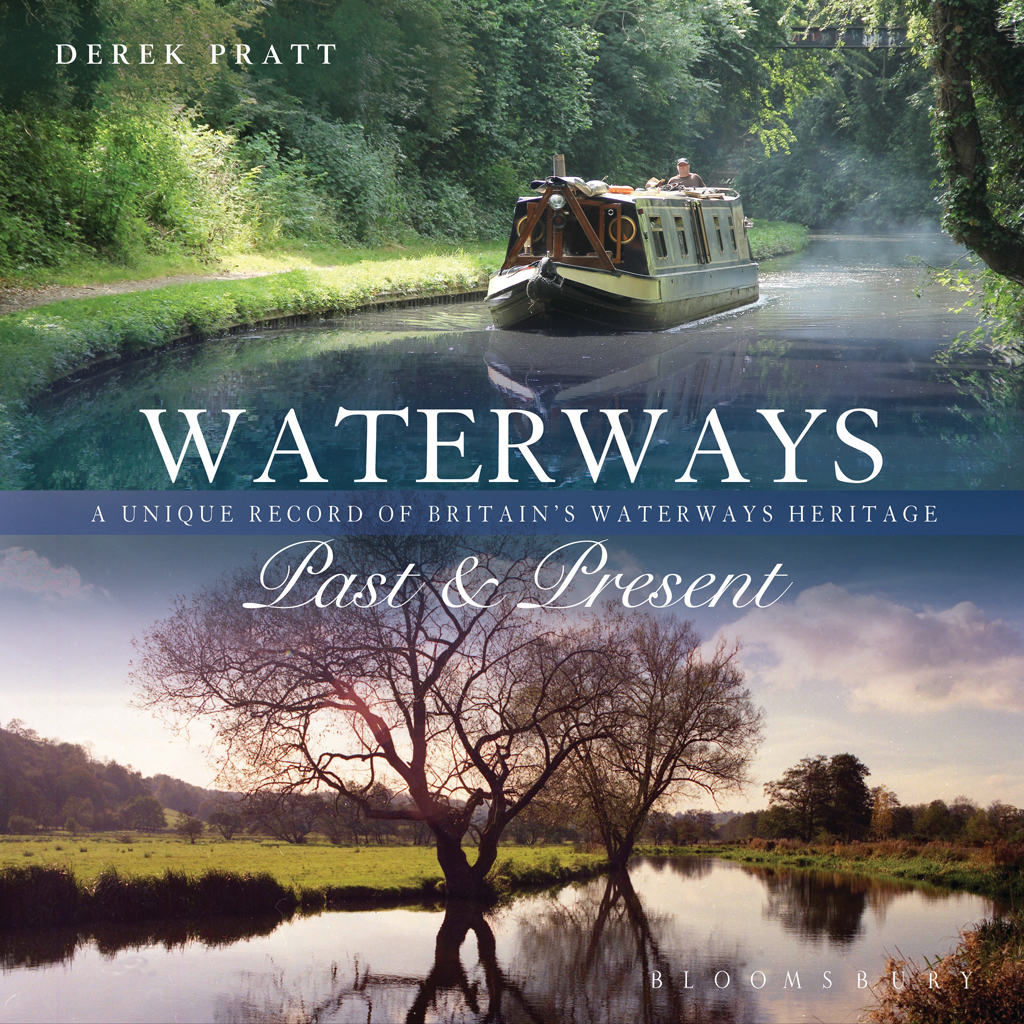

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Adlard Coles Nautical

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

ADLARD COLES, ADLARD COLES NAUTICAL

and the Buoy logo are trademarks of

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in 2006

Reprinted 2007 and 2008

Second edition 2015

Derek Pratt, 2006, 2015

Derek Pratt has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: 978-1-4729-1201-5

ePDF: 978-1-4729-1266-4

ePub: 978-1-4729-1265-7

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

Introduction: Times of Change

I have never seen anything ugly in my life, for let the form of an object be what it will, light, shade and perspective will make it beautiful.

JOHN CONSTABLE (17761837)

The second half of the 18th century was a time of change throughout the world. In France and America this manifested itself in bloody revolutions, but in Britain a more peaceful change took place. It became known as the Industrial Revolution, and it was the canals that made it all possible. Led by engineers like James Brindley and financed by businessmen like Josiah Wedgwood, they connected the main rivers and ports with artificial waterways.

A second wave of canal building came during the first quarter of the 19th century. Thomas Telford and his contemporaries had learned the lessons of James Brindley and the pioneer canal builders which were to keep the new canals in a straight line and avoid the earlier meandering, contour hugging waterways. The new canals had deep cuttings and embankments keeping locks bunched together in long flights. Journeys on the older canals were too slow when economic pressure demanded a fast delivery of cargoes.

The Stockton and Darlington Railway opened in 1825 heralding a warning to all inland waterborne transport. Railways were built throughout the country with the same enthusiasm and speculation that had greeted the height of canal building fifty years earlier. The railways didnt have summertime water problems and could still operate in freezing conditions. They could also handle bulk cargoes and were quicker.

During this period the boating families were forced to leave their canalside cottages and move into the cramped boat cabins. The new aggressive competitor meant that costs had to be cut and the boatman could no longer afford to live ashore. An indigenous floating population developed with their own traditions, that lasted over a hundred years. That period of time saw the slow decline of commercial carrying on most of the canals, with some of them gradually becoming uneconomic and forced to close.

This situation was often accelerated by the purchase of canals by railway companies who then allowed their watery competitors to decline through lack of maintenance.

The boating families who toiled up and down the English canals in 1850 would have still recognised most of the familiar places if a time machine could have propelled them into the mid-20th century. The fabric of the waterways remained constant with its mills and warehouses, wharves and factories. The bridges, locks, tunnels and aqueducts were still there although motorboats had replaced traditional horse-power.

By 1960, the first motorways had made their appearance and the railways began to suffer the kind of competition they had inflicted on the canals over a hundred years earlier. The severe winter of 19621963 finally brought an end to regular commercial carrying on the narrow canals.

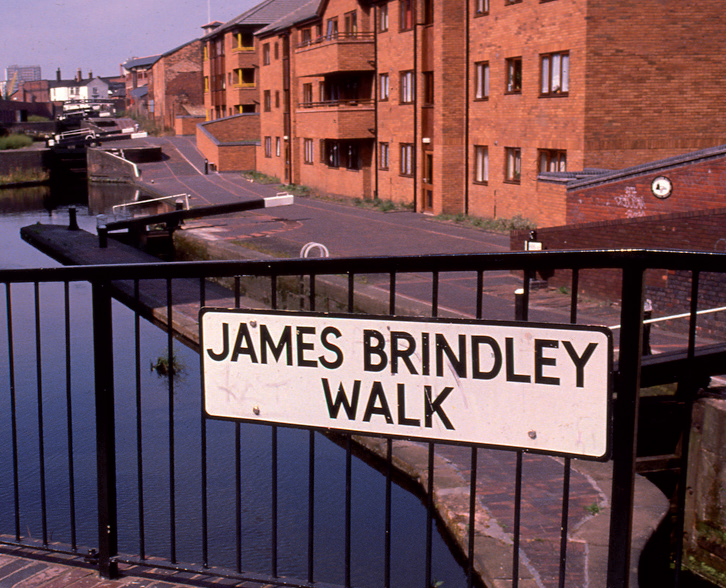

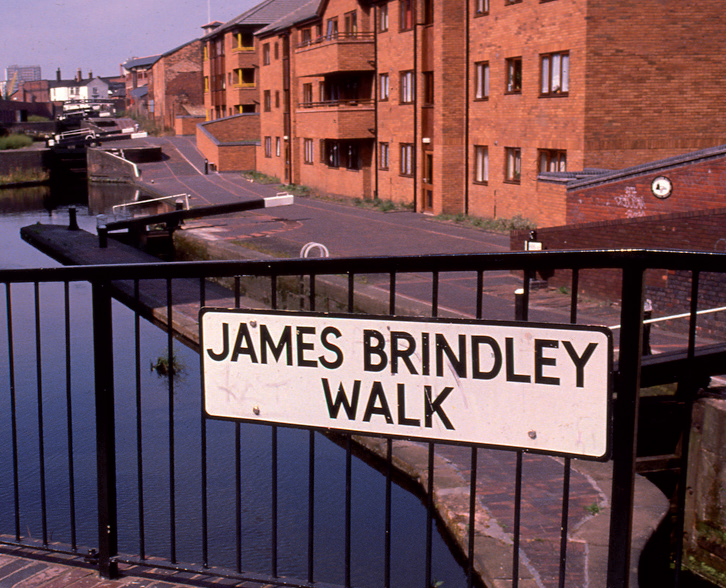

Project the boatman from 1850 to the start of the 21st century and he would be bewildered to see the changes in his former working environment. The Victorian warehouses and mills have either been demolished or transformed into offices and apartments. New bridges cross the waterways with the cacophony of modern motor transport, and pleasure boats fill the locks and line the banks. Place him at Old Turn Junction or Gas Street Basin in the centre of Birmingham, and he would struggle to find anything recognisable. The same would apply at Paddington Basin or the former Brentford Dock in London. Regents Canal Dock is now Limehouse Basin, filled with pleasure boats and housing for City workers. Today there are Brindley Houses, James Brindley pubs, Telford Way, Narrowboat Way and Boathorse Hill. All these names refer to new roads, housing developments and commercial science parks, recalling the men who built the canals and worked upon them all those years ago.

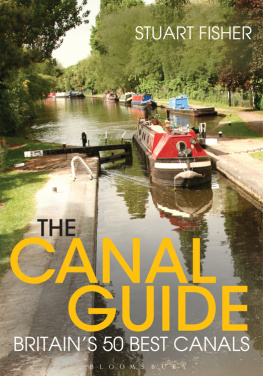

Caen Hill Locks, Devizes, Kennet and Avon Canal.

PART ONE

The Age of Brindley

Was James Brindley the greatest canal engineer? Waterway historians and writers point to the achievements of such worthies as William Jessop, John Rennie and Thomas Telford. All were great men in their time, but Brindley was the pioneer canal engineer whose example was set for all his successors to learn from. When Brindley built Harecastle Tunnel it was the first time anyone had attempted such a monumental feat of engineering. He encountered numerous geological obstacles that took years to overcome, but in the end he succeeded. When Telford built his adjacent tunnel fifty years later, most of the problems had been solved and he also had the advantage of more modern surveying methods and civil engineering techniques.

Statue of James Brindley at Etruria, Stoke-on-Trent.

Brindley is remembered by this street name in Birmingham.