This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Published by Adlard Coles Nautical

an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

www.adlardcoles.com

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright Stuart Fisher 2015

First published by Adlard Coles Nautical in 2015

ISBN 978-1-4729-1852-9

ePDF 978-1-4729-1854-3

ePub 978-1-4729-1853-6

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is produced using paper that is made from wood grown in managed, sustainable forests. It is natural, renewable and recyclable. The logging and manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Contains material previously published in Canals of Britain 2nd Edition by Stuart Fisher, Adlard Coles Nautical, 2012.

Typeset in Gothic 720

Note: while all reasonable care has been taken in the publication of this book, the publisher takes no responsibility for the use of the methods or products described in the book.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

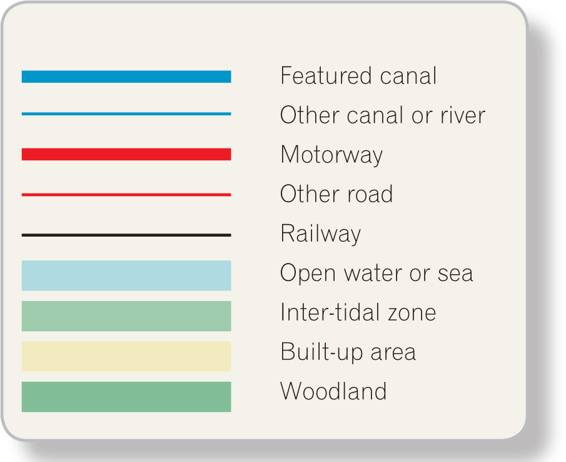

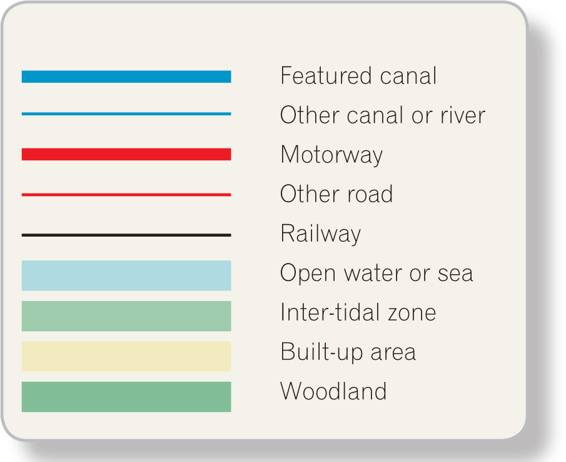

Legend for maps

Contents

Introduction

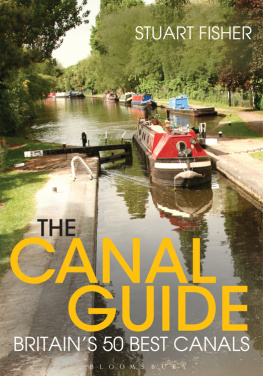

We are fortunate to have, in this country, a canal network like no other in the world. It was the first commercial canal system, leading the way for the Industrial Revolution, but has remained largely as it was originally built. The canals are mostly small and intimate. Restoration in recent years, supported by lottery and other funding, has outstripped the pace of construction even during the canal mania years.

Overseas, where canals have been enlarged to take modern commercial craft, you can look at the distant bank and wonder whether you will be run down by something the size of an office block. In this country the biggest risk is running aground and you can usually wade through the mud to either bank; a canal is a safe environment in which there is limited scope for getting into serious trouble. For the walker and cyclist, canals provide routes that are mostly flat. As far as possible, descriptions are given downhill and with the flow for those who have a choice of direction.

We have canals with scenery that changes frequently: open countryside, wildlife, heritage industrial buildings, canalside public houses, modern city centres, wild moorland and coastal harbours, all mixed up. Anywhere on the system fantastic engineering structures can be found.

For those with suitable boats there are 65,000km of navigable river in England and Wales alone; scope for a whole library of books, but in this one I have concentrated on Britains 50 best canals. Not all of them are linked to the rest of the system and not all are physically passable for many boats or have useable towpaths. You may need a spirit of adventure, like the earlier recreational boaters.

Who uses the canals? If you look at canal magazines you will see smiling couples or families busy in the summer sunshine. In practice, you may find the picture rather different. Often the canals are deserted, except for wildlife that finds them an ideal environment, without needing all humans and boats to be banned.

The intention is that this book should be engaging to all who travel the canals. I do not usually give navigation instructions, depths and headrooms, portage routes or what to do when the towpath runs out. If the present state of a canal is such that it is limited to one kind of user, usually someone able to undertake portages, I may refer to that category of user, otherwise I talk more generally. I draw attention to features near the canal, especially in heritage cities such as Bath and Chester, because most canal travellers will not want to pass through these without stopping.

Much in the future will depend on volunteers. As walkers and cyclists are often the major users of canal routes the Canal & River Trust (CRT) will need to have a more positive approach towards them, including signposting routes at tunnels and other places where towpaths do not follow the canal, removing barriers from towpaths and ensuring routes connect rather than making just token sections available.

Along the canals there are some consistent trends. Heavy industry is evaporating. Public houses across the country are closing at a rapid rate, canalside pubs included, although a number have been converted to restaurants. Virtually anything which can be converted to housing, including warehouses and other former industrial premises, is now packed with residential occupants.

The canals may be ever-changing but theres a sign that more and more people are rediscovering them and taking them to their hearts in recent years canal holiday bookings have shot up.

| Birmingham Canal Navigations: Old Main Loop Line |

Distance

10km from Tipton Factory Junction to Smethwick Junction

Highlights

Telfords listed Steward Aqueduct, where motorway passes over railway, which passes over canal, which passes over canal

Oldest working locks in Britain, at Spon Lane

Galton Valley Canal Heritage Area

Telfords Engine Arm Aqueduct

Navigation Authority

Canal & River Trust

Canal Society

Birmingham Canal Navigations Society

www.bcnsociety.co.uk

OS 1:50,000 Map

139 Birmingham & Wolverhampton

Possibly because Birmingham is the only major city not located on a large river, it has had to rely on its man-made waterways, having more canals than Venice. The whole canal network spreads out from Birmingham and it is to the Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) that all the loose ends connect. It is, therefore, intensely complex, completely built-up and industrial. Its commercial influence is declining but remains sufficient to reduce its attraction as a cruising waterway, resulting in lighter traffic.

Of Britains operational canals, only the Fossdyke and the Bridgewater pre-date the Birmingham. The Birmingham Canal Company were authorised to build their line in 1768 and the following year Brindley opened it as far as Wednesbury. The whole 36km course was completed in 1772 and, because of the minerals and industry along its route, it was immediately highly successful.

Many of the loops of the old line have since been cut off or filled in, but the section between Tipton and Smethwick remains, and is a contour canal with more features of interest than are found along the more efficient New Main Line. The old line divides from the new at Tipton Factory Junction, just a stones throw from the top lock on the New Main Line.

Next page