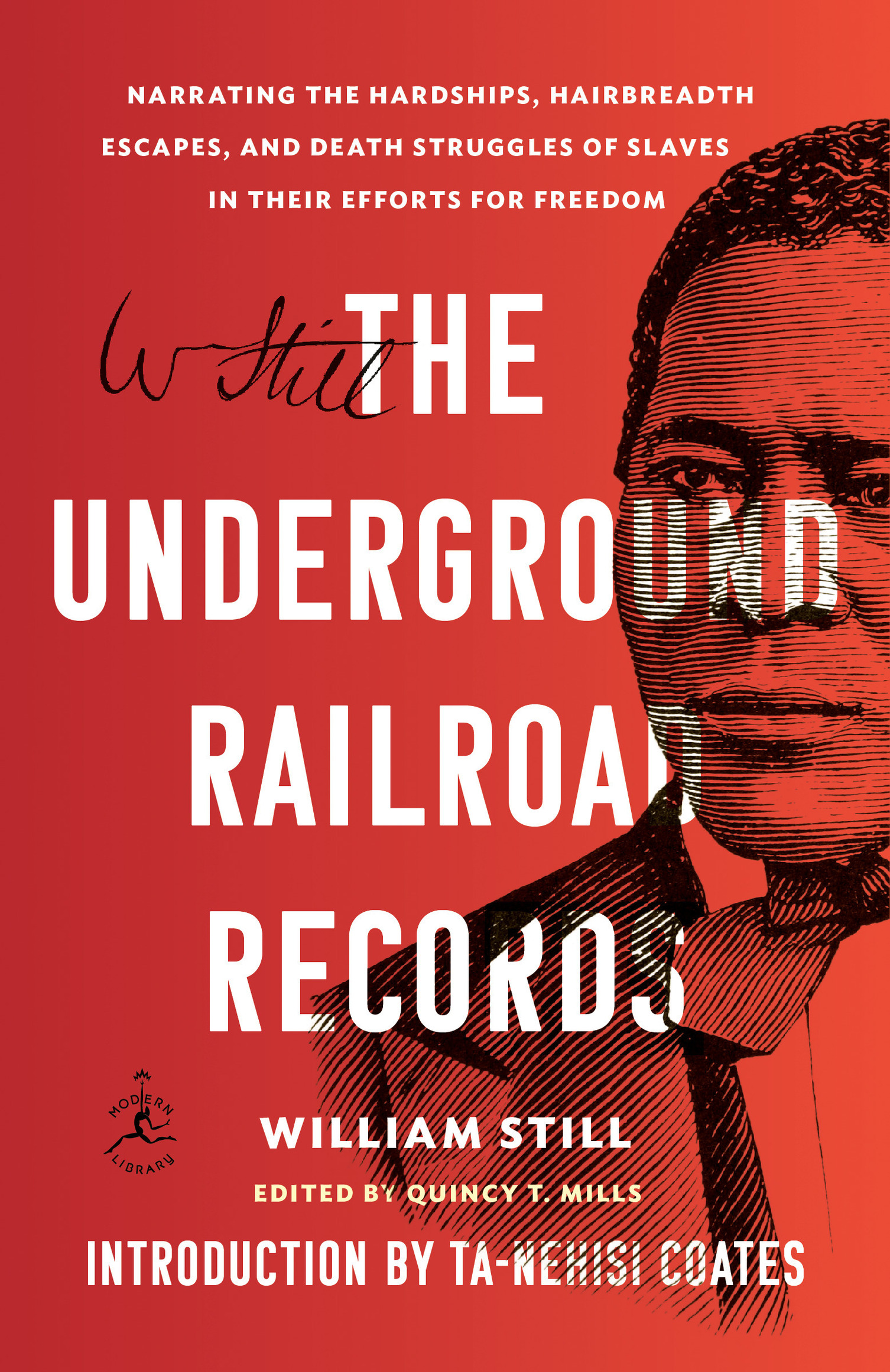

Foreword copyright 2019 by Quincy T. Mills

Introduction 2019 by BCP Literary, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Modern Library, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

M ODERN L IBRARY and the T ORCHBEARER colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

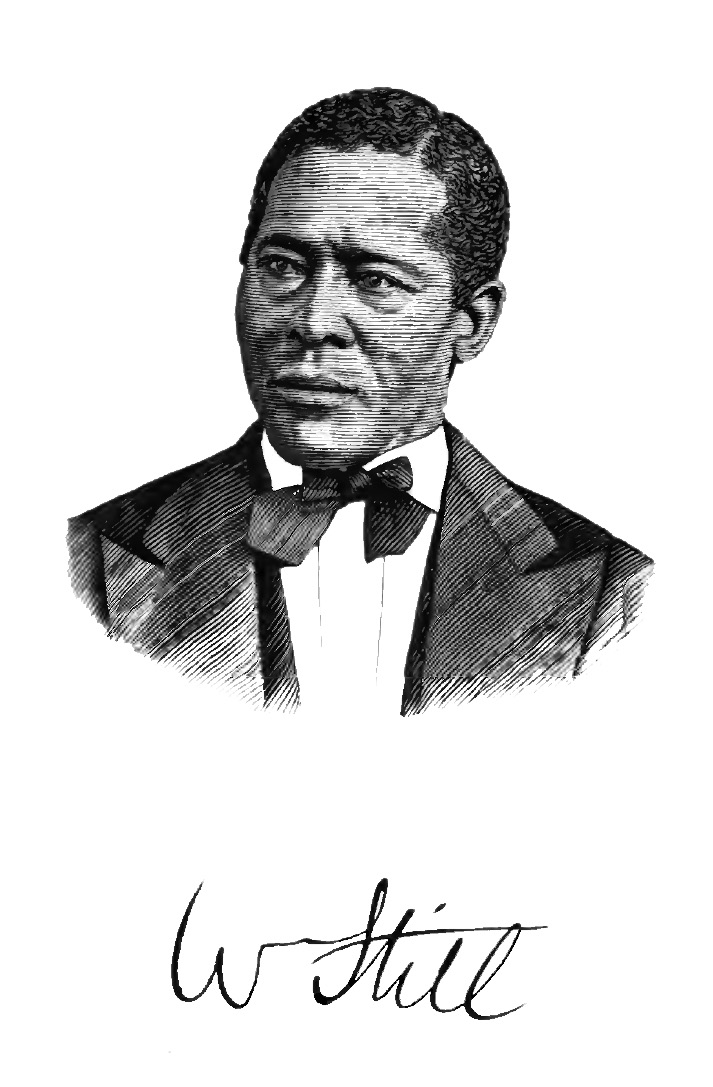

Cover image (portrait and signature of William Still): Boston Athenum, USA/Bridgeman Images

Foreword

William Stills The Underground Railroad Records is a massive testimony of resistance. The Road, as Still would often refer to it, was paved and rugged, choreographed and improvised. Enslaved people shipped themselves in boxes, stowed away in steamships, and stole away the value placed on their labor and bodies as they dressed as men or passed as free to travel north.

Still stood as a historian of fugitivity. An entrepreneur in Philadelphia and, beginning in 1847, a clerk and corresponding secretary of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, he became active in the abolitionist movement. When antislavery activists reorganized the Vigilant Committee into the Vigilance Committee after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Still served as its chairman and coordinated a vast network of antislavery advocates and provided a welcome to many tired souls looking for safe passage anywhere in North America. Still welcomed approximately 649 fugitives and recorded their stories, experiences, and expectations. These records of the Road provide a window onto the paradox of slavery and freedom, and the space between them.

Still first published The Underground Railroad Records in 1872. This and subsequent editions included anecdotes, firsthand accounts, and letters from those escaping slavery and those assisting. Stills archival collection amounted to over eight hundred pages. This present edition has been heavily edited to provide readers access to this significant text. While I have omitted approximately two-thirds of the material, I have privileged the experiences of women and families in this edition.

Historians have written extensively about enslaved men who fled slavery. The assumption was that enslaved women showed up in the advertisements for fugitive slaves less often than men because women were less likely to leave children behind. While this is a misreading of the advertisements, The Underground Railroad Records demonstrates that Black women ran away often, with and without children, husbands, and other family members. They were creative and steadfast in their fight and flight.

As much as this text is about slavery and freedom, it is centrally about family. These accounts, and particularly the letters from fugitives to Still, reveal their longing for those left behind. They wanted Stills help in getting wives, husbands, or children out of slavery or help reuniting them with loved ones who left before them and may have been in hiding. They attempted to reconstitute families as a function of how they understood freedom. Indeed, these are love letters, sorrow songs of ingenuity and hope, and records of visibility from people who needed to remain invisible and out of sight.

I have left the letters from enslaved men and women intact, misspellings and all. As Still himself notes, The originals, however ungrammatically written or erroneously spelt, in their native simplicity possess such beauty and force as corrections and additions could not possibly enhance. While it may take the reader a little time to decipher some words in the text, this minor inconvenience is the least we can endure considering the circumstances and larger historical context in which these letters were written.

Given the time and space constraints, I have omitted a number of accounts and sections of the original text. To be clear, every fugitive, every account, every experience is singularly weighted with the heavy heart and soul of ones journey toward a more free place. In addition to privileging womens experiences, I also sought to include different kinds of journeys from a variety of locations. Although Stills text is also about the work of the Vigilance Committee, I have elected to omit a major section, Portraits and Sketches, that provides short biographies of some of the most famous and active Black and White abolitionists of the nineteenth century. Many of these names, however, show up in the various accounts of fugitives journeys. I accept sole responsibility for any errors or shortcomings in this curated edition.

The stories in this book are gripping, heart-wrenching, and telling of the fortitude of those denied liberty. These are stories of the past, but we should not look past their illuminations on our present. Angela Daviss and Assata Shakurs fugitivity could be appended to this text. The stories of unarmed Black men and women could, too, be appended to this text as many have sought spaces something akin to freedom. Their Road was more modern but no more paved. Stills The Underground Railroad Records paradoxically hides and unveils the practice of freedom.

Q UINCY T . M ILLS

Introduction

When I was a child one of my favorite field trips was from my Baltimore public school to the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian in Washington. What I remember, and what I loved best, was the life-size dioramas of the paststill dramatizations of Neanderthals or watering holes somewhere on the savannah. Even then I was fascinated by historya world that shaped my own, but that I could never visit. The dioramas, three-dimensional reconstructions of the past, were as close as I could ever get. The importance of that key wordreconstructionsI would not learn until much later. The problems inherent to reconstructing the past, the importing of modern prejudice and expectations, were all there in those dioramas depicting, for instance, the first meetings between the pilgrims and the Native Americans. But the inherent problem of reconstruction isnt simply the importing of prejudicethe problem is in its promise that the past is a fixed entity and can be objectively reconstructed. But the truth is that the past can never be fully captured because the past no longer exists. All we have of it are the dramatizations we conjure, the dioramas we construct, the stories we tell.

For most of American history, this countrys historians and mythmakers have favored a particular story of the epic of enslavement and all that came of it. The story comes in two forms. At its most sympathetic, it features heroic whites, joined by pliant and accommodating blacks triumphing over the worst of their bigoted brethren. The recurring vocabulary of this story features a vague love and shapeless hope, which somehow triumphed over a wild and virulent race hatred. In the worse version of the story, these haters are transformed into Arthurian knights, tragically defending an ancient and noble way of life, of which enslavement is but a small part. What each of these stories has in common is the inability to consider the enslaved as the hero of their own epic.