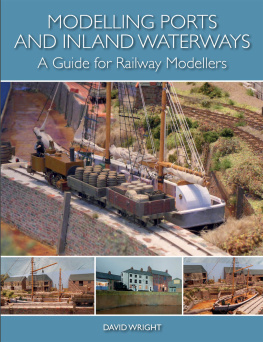

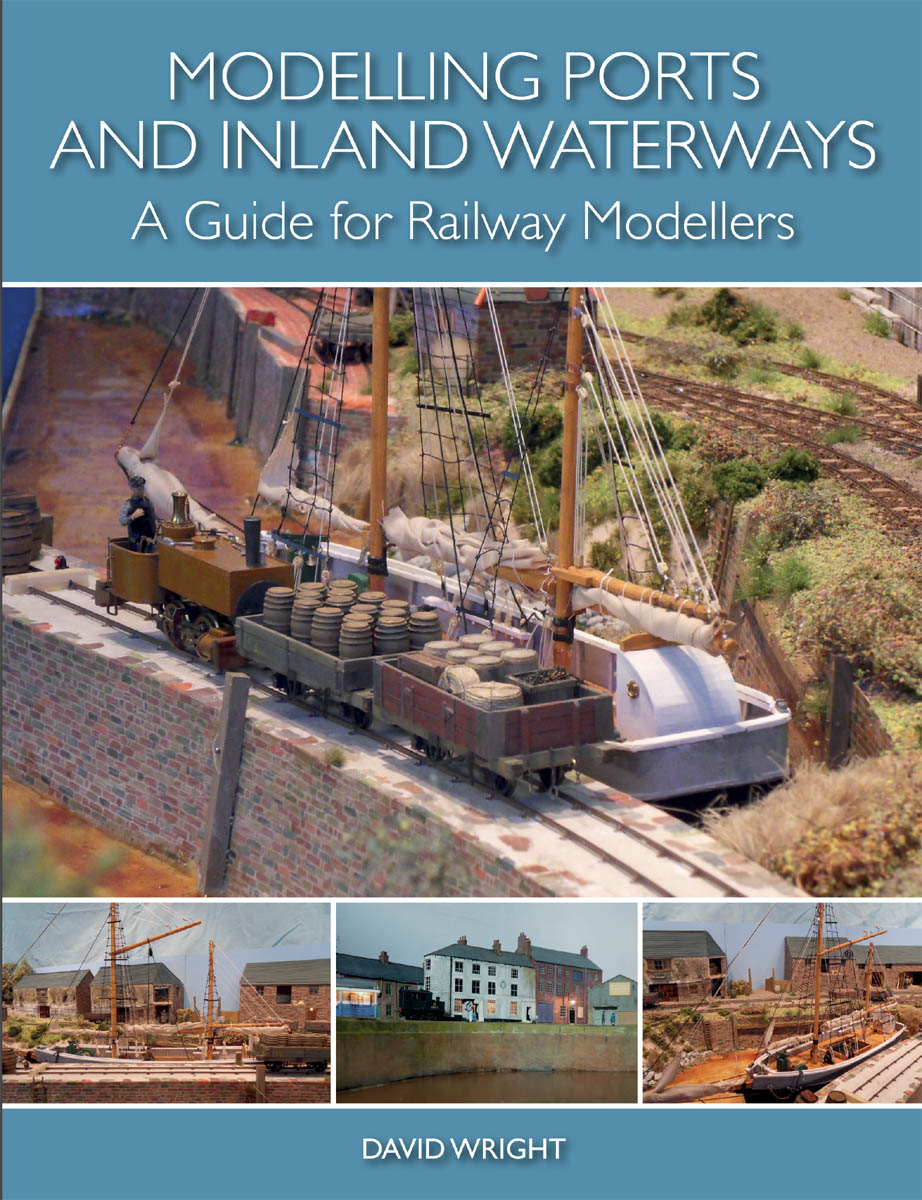

MODELLING PORTS AND INLAND WATERWAYS

A Guide for Railway Modellers

MODELLING PORTS AND INLAND WATERWAYS

A Guide for Railway Modellers

DAVID WRIGHT

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

David Wright 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 168 0

Disclaimer

The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it.

Dedication and Acknowledgements

I would like to dedicate this, my fourth book, to my late father Jim. It was Dad who took me on many trips to the coast, which left many memories in the mind of a young boy. These happy memories have inspired much of this book.

Also I would like to pass on my special thanks to the following: Chris Peacock, Phil Waterfield, Alan Kirkman, Malcolm Wright, Mike Edge, Martin Nield, Dave Bailey (Skytrex 2013), Phil Morris (PLM Cast-A-Ways) and The Tramway Museum Society for their contributions towards this book.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Following the production of my last book on modelling branch lines, it was suggested that another, similar work would be a good idea. This time, however, the subject would be modelling the railways serving the ports and inland waterway wharfs. As a young boy growing up in the 1960s I witnessed the end of steam on the railways and the decline of our major ports. Living in land-locked Derbyshire, my father would take me and my brothers to see the passenger liners and merchant ships docking at Liverpool and other major ports, and I still have fond memories of these trips, including the many dock railways in operation as well as the ships. These early recollections certainly inspired me to put this book together, and through the following chapters I have presented a comprehensive collection of reference material, and I hope have also given a good selection of layout ideas.

It was always my intention to present a mainly visual book for this subject, using both illustrations and photographs as a guide, so making the book a valuable addition to any keen modellers collection. I also sincerely hope that the contents of this unique publication will inspire you to build a model railway with connections to an inland or coastal port.

A BRIEF HISTORY

If we go back through history we will find that the earliest methods of transportation were by water. The sea and the rivers were the obvious choice, and our ancestors built primitive boats for moving both people and goods around. The rivers were made more navigable, and sheltered ports and harbours started to be built on the coast and along tidal river estuaries. However, the main choice of transportation inland to carry goods was the packhorse, and a number of drovers roads criss-crossed the country. Later, turnpike roads were built, with horses and carts carrying the bulk of the goods, and stagecoaches transporting passengers.

During the mid-eighteenth century there were further innovations to transportation in Britain. In this period the country experienced the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, and with it the creation of the canal system. Moving goods on specially built waterways proved very successful, as boats had a much greater capacity to carry goods and could offer a safer passage for any delicate cargo such as pottery.

THE EARLY RAILWAYS

The first primitive tram roads started to appear at the same time, and our railways had their origins in these. Some early examples used slabs of stone with a groove cut into them, in which the wagon wheels would run. Most of these tramways would link quarries or mines to a transhipment point alongside a canal, while others connected with a coastal or river port. A good example of one of these was the Haytor Tramway, which transported quarried granite down from Dartmoor to the Stover Canal; the stone would be loaded on to boats to continue the journey by water. The canal had been cut to create a link with the River Teign estuary.

The Haytor Tramway was built to transport granite down from the quarries on Dartmoor to the Stover Canal. Barges would then take the cargo along the short length of canal to the Teign estuary and Teignmouth, where it was trans-shipped on to larger ships.

The Ticknall Tramway carried lime from the lime kilns near Ticknall to be trans-shipped on to narrowboats on the Ashby Canal. The picture shows the old tramway bridge at Ticknall being investigated by members of Burton Railway Society.

This was still a long time before the invention of the steam locomotive, with teams of horses providing the motive power to pull trains of loaded and unloaded wagons.

During the Industrial Revolution the innovative procedure of smelting iron meant that this material could be used to make rails; the rail sections could then be easily mounted on to a stone block sleeper. Thus the first proper railways were created, and it wasnt long before these were used to transport materials. Experiments were being made to develop the steam locomotive, with Richard Trevithick leading the way, although horses were still used in those early days.

One of the stone block sleepers used on the tramway.

Nevertheless the iron horse soon started to replace its live counterpart. The steam locomotive was first introduced on the Stockton & Darlington Railway in the north-east of England, carrying coal from the mines around Darlington down to the port of Stockton-on-Tees. Stephensons famous locomotion became the motive power on this first steam-hauled railway.

This painting by the author depicts coal being loaded by hand from railway wagons on to the narrowboats at Hartshay Wharf. The coal was extracted from the colliery nearby and shipped along the Cromford Canal by boat. Most of the coal was destined for the engine houses along the High Peak Railway.

Other minerals, mined and quarried, were transported by the tramways and railways from their source to be trans-shipped later on to boats. North Wales became Britains centre for slate production, with large quarries extracting this roofing material in vast amounts. All this was transported by rail down to the ports on the coast. Unlike the Stockton & Darlington where the gauge was wide, these railways were built to a narrow gauge.