Page List

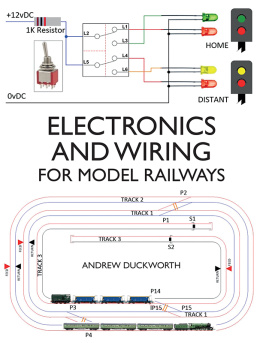

ELECTRONICS

AND WIRING

FOR MODEL RAILWAYS

ELECTRONICS

AND WIRING

FOR MODEL RAILWAYS

ANDREW DUCKWORTH

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2019

www.crowood.com

Andrew Duckworth 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 624 1

INTRODUCTION

My love of model railways started way back in 1962 with my grandmother sending me a Hornby OO kit for my twelfth birthday. I lived in Nyasaland (now Malawi) in those days, and this was the time when post used to take about a month to arrive, and parcels took about two months. There were no mobiles you had to book a telephone call twenty-four hours in advance and it cost a weeks pocket money, or send a telex that was converted in the UK to a telegram, again costing a fortune: so ordering was very difficult. So I resorted to sending requests by post to my grandmother, who would send me parts for my layout three times a year, on my birthday, for the summer holidays, and at Christmas. Over the next four years my first railway grew from a small kit into a large four- by three-metre U-shaped layout. This was, of course, the era when the track was a three-rail system, and all parts were made in metal.

During this period I developed a desire for anything electrical and electronic although the transistor had only just been invented and there were no integrated circuits, it all fascinated me. After my school years I went to a polytechnic in Johannesburg to do a course in electrical/electronic engineering. On completion of the course and with certificate in hand, I applied for jobs in the UK. In my navety I stated that I had a love for model railways, thinking this would help with my job application little did I know. My first job application I received was from a company in Plymouth called ML Engineering. I flew to the UK to start my working career at the age of twenty-one.

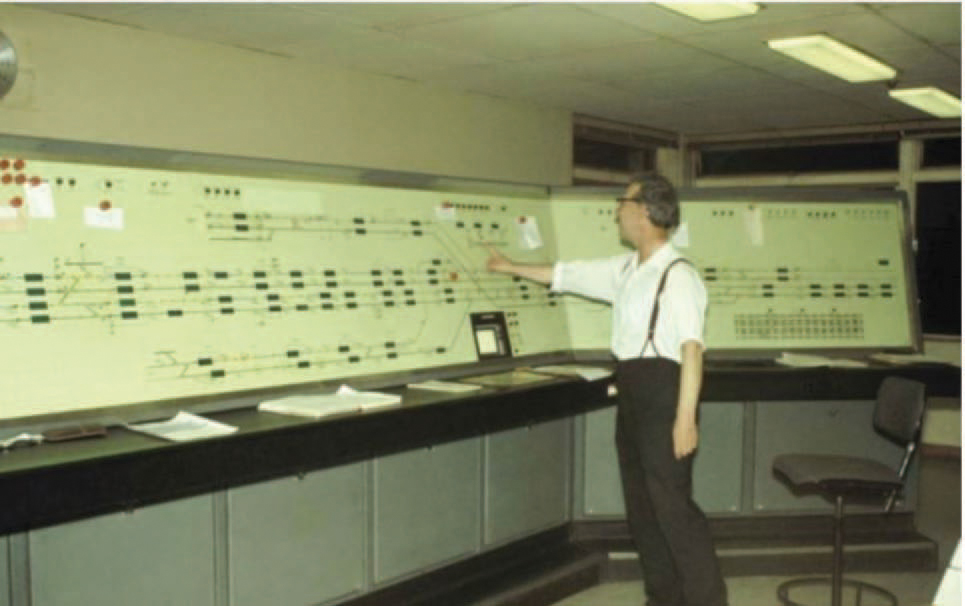

ML Engineering was an American company based in Plymouth, which designed and manufactured electrical systems to electrify British Rail. They designed and manufactured an automatic train detection system (AWS), which looked like a big black rectangular box placed between the rails. This sent a signal to the train and back to the signal box, indicating that a train had just passed over it, as shown in .

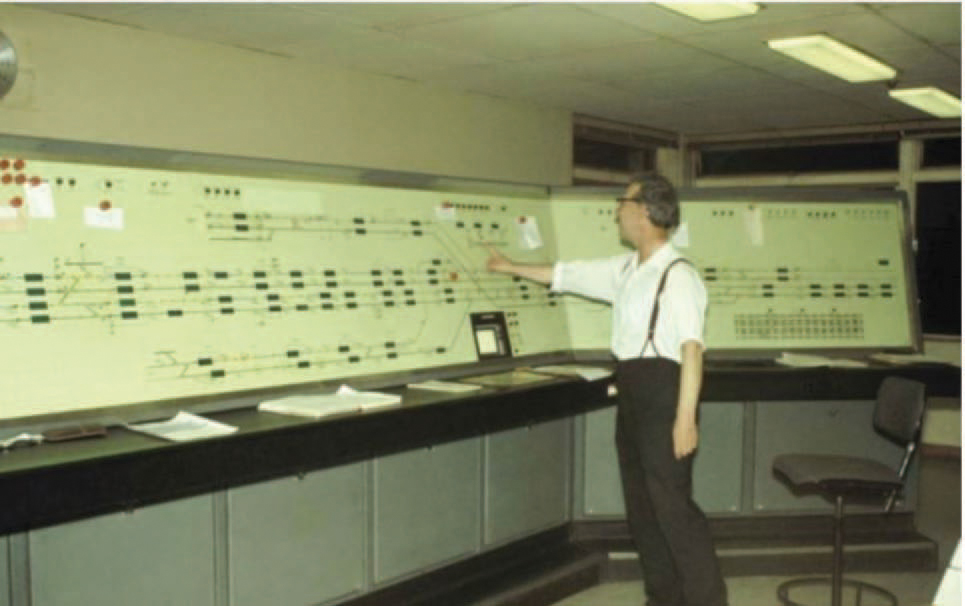

The relay room for most stations was a two-storey building with the relay room under the signal box, and it had racks of relays. Each relay was interlocked with others, so when a points button was pressed on the mimic panel, dozens of relays had to be in the correct position before the current would pass through them to the point motor. This would also put all the required signals in the correct aspect. This was then put on to a mimic display panel, which replaced the levers in the signal box. In my time with the company I worked on Shenfield, Grantham and Crewe signal systems, converting them to electrical mimic displays with push buttons to control the points and the signals, as shown in

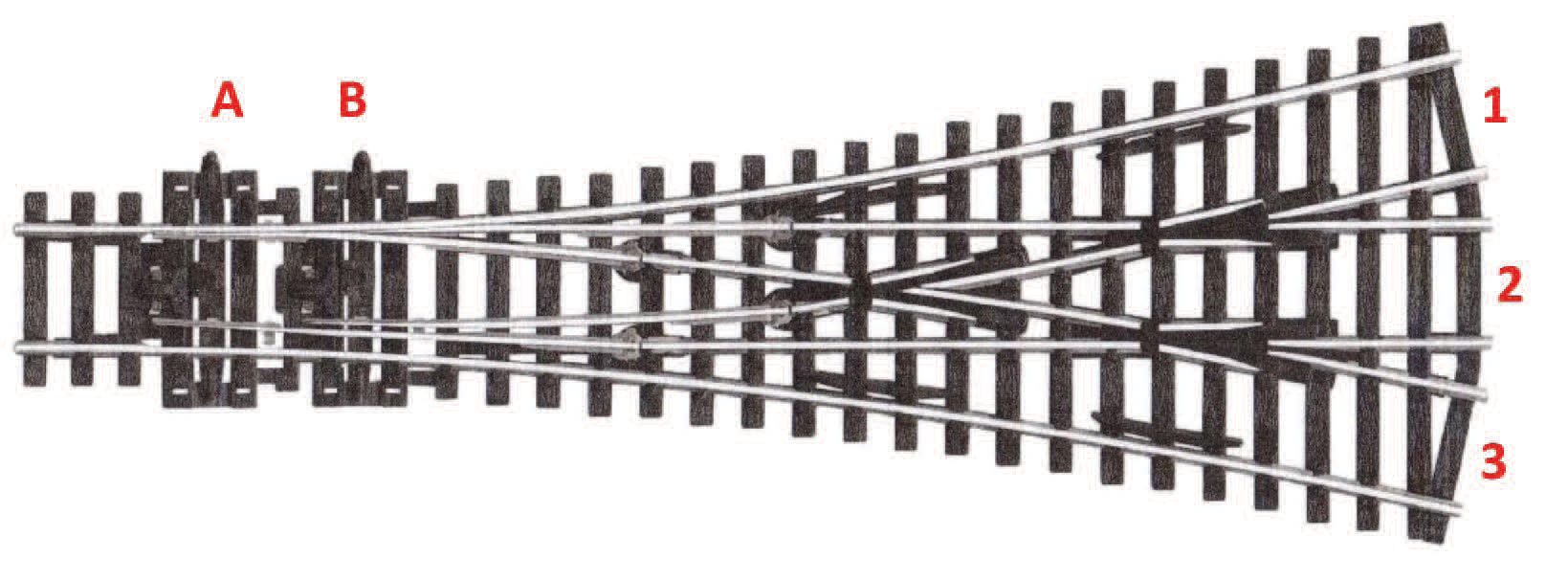

Fig. Int.1 Train sensor.

Fig. Int.2 Relay room. COMPETENCY AUSTRALIA

Fig. Int.3 Mimic display signal box.

I remained with ML Engineering until 1976, when I returned to Nyasaland, now Malawi, to set up my own electronic manufacturing company. I was unable to use my knowledge in the new company, so branched out into other electronic products that would sell in that country, such as AM/FM radios, amplifiers and speed detectors. This was when my original model railway system was brought out of mothballs and rebuilt in my new home. By this time things had changed a great deal in the model railway business. It was now time to update my layout to the two-rail system, again a slow process as everything had to be ordered from the UK but the mail system had improved to seven days, so not so bad.

In 1996 I came back to the UK with model railway system in tow. By this time there were transistors, integrated circuits and microprocessors some of you may remember the Sinclair ZX80 and ZX81 computers introduced in 1981; also in the eighties came Amstrad computers CPC664 and CPC6128. Although very simple by modern standards, they could be easily programmed to do certain functions, a little like the Arduino and Raspberry Pi, to name a few, of today.

Back to the important bit.

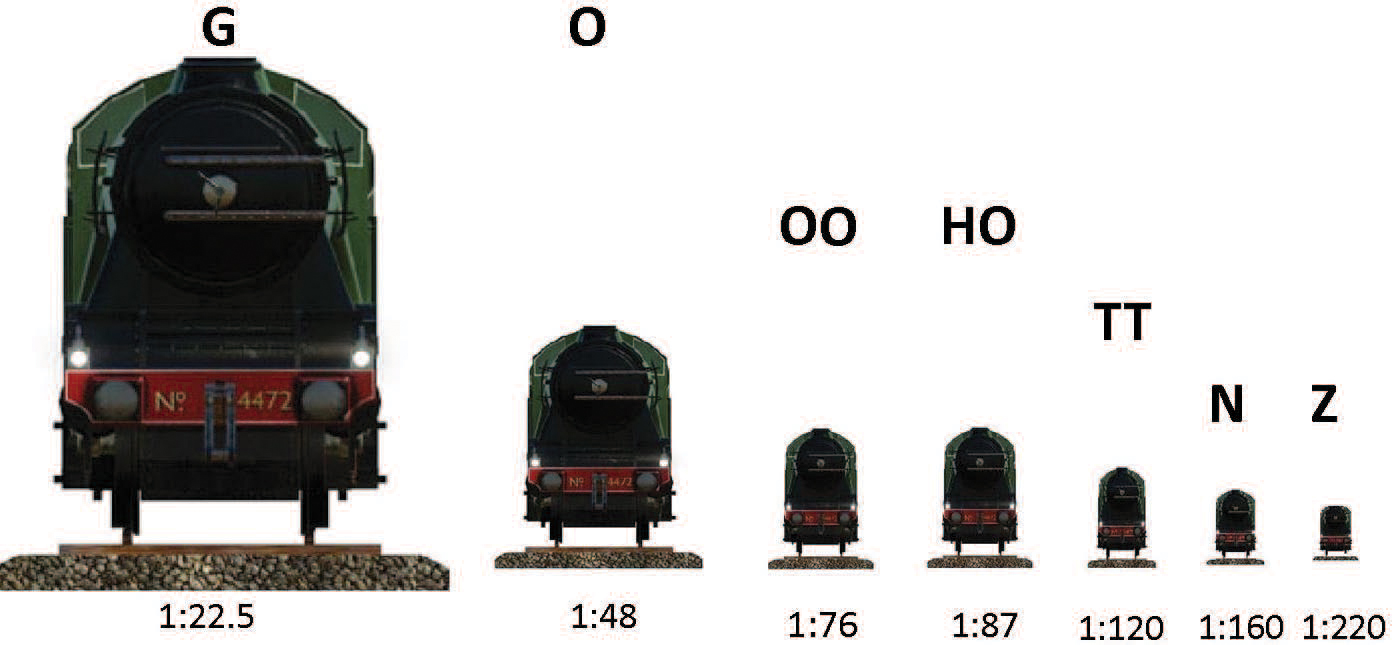

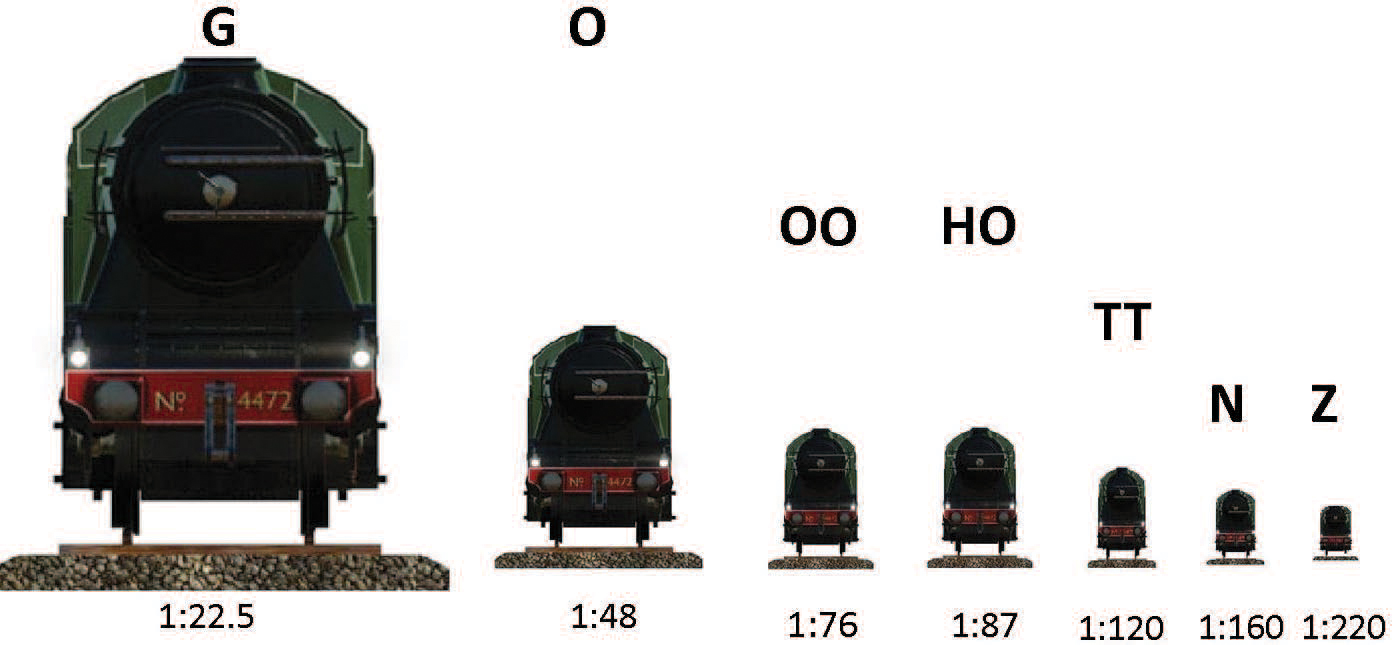

MODEL RAIL GAUGE

There is a difference between gauge and scale. The gauge is the distance between the rails, from the inside of one rail to the inside of the other rail, with trains and rolling stock built for each particular gauge. Scale is the proportion that the size of the model is compared to its real-world equivalent. It is normally expressed as a ratio (1:16 or 1/16) or a size (1in:1ft).

When a model train is scaled down the gauge is not necessarily to scale, but to the nearest standard gauge. This means that you could have two different trains both with the same gauge, but in a slightly different scale. In practice this will be hardly noticeable, but it is worth bearing in mind.

Fig. Int.4 Train size comparison.

Train size comparison chart

| Name | Scale | Description |

|---|

| Z | 1:220 scale | Based on Marklin factory standards |

| N | 2mm = 1ft 1:148 scale 9mm gauge | Twice as small as OO gauge |

| TT | 3mm = 1ft 1:101.6

12mm gauge | This gauge originated in the USA, and was also produced at 2.5mm to 1ft, 1:120 scale.

Enthusiasts using this scale need specialist support through the Three Millimetre Society |

| HO | 3.5mm = 1ft 1:87

16.5mm gauge | This is the major gauge used outside the UK. At 3.5mm to 1ft, the track gauge at 16.5mm is virtually exact to scale for the standard gauge. When using this gauge it must not be confused with OO gauge: HO gauge is almost 15 per cent smaller. One can run HO gauge rolling stock on OO gauge layouts, the track gauges both being 16.5mm, but the difference in scale will immediately become very obvious |