To Annette, for everything.

Contents

Some had come to see a disaster, others simply for a spectacle, but what they in fact witnessed was the beginning of a revolution. All social strata were represented on the banks of the River Irwell just outside Manchester on that bright morning in July 1761, from the Earl of Stafford down to the humblest farmworker; and all were anticipating a show. The atmosphere amongst them was festive. Bunting decorated the few barges bobbing gently upon the water and a frisson of anticipation sharpened the mood.

A phalanx of stalls had appeared overnight, one of which was offering some kind of roasted meat. As the day settled, occasional gusts of wind started to spread smoke from the fires into the crowd, exciting the taste buds of those who hadnt tasted meat since the previous Sunday, as well as their superiors, most of whom had breakfasted off bacon and fish that morning. Everyone began to wonder if the days events would be over in time for lunch.

There was no set schedule for those events, no printed handbill or official start time. In fact few of those present really knew what to expect. Most were simply enjoying the break from routine and the opportunity to be part of something different. Indeed, it wasnt long before a question mark began to hang over whether anything was going to happen at all. It seemed that the man whose ingenuity and reputation had drawn them all to the river that morning had disappeared.

One man, one common man, who, some said, had managed to trick a peer of the realm into staking his entire fortune on a venture the like of which had never been seen before and most thought preposterous. This venture, this notion, defied all reasonable expectation and even nature itself. One man, a very singular man, insisted everything would be alright. This was to be his moment of truth, but the word beginning to spread amongst the crowd was that he had retired to his bed.

Once sown, this rumour spread quickly, as if it had hitched a ride on the smoke from the fires. As it did so, wry smiles began to spread across the faces of some of the more colourfully and finely dressed of the assembly. Quite reasonably, they began to wonder if rather than coming to witness a challenge to the natural order of things theyd in fact come to see its reaffirmation. This lowly born upstart was to have his comeuppance it seemed. Speeches laced with homage were rapidly being rewritten, with an emphasis on sympathy laced with schadenfreude.

Others, more likely to be dressed in browns and greys, felt the first stirrings of disappointment. Many had come to believe in this man whose exploits in the last few months had earned him the nickname The Schemer. They had already seen him perform marvels and they had begun to wonder if he might, just might, be about to deliver a miracle. They had bought into his dream of a new way of doing things and many had broken their backs for him making that dream a reality. More to the point, many of those looking for this miracle to happen were still owed wages.

By the end of the day everyone in the crowd would have their opinions and prejudices thoroughly tested, and debate on the merits of the missing man would be vociferous in the local inns. When they did finally get to eat that day, some sampled the sweet taste of success whilst others tucked into unseasoned slices of humble pie.

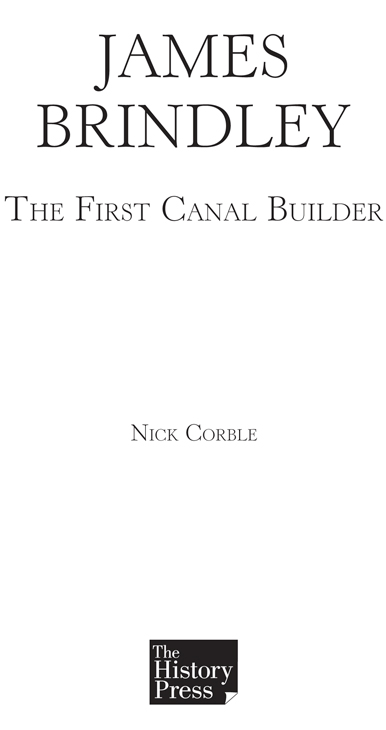

The man they would be talking about was James Brindley, the barely literate oldest son of an insignificant Staffordshire crofter; to some a mere millwright, to others an inspiration. We dont know for certain if Brindley did actually witness the events of that day, but his physical presence turned out to be immaterial. What we do know is that what followed turned out to be a decisive turning point in his life and career, setting in train a sequence of events that was both to make him and, in a relatively short space of time, break him.

But all this was to come. Where might Brindley have been as the stallholders pitched their stakes and the dignitaries gathered on the platform erected especially for the occasion? It is entirely likely that the rumours were true and he had retired to his bed, a habit he often adopted at moments of stress in his life. Its not unreasonable to suspect that Brindley had appreciated the importance of the day and succumbed to an attack of nerves. He was also not immune to bouts of self-doubt, even if these were usually short lived.

A quiet man at the best of times, crowds were not his natural milieu. He had tasted failure a few times in his career, seeing it as a natural part of the learning process, but never had he done so before a specially invited audience of the regional great and good of early Georgian society. However confident he may have been in success, even the faintest prospect of such a public failure was perhaps something best avoided. Equally, his natural introversion may have led him to reject the spotlight in favour of watching events unfold from the sidelines amongst the comfort of his men, observing with a critical eye rather than merely sightseeing.

When the show did finally get underway that warm July morning it took only minutes before Brindleys vision was vindicated and triumph was formally declared, but the crowds lingered for hours, unable it seemed to believe what their eyes had told them, before dispersing along with the last of the daylight. They were only the beginning. Others followed, and over the coming weeks tens of thousands would come and gaze and wonder at the structure before them, transforming the reputation of the man whose inspiration had made it all possible. From a moderately successful local figure, respected as someone who had hauled himself up from very little simply by dint of his skill and inventiveness, he would become a national guru in a whole new field of technology.

Before the year was out the process would begin that, in time, would cement his claim to be the countrys first civil engineering superstar and the progenitor of a new transport system that was to transform the physical, social and economic landscape of the nation. Over the next dozen years he would work tirelessly as the great and good of the newly emerging industrial centres paid homage to his expertise until he eventually died, exhausted by a combination of overwork and undiagnosed diabetes.

Others, often his personal disciples, would soon follow in the path he cleared and within years England would be gripped by a frenzy of activity the consequences of which would define the nations fortunes for succeeding centuries. From a land of simmering potential the country would find a new purpose, as well as the means to realise it, and in doing so become the worlds first global economic and military superpower, with the greatest empire the world had ever seen to prove it.

Before all this there was the little matter of a bridge. No ordinary bridge but a magnificent stone construction with three semi-circular spans, the middle one of which stretched fully sixty-three feet. Together the bridge spanned a total of 200 yards, an unbelievable distance, and was fully twelve yards wide. Like its designer, it was bold and simple in appearance, with no external fripperies there to do a job. The early canal chronicler John Philips later remarked upon the considerable strength of the bridge with every front stone [having] five square faces or beds, well jointed and cramped with iron run in with lead the piers are the largest blocks of stone and camped as before. Also like its designer it had hidden depths and solid foundations.

Perhaps most impressively the bridge was suspended thirty-nine feet over the murky black waters of the River Irwell at a place called Barton, an hours horse ride out from the centre of Manchester. Today, we would pass over such a bridge in our cars without a second glance, but in its day it was a remarkable feat of engineering, made all the more so by the fact that it was not only a bridge but an aqueduct, carrying a self-contained man-made river. Its calm even presence seemed to present a challenge to the more chaotic example nature and God had provided below.

Next page