Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

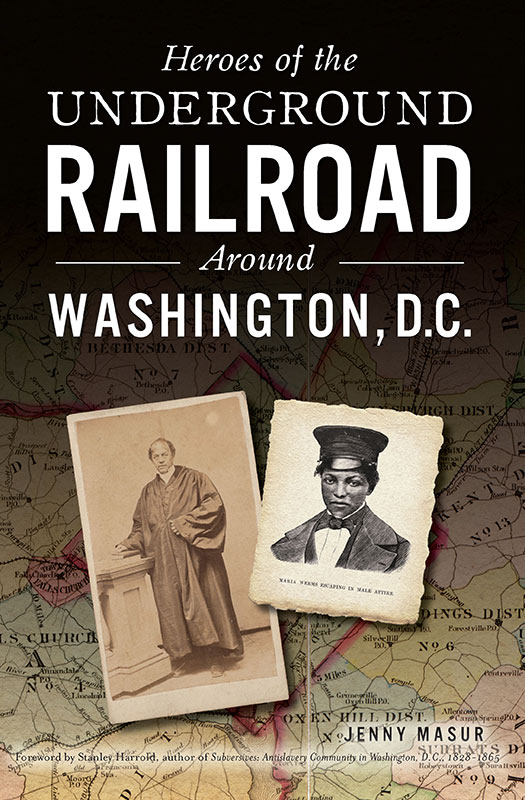

Copyright 2019 by Jenny Masur

All rights reserved

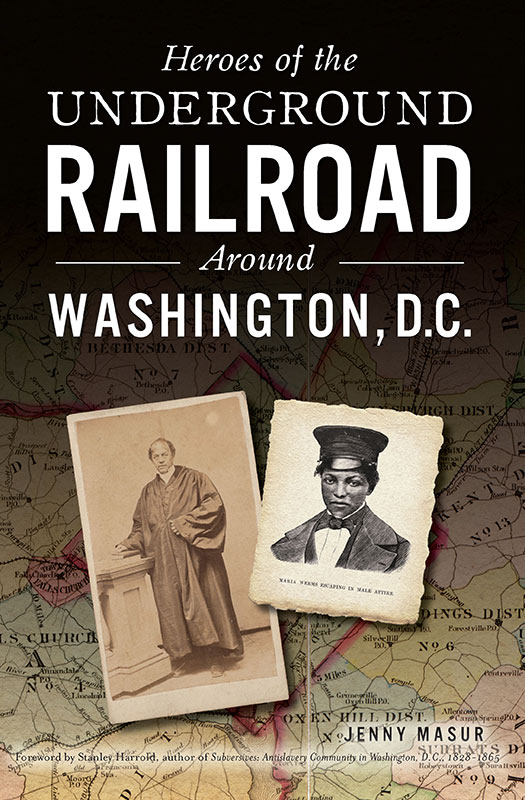

Front cover: Library of Congress; left inset: Library of Congress; right inset: New York Public Library.

First published 2019

e-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.603.6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018959012

print edition ISBN 978.1.62585.975.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To independent and local historians who research the resistance to slavery through flight

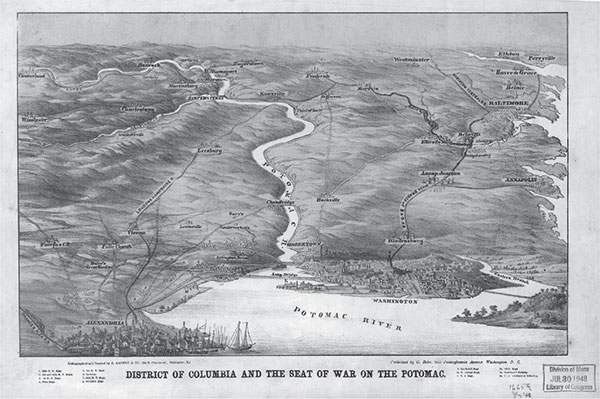

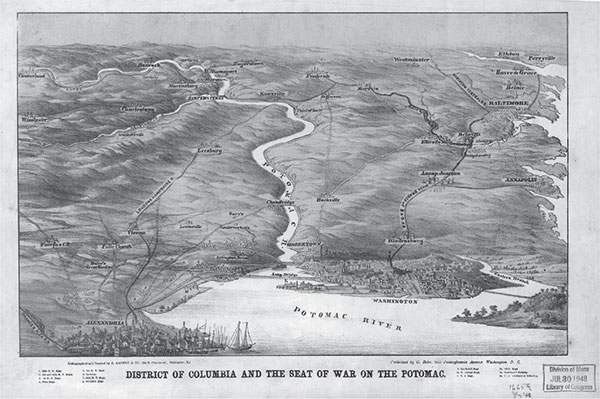

District of Columbia and the Seat of War on the Potomac provides a birds-eye view of the area. Bohn Casimir, E. Sachse & Co. 1861. Library of Congress.

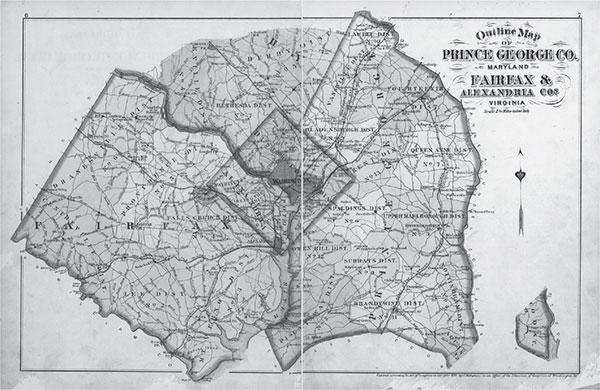

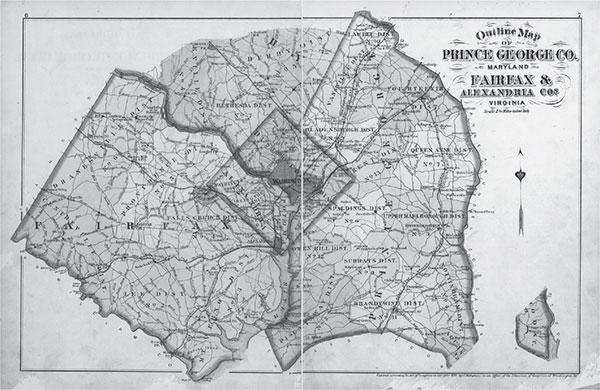

Outline Map of Prince George [sic] Co., Maryland, Fairfax & Alexandria Cos, Virginia, 1878 shows much of the D.C. region. Library of Congress.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

An especially brutal form of slavery, known as chattel slavery, developed in Great Britains North American colonies during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Unlike the forms of slavery that had existed in Africa and Europe since ancient times, chattel slavery reduced those who were enslaved to the legal status of barnyard animals. They had no conventional human rights and could be bought and sold at their owners pleasure. Also, unlike slavery in Africa and Europe, slavery in America was based on race. Only people of African and American Indian descent could legally be held as slaves, and most of them were African Americans.

When in 1776 the Continental Congress declared the United States to be independent of Britain, it also declared that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. When slaveholder Thomas Jefferson wrote these words, however, he meant that only white men were equal and had rights, and other advocates of independence agreed. In the U.S. Constitution, drafted in 1787 by a national convention held in Philadelphia, and in the Bill of Rights, added to the Constitution by amendment in 1791, the same assumption about who had rights remained in force. The Constitution also explicitly supported slavery by providing for the return of slaves who escaped from one state to another, by extending the legality of the Atlantic slave trade for another twenty years and by recognizing the power of the national government to put down revolts in the states.

In contrast to Jefferson, the great majority of the countrys other political leaders, and white Americans in general, a few people, centered in the Northeast, interpreted the Declaration of Independences equal rights doctrine more broadly. Among them were African American leaders and white supporters of a fledgling movement to abolish slavery. Working in separate organizations, these two groups had a major role in bringing about either immediate abolition or gradual abolition of slavery in the northeastern states between 1781 and 1804. In response, Jefferson, James Madison and other southern leaders insisted that the permanent national capital be established on the banks of the Potomac River, which flowed between the slave-labor states of Maryland and Virginia.

Therefore, the creation of the City of Washington in the District of Columbia, cut out of these states and where slavery remained legal, amounted to national recognition of slaverys respectability as well as of the power of slaveholders. Most other western nations abolished slavery in the early 1800s, but the United States retained this oppressive system of unfree labor and race control. South and west of the Ohio River, the government encouraged the systems territorial expansion.

Yet, locating the national capital on the Potomac also gave abolitionists an opening wedge into the slave-labor South. Starting in the 1810s, abolitionists from the North visited Washington to observe the brutality of the citys slave trade and to interact with local African Americans, both slave and free. By the late 1820s, abolitionists had also organized petitioning campaigns designed to raise in Congress the issues of ending slavery and the slave trade in the District of Columbia as well as to encourage debate concerning the morality of slavery. By the mid-1830s, as abolitionists began to demand immediate emancipation of all slaves, lobbyists representing the movement had begun to interact with northern congressman such as John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts. A few of these congressmen were themselves immediate abolitionists. But most often, like Adams, they actively opposed only the existence of slavery in the district, slaverys westward expansion and U.S. annexation of the huge slaveholding Republic of Texas. These congressmens ties to the much more radical abolitionists nevertheless angered their proslavery counterparts and nearly all white residents of the district.

This fraught environment in the national capital is the stage of the individual stories Jenny Masur tells about slaves efforts to gain freedom and about the free people, black and white, who assisted them in their quest. Most of Masurs subjects took action for freedom in Washingtons vicinity, including portions of Maryland and Virginia. Their stories cover a period stretching from the early 1820s to the end of the Civil War in 1865. Some of these stories have been related previously, but in a quite different style from Masurs and without many of the details she provides about individuals backgrounds, desires and emotions. Masur is not interested in general abolitionist and antislavery strategies. Rather, she provides intimate portraits of human beings struggling to escape from slavery and those who took risks to help them reach that goal.

Stanley Harrold, PhD

PREFACE

People commonly associate the names of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman with the Underground Railroad. Frederick Douglass was a freedom seeker from the Eastern Shore of Maryland who became a famous orator and statesman, perhaps the most famous African American leader of the nineteenth century. He was self-educated during slavery and rose to become a renowned lecturer, newspaper editor and autobiographer, as well as recipient of appointments as consul in Haiti and D.C. Marshal. Also from the Eastern Shore, Harriet Tubman is known for her brave escape and her multiple journeys back into slave territory to lead others out of Maryland. Less well known is her later career as Civil War nurse and scout and her role as a humanitarian caring for older African Americans in Auburn, New York. Both figures are commemorated nationally, one by the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in D.C. and the other by Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park in Cambridge, Maryland. Both heroes are celebrated during Black History Month, and there is a Harriet Tubman Day in Maryland.

Next page