Railroad to freedom. Knapp brings to life the dangers faced by escaped slaves and those who helped them along the way. The success of the Underground Railroad shows the resolve of many whites and blacks to end slavery in the United States.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kem Knapp Sawyer is the author of many books for young readers, including Refugees: Seeking a Safe Haven for Enslow Publishers, Inc. She has also written a novel based on the Underground Railroad: Freedom Calls: Journey of a Slave Girl.

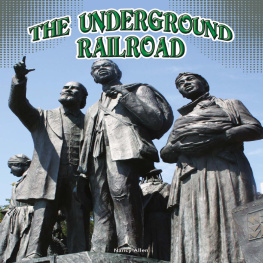

Image Credit: Shutterstock

A view of the Niagara River from the New York side. Once fugitive slaves set foot in Buffalo, they only had to cross the Niagara River to reach Canada and freedom.

The foghorn signaled the impending arrival of the steamboat at the dock in Buffalo, New York. A few minutes later, a loud, grating sound erupted as the crew lowered the plank. The paying passengers gathered their belongings and departed. Little did they know that hidden among them were three fugitives from slavery. Each step the fugitives took along the plank brought them that much closer to their long-sought liberty. Once they set foot in Buffalo, they had only to cross the Niagara River to reach Canada. Although the North offered a measure of freedom to those slaves from the South, Canada promised safety and a new beginning.

The man who had made this opportunity possible was a fugitive named William Wells Brown, who worked as a crew member of a Lake Erie steamboat that ran out of Cleveland, Ohio. It is well known that a great number of fugitives make their escape to Canada, by way of Cleveland, he later wrote.

And while on the lakes, I always made arrangement to carry them on the boat to Buffalo or Detroit and thus effect their escape to the promised land. The friends of the slave, knowing that I would transport them without charge, never failed to have a delegation when the boat arrived at Cleveland. I have sometimes had four or five on board at one time.

William Wells Brown recalled that in 1842, between the first of May and the first of December, he ferried sixty-nine fugitives across the lake, assisting them in completing the last leg of their journey. The fugitives he helped rescue often had been on the road for many weeks. In some cases, months had passed since they had last been under a slave owners command, subject to his every whim, and prisoner to the whip. Most had made some part of their long journey by footthrough woods, across unknown territoryand some had traveled by covered wagon or other conveyance. Few, if any, escaped without help of some kind. Aid came from all quarters in the form of food, shelter, and transportation. Some men and women devoted their lives to this cause, while others simply reached out to a person in need.

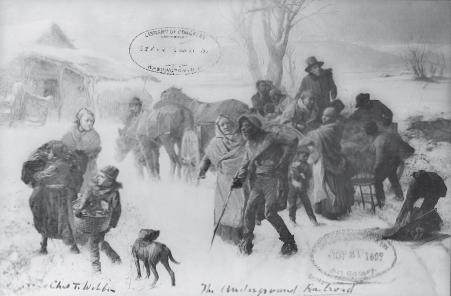

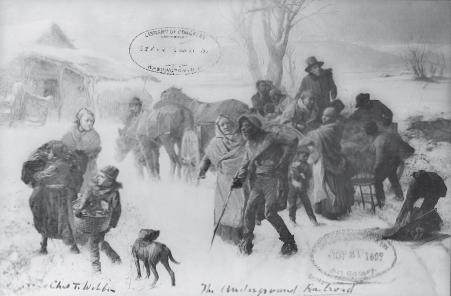

Image Credit: Library of Congress

This is an albumen silver print of the The Underground Railroad, a painting by Charles T. Webber. It depicts fugitive slaves assisted by a group of whites. The reproduction shows two copyright stamps from the Library of Congress, dated 1893.

The system that provided these links between strangers and enabled the slaves to escape was called the Underground Railroad. Beginning in the first part of the nineteenth century, escaped fugitives, as well as other opponents to slavery, found ways to rescue those held in bondage. Some would sneak back to slave territory and serve as guides to free land; others opened their homes to fugitives who needed shelter. All participated in clandestine operations and expanded the increasingly intricate network of the Underground Railroad.

William Wells Brown was born in the early 1800s in Lexington, Kentucky, the son of Elizabeth, a slave, and George Higgins, a white relative of her master. At his birth his mother gave him the one name of William. Before long their master moved to a large farm in Missouri, taking with him the forty slaves he owned. There William worked as a house servant and his mother as a field hand. Once, when his mother arrived at the field ten to fifteen minutes late, she received ten lashes with a whip. William was close enough to hear the whip and later wrote, The cold chills ran over me, and I wept aloud. Later young William was hired out to a Major Freeland in St. Louis, Missouri. Freeland, quick to lose his temper, frequently abused his slaves. One time William ran away into the woods but was chased by bloodhounds and captured. The major flogged him, and then his son smoked himtying him down near a fire of tobacco stems and making him breathe the smoke until he coughed and wheezed and thought he might choke.

For the next several years, William went from one job to another, always earning money to hand over to his master. Once, William was hired out to a Mr. Walker, a slave driveror, as the slaves called him, a soul driver. When they reached New Orleans, William watched as the slaves were placed in a pena fenced yard where they were exhibited and auctioned. William wanted desperately to leave Walkers service, but he had no other recourse. Instead he grew more and more heartsick as he was asked to do increasingly demeaning tasksplucking the gray hairs from old mens whiskers so they would appear younger and attract a higher price.

During the year that William worked for Walker, he made several trips to New Orleans, each time witnessing horrid abuses to the men, women, and children held captive on the boat. At the end of the year, Williams master told him that he would need to sell him. He advised William to go into the city of St. Louis and look for a good master who could purchase him for five hundred dollars. But William made other plans. He gathered some dried beef, crackers, and cheese and left the city at dark, accompanied by his mother. The two found a skiff to carry them across the Mississippi River to Illinois, a free state; then they walked through the woods until day broke. Hoping they would not be captured, they remained in hiding until nightfall when, as William later recalled, we started again on our gloomy way, having no guide but the North Star.

Image Credit: Library of Congress

This image, taken between 1861 and 1869, shows the interior of a slave pen in Alexandria, Virginia. Slave dealers kept slaves in pens before selling them at auction.

They kept walking, even through heavy rain. On the tenth day, they stopped at a farmhouse where the people treated them kindly and gave them provisions. They set out the next morning, but within only a few hours three men on horseback accosted them. These men carried with them a handbill offering a reward for their return. Eager to collect, they captured William and his mother and put them in a wagon. Four days later, they arrived in St. Louis where they were thrown in jail.