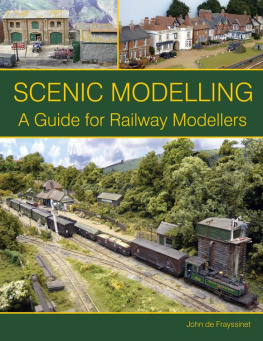

MODELLING BRANCH LINES

A Guide for Railway Modellers

DAVID WRIGHT

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

David Wright 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 020 1

Disclaimer

Power tools, glues and other tools and equipment used to create model scenery are potentially dangerous and it is vitally important that they are used in strict accordance with the manufacturers instructions. The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it.

Photographs by the author unless credited otherwise.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

When I was first approached by the publishers about producing a book on modelling railway branch lines, the idea certainly attracted my attention, although the prospect of covering such diverse subject matter did appear rather daunting. My intention from the start was to produce a book that would present modellers with as much information as possible and provide them with the inspiration to create a realistic representation of a British branch line. I also wanted to produce a book that would offer railway modellers something a little different from all the other publications that have been written on modelling our branch lines. In the first chapter I describe the background history of branch lines and consider their role in the future. I will then look at examples of branch lines from all parts of the mainland of Britain, as well as one of the islands, and proceed to consider how branch line modelling can be incorporated into smaller spaces around the house, garage or even the garden shed. The book is illustrated with photographs, track diagrams, maps, architectural drawings and three-dimensional interpretations of branch line layouts. This is most evident in the chapter that deals with a special branch line layout project. In a separate chapter I examine colour, landscaping and creating the settings in which to place the branch line models. I hope that both the text and the illustrations will give you, the modeller, a good reference point for starting a model of a branch line.

THE BIRTH AND EARLY YEARS OF THE BRANCH LINE

Branch lines usually summon up the image of a sleepy single-tracked railway winding its way through our green and pleasant rural countryside to reach a terminus in another sleepy market town or village. This idea would be accurate in most cases, although a good number were built to serve industry and did not have the rural ambience that generally comes to mind when the term branch line is mentioned.

The Haytor Tramway was built to transport granite from the quarries on Dartmoor down to the Stover Canal at Teigngrace for trans-shipment on to barges. The tramway used lengths of granite to form the flange way on which simple loaded and unloaded wagons were pulled along by horse.

The Ticknall Tramway in South Derbyshire was built to transport limestone from quarries to the lime kilns. The burnt lime was transported in wagons pulled by horses along primitive iron rails to be loaded on to barges at the nearby Ashby Canal.

Stone sleeper used on the Ticknall Tramway. A spike would be driven through the drilled hole, anchoring the rail down onto the sleeper. This type of track was used on many of the early tramways and railways.

A good number of our branch lines did not terminate in a country station either. These lines were smaller link routes, linking one major main route to another. Most of these were also laid to double track. Another variation was the loop line, again usually laid to double track. These routes would branch off a main line to serve a community before rejoining the same major route.

The history of our branch lines goes back to the very first railways, originating with the horse-drawn tram and gangways. These primitive forms were laid down to provide transportation of stone, coal or slate, together with other materials and commodities, to a transhipment point, usually a river or a canal. Some would be laid to move them from one stage of processing to another. The early tramways consisted of rails made of materials such as stones forming a flange way. The first metal rails would make an appearance following the industrialized smelting of iron. The individual sections of fish-bellied rail were dovetailed together and sat on individual stone block sleepers. Another feature of some of these early railways was the use of inclined planes. This was a means of moving the goods over the steep contours of the land using cables to pull the wagons up and down the incline. Early forms worked by gravity with a loaded set of wagons running down, pulling the empty wagons up. The introduction of a stationary engine would improve the operation of this system. The Swannington Railway in Leicestershire was the first to use this method. One famous railway to use inclined planes, not so far away in Derbyshire, was the Cromford & High Peak Railway. Here a number of inclines were included to traverse right across the hills of the Peak District linking the Cromford Canal in the Derwent Valley with the Peak Forest Canal in the Goyt Valley. I will cover the Cromford & High Peak Railway in more detail later in the book, looking at how this unusual railway would make a good model branch line project.

A sample of the type of cast (fish-belly) rail used on the early railways, here stamped with the letters C. & H. P.R. Co. (Cromford & High Peak Railway Company).

Using railways to move passengers as well as goods did not happen until 1825 with the opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway. The first major route built to link two cities was the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, opened in 1830. It was not long before the railway boom started in earnest, with the railway barons building lines to link all the major towns and cities, generating large profits from this new transport system. Along with the major arteries, secondary routes were also constructed. It was soon realized that linking dairy and livestock farming areas, as well as industrial quarries and coal mines, could also become very profitable.

Next page