For Jacob

In loving memory of Tim Hetherington: 19702011

Name me someone thats not a parasite, and Ill go out and say a prayer for him.

Bob Dylan

In Afrikaans, the v in vok is soft, and pronounced like an English f; the g in ag is guttural, and to the English ear sounds like the German ach in achtung; the j in ja is pronounced like the y in yes.

CONTENTS

BLACK BEACH

A man is hanging naked from the ceiling by a meat hook. His feet are bound, but his mouth is open screaming a confession. He is surrounded by half a dozen soldiers in ragged uniforms whose fists are caked in his blood. Unsatisfied with his answers, they taunt him in a language he doesnt understand and slam a rifle butt into his testicles. Nine days after the arrests, the most extreme bouts of punishment have begun. The air fills with the bitter-sweet tang of roasting meat. The flames spouting from the soldiers cigarette lighters burn the fat on the soles of his feet until it spits and crackles like a Sunday joint. It is the last thing he will feel. Opened wide by pain, his eyes take in the horror of the blood-spattered chamber hes strung up in and then his heart gives out. His yellow corpse is cut down and stretched out in front of the other prisoners.

Further down the corridor, the interrogations continue. A dim light burns, illuminating a prisoner, half a dozen soldiers and a seated government minister sweating in a smart suit, nodding approval. Next to the minister, behind the soldiers, a man holds a video camera, capturing the scene in minute, digital detail. The pictures reveal the prisoner, silent, hog-tied to a pole, suspended face down. Electrodes are clamped to his genitals, wet rags stuffed into his mouth.

Next door, his comrades lie crying, broken and bleeding, crammed tight into a separate sixty-foot cell with two hundred other prisoners. Baked under a corrugated roof by the relentless sun, they are picked out one by one for interrogation, random beatings or public humiliation. One begs to be shot. Another has his fingers broken.

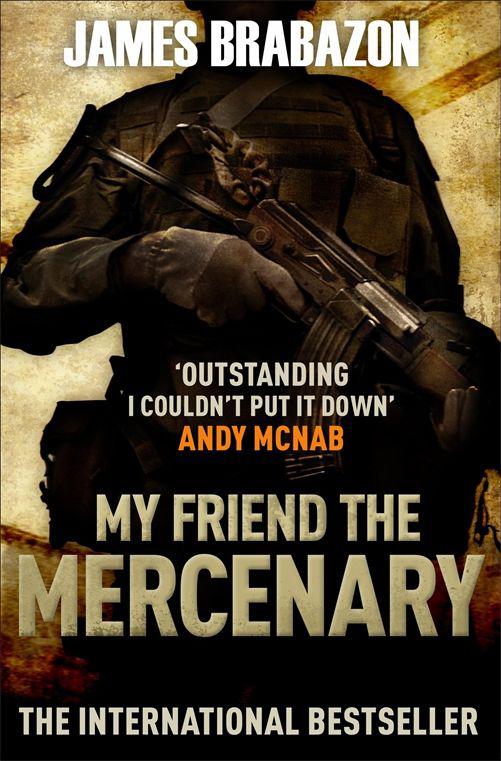

In the last cell a man is screaming on the floor. His hands have been cuffed tightly behind his back. His legs have been pinned at the ankles with shackles, which have been hammered shut by the soldiers. Skin and muscle split as metal bites down to bone. Boots stamp on his feet, ripping out toenails. The prisoners name is Nick du Toit. He is South Africas most notorious mercenary, and one of my best friends.

Nick confessed before this torture began in public, at gunpoint, in accurate, extensive detail, a day after he was seized. Now he no longer knows, nor cares, what he confesses to. His story shifts to fit the fantasies of his jailers, but it is a desperate, pointless game. In this ramshackle collection of wooden huts and concrete cells fenced off from the sea and the world beyond by rolls of barbed wire, Nicks tormentors are not seeking the truth: they want revenge.

Nick is dragged up from the stone floor and forced to kneel. The commander enters the cell and puts a pistol to his head. He has come to execute him, but the gun is empty. Laughing, the guards knock him unconscious with their rifle butts. The same ritual is repeated over and over again.

Nick is left to the mercy of the rats in his tiny, five-by-seven cell. His hands and feet remain chained. Like an animal, he eats scraps of food from the floor, where he must also sleep and defecate. There is no daylight: he is kept in pitch darkness, and beaten daily. And then the septicaemia sets in. Pus oozes from his open wounds sustaining the cockroaches that feast on his sores. By the time he is dragged outside his eyes have sealed shut. The soldiers immerse his head in freezing water and then rip the scabs from his eyes.

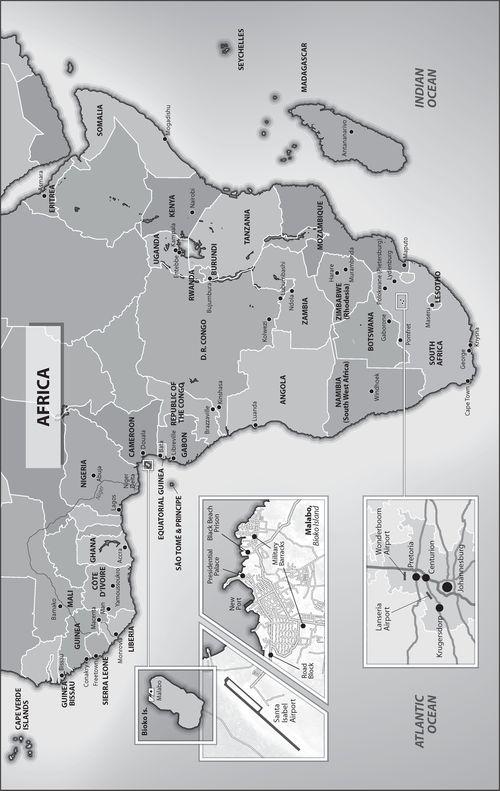

This is how Nick begins his 34-year sentence in Black Beach prison, Africas most notorious jail. He was arrested on 8 March 2004 along with fifteen other men as he tried to overthrow the government of Equatorial Guinea, a tiny West African country fabulously rich in oil. But there is just one person missing from the scene. What Nick doesnt see when he opens his eyes that day is me. Had all gone according to plan, I could have been lying next to him: I was supposed to film the coup.

Treading quickly on the halo of my noon shadow, I skirted the edge of the pool. I glanced at my watch. It was midday on 11 April 2002. I was exactly on time. At a table in the luxury hotel in Johannesburg two white men sat waiting. One, muscular with a ponytail, hid behind a pair of black sunglasses; the other, older and with a neat side-parting, stroked the end of his moustache, scrutinising the terrace and my arrival. I threw out my palm in a premature greeting, and they rose in unison to return it with a gruff Howzit?

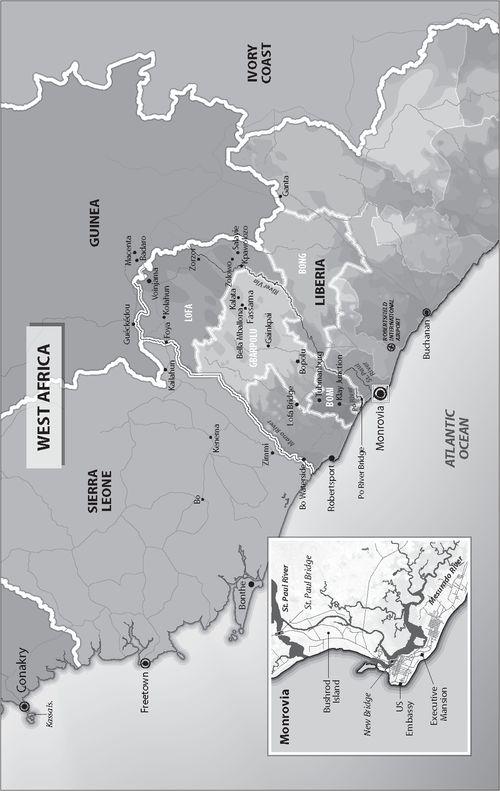

Id met the ponytail in Sierra Leone the year before. A 37-year-old South African former paratrooper and one-time mercenary, Cobus Claassens had fought in the troubled West African state during the mid-nineties with a military company called Executive Outcomes, a private South African-run army which had been hired by the Sierra Leonean president to defeat rebels who threatened to overrun the capital, Freetown.

With the highly trained soldiers of EO on the ground, the rebels were quickly and comprehensively destroyed. Cobus stayed on after his contract wound up, carving out a living from the freelance security contracts that hovered like flies around the carcass of the countrys diamond industry.

He was back in South Africa for a short holiday a chance to see family and chase some business contacts. Id met up with him a few days earlier when a chance conversation had planted an idea for a filming trip in West Africa. It was as preposterous as it was compelling: I would get access to a war in Liberia that no other journalist had filmed, and few even knew was happening. To do so I would need his help, and his man.

I stepped under the shade of the umbrella and saw them clearly.

Cobus spoke first.

This is Nick du Toit. Nick this is James.

His Afrikaner accent bent itself uncomfortably around English vowels. Nick, a plain, forgettable-looking man in his forties, reached over the table, and shook my hand. There was something awkward about him, as if his hands and ears were too big for his body, like a teenager waiting to grow into his skin. I wondered if this was really the soldier that Cobus had in mind. Nicks gaze was alarmingly direct, but not aggressive. He released my hand, sinking his six-foot frame back into the chair. Drinks arrived.

Great to meet you, I said to Nick. Thanks for coming along.

I was struggling to disguise my unease. I was here to recruit a war hero to protect me while I filmed in Liberia. I thought I knew what I needed what I had already been told I would require: a bodyguard; an experienced soldier; someone capable of defending me under fire someone, frankly, extraordinary. Nick looked like none of these things: if anything, his white-and-blue checked shirt, freshly pressed chinos and neat row of pens in his breast pocket made him look profoundly ordinary, like an accountant or mild-mannered manager. Disappointment sagged into my shoulders.

Next page