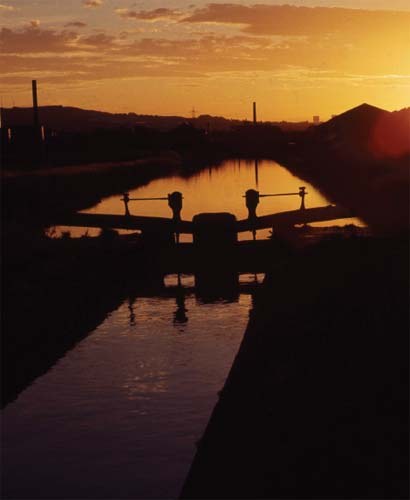

Factories reflected in the water of the Aire and Calder Navigation at Knottingley. The town became prosperous for its glassworks, chemical industry and boatbuilding. Kellingley colliery near Knottingley is the last working deep coal mine in Yorkshire.

Paddington waterside.

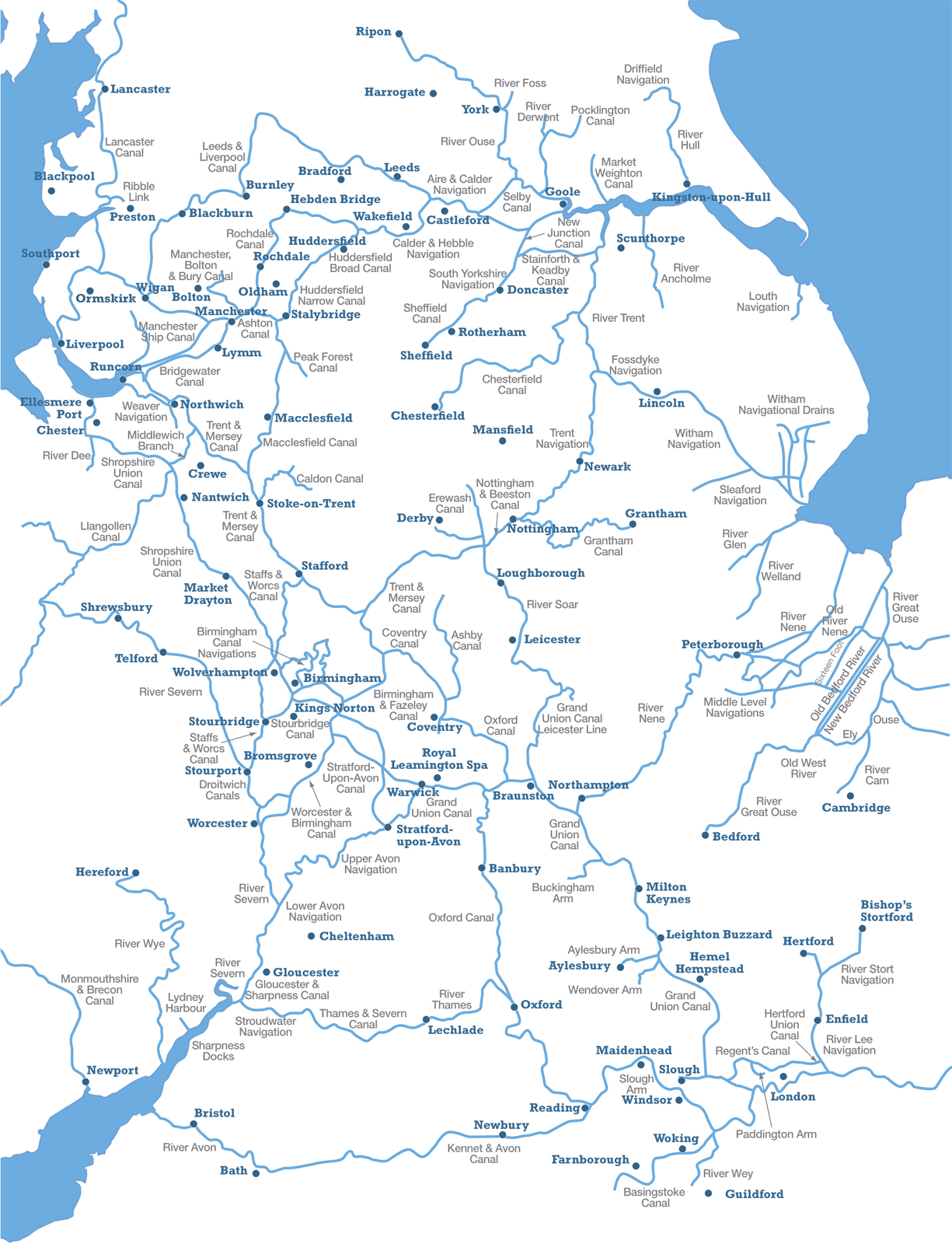

The Industrial Revolution began in the mid-18th century and changed England from an agrarian to an industrial economy. While goods were transported by the countrys major rivers, there remained large areas where they could only be moved by packhorses or horse-drawn wagons. Unfortunately, roads were difficult to build, expensive to maintain and usually impassable in winter.

Many of the new industries were in areas unconnected by navigable rivers. In the north the cotton industry in Lancashire and the woollen industry in Yorkshire were separated by the Pennine Hills. In Staffordshire the potteries established by Josiah Wedgwood were having difficulty bringing in coal and other necessary raw materials. Moving delicate and fragile produce was uneconomical because of breakages caused by the appalling road surfaces. Englands largest industrial region developed around Birmingham because of the discovery of iron and coal deposits in that area. There are no navigable rivers around Birmingham, so manufactured goods had to be transported by road to the River Severn, where they were loaded into barges. In the south, London was separated from the Midlands by high ground, and the upper reach of the River Thames was cut off from the River Severn by the Cotswold Hills.

The solution to this problem was the building of canals to connect the new industry to rivers and ports. Some canals had been built earlier but these were either drainage channels or cuts to straighten out existing river navigations. The Canal Age really began at Worsley near Manchester in 1760. The third Duke of Bridgewater, frustrated by the exorbitant toll charges on the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, decided to bypass them and build his own navigation. The Dukes agent John Gilbert engaged the pioneering engineer James Brindley to build the canal, and the result was the Bridgewater Canal, which carried coal directly from the Dukes mines at Worsley to Manchester, halving the previous cost of coal. Inspired by the success of the Bridgewater Canal, most of the canals that followed were promoted by industrialists like Josiah Wedgwood and engineered by Brindley. Brindley went on to complete his vision of a Grand Cross of canals, which connected industrial areas to the major rivers and through them to the ports. The writer Thomas Carlyle wrote that Brindley chained seas together; the Mersey and the Thames, the Humber and the Severn, have shaken hands. The hub of these early navigations was Birmingham and its industrial heartland known as the Black Country. Once the canal arrived, industry in the shape of factories, foundries and mills was built on its banks. Workers needed somewhere to live, so former villages expanded into towns. The urban waterway was born.

Most businesses had their own loading area where boats could pull in alongside the wharf, and in some cases bigger companies built their own private arm away from the main line of the canal. These arms can still be seen in urban areas, marked by the raised towpath over the entrance to the dock. In many cases the docks have now been filled in. Horse power was the driving force in those days and the towpath was the workplace of the boat horse. Despite being in the centre of towns and cities urban canals were often private, enclosed places. Some waterside inns provided stabling for the horses while the boatman enjoyed a few hours of recreation. For a working boatman this was just an occasional luxury as he had collection and delivery times to meet.

The early canals were so successful that in the 1790s more and more were being constructed throughout the country; this period was known as Canal Mania. New canals continued to be built for another 40 years until the advent of railways diverted business and speculators money into a newer and faster form of transport. Many canals were bought by the new railway companies, who allowed them to deteriorate through lack of maintenance. Business on the canals slowly declined through the 19th century and continued into the 20th century when many canals fell into disuse. In some urban areas local authorities urged the infilling of derelict canals, which had become a dumping place for rubbish. Access to the towpaths was made difficult by bricking up entrances. In many cases this did not prevent children finding a way onto the canal but it did prevent adults coming to the aid of the children when they fell into the water.

Some canals still survived because carrying bulk cargoes by water is a cheap form of transport when time is not important. It was the advent of motorways and the severe winter of 196263 (when the canals froze and were unusable) that finally put an end to canal carrying as a commercial venture. The future of canals lay in the leisure industry.

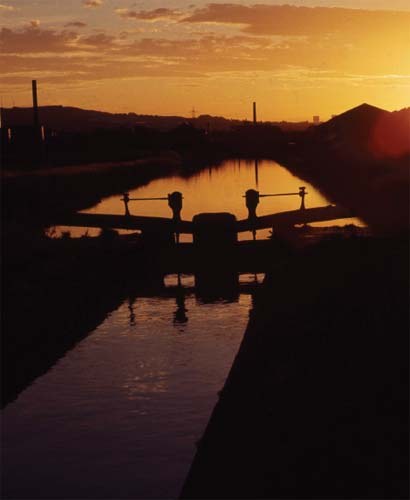

Spon Lane Locks, Birmingham Canal.

In 1939 the author LTC Rolt made an epic voyage around the decaying waterways in his boat Cressy and wrote the bestselling book Narrow Boat, demonstrating and encouraging public interest in the canals. After the war Tom Rolt, together with colleagues Robert Aickman and Charles Hadfield, met in London and as a result of that meeting formed the Inland Waterways Association. Relentless campaigning to change policies and attitudes saved many of todays popular cruising waterways from extinction. Other waterways which had fallen into dereliction were restored back to full navigation by voluntary labour with support from local councils and official bodies such as British Waterways.

Straight Mile, Leicester.

Now there are around 60,000 boats registered on the waterways and thousands of people take their holidays on a hire boat. Towpaths in urban areas were opened up for public use and in some cases have become part of long distance footpaths. Many fine old buildings (such as the warehouses in Gloucester Docks) have found new uses as offices, recreational centres and museums. Disused factory sites have been cleared and the space used for commercial units or waterside housing. The old urban landscape, previously dominated by smoky factory chimneys, has completely changed. Estate agents are extolling the virtue of living next to water and some councils have landscaped run-down waterside areas and turned them into parks. Information boards about the waterway and its history are now a common sight by urban canals. What they cant impart are the mysterious smells wafting from food factories, the hiss of steam outlets and the hum and clatter of machinery.

The aim of this book is to show pictorially the English urban waterway in its contemporary setting, with occasional references to its past. All the locations in this book are on the connected 2,000-mile waterway system in England. Thanks to the restoration movement, it is now possible to travel by boat from Bristol to York or from London to Liverpool. Urban waterways have a large part to play in these journeys.