IMAGES

of America

OHIO AND ERIE

CANAL

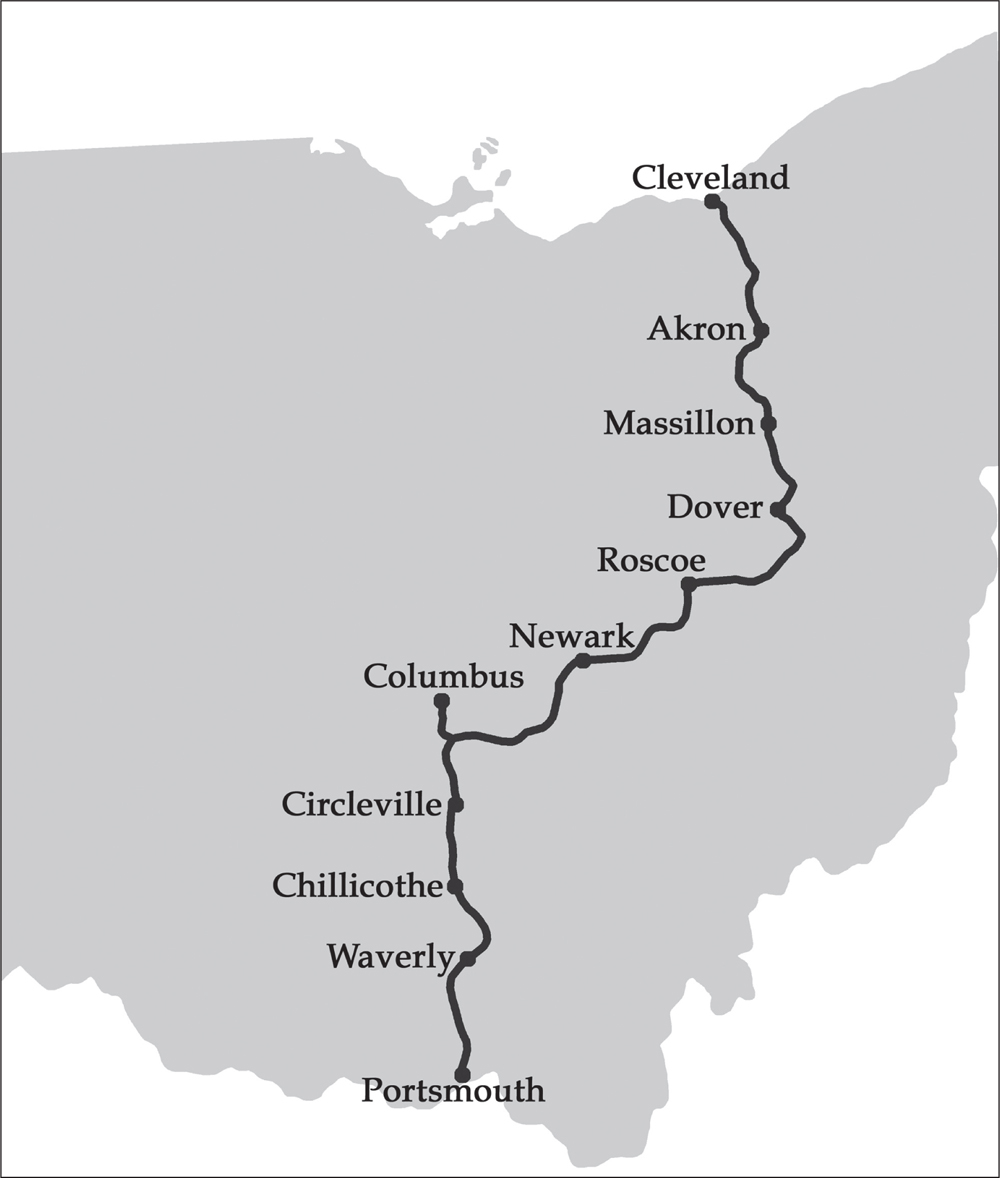

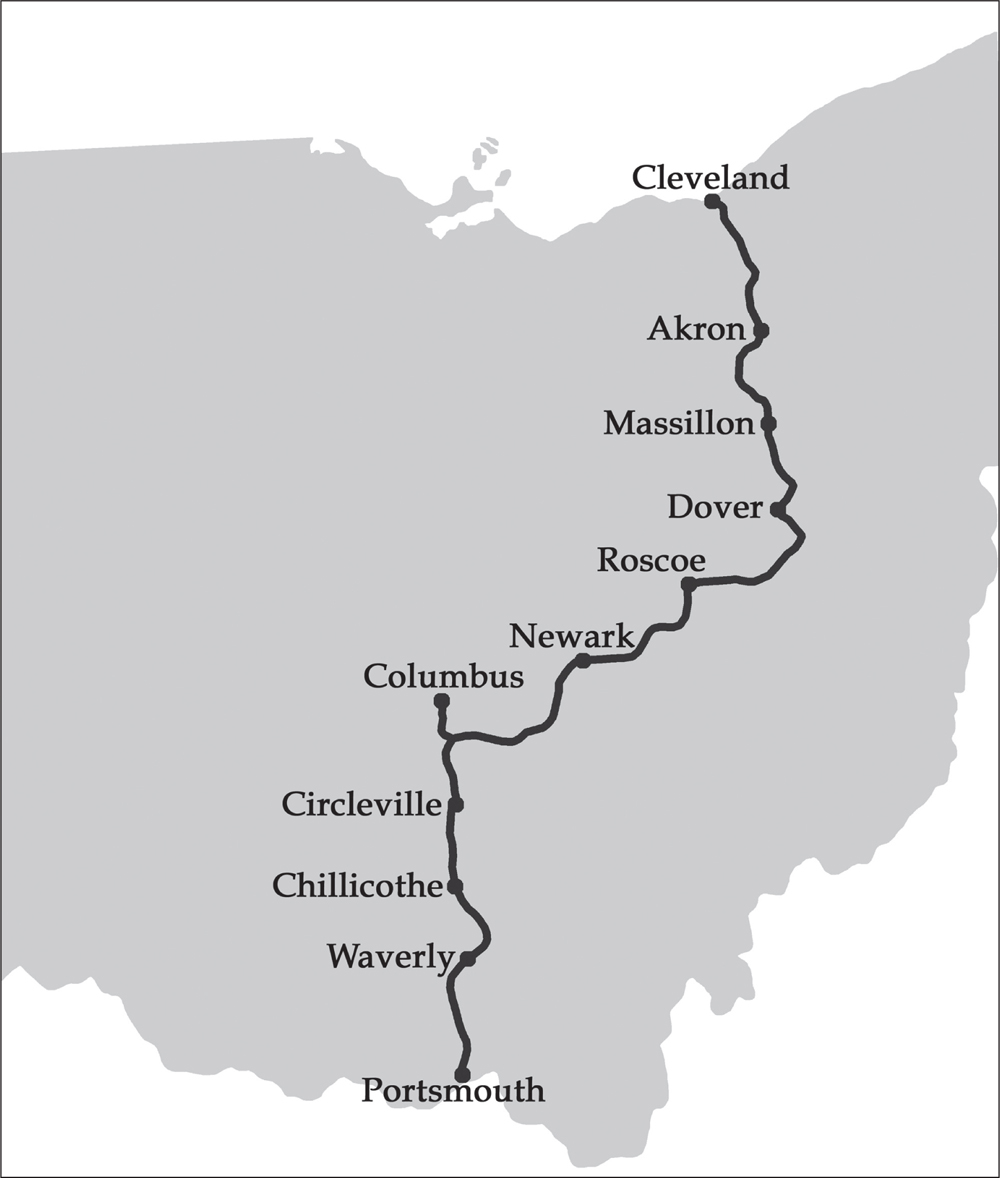

The Ohio and Erie Canal was 309 miles long and connected Lake Erie to the Ohio River. (Authors collection.)

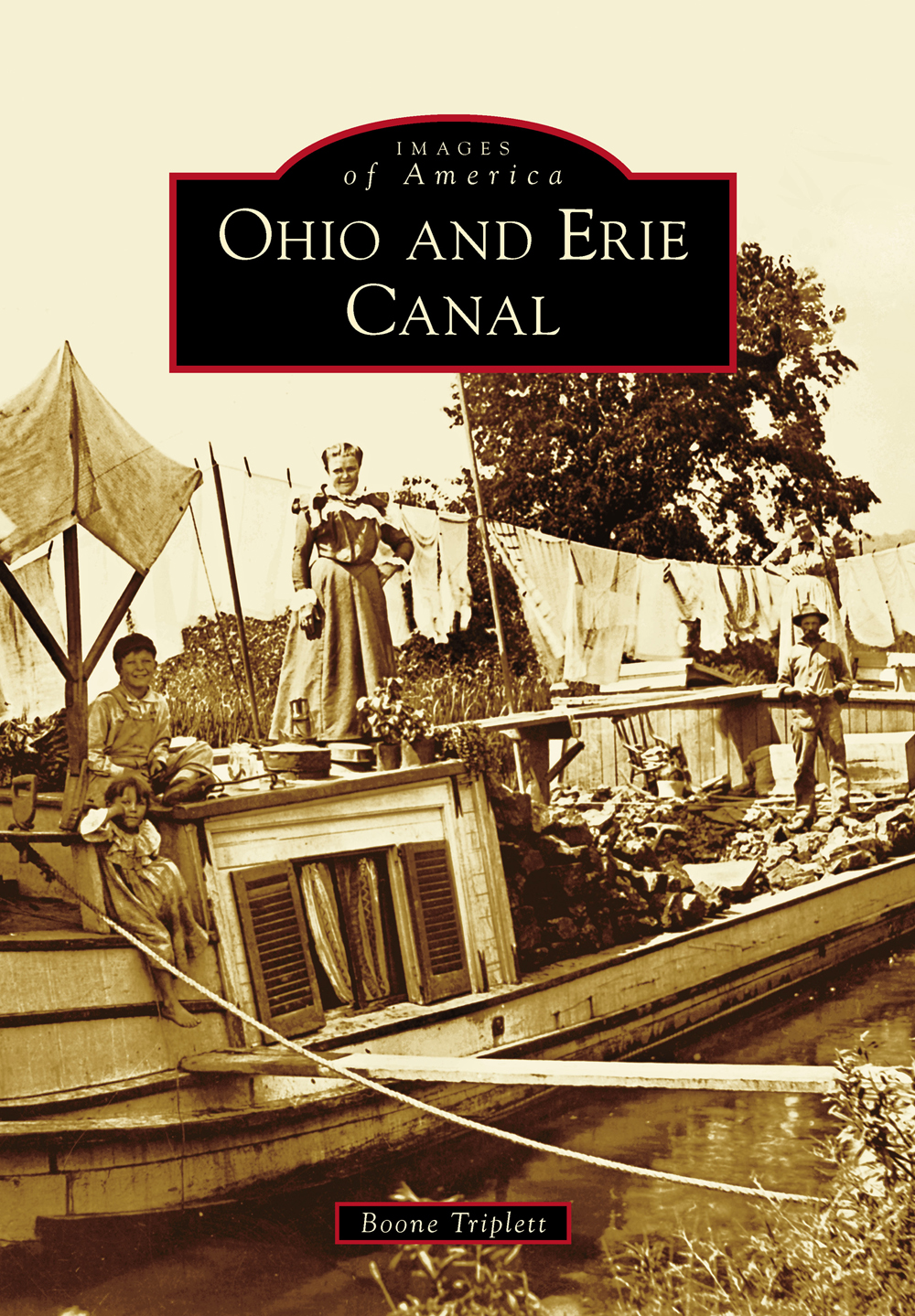

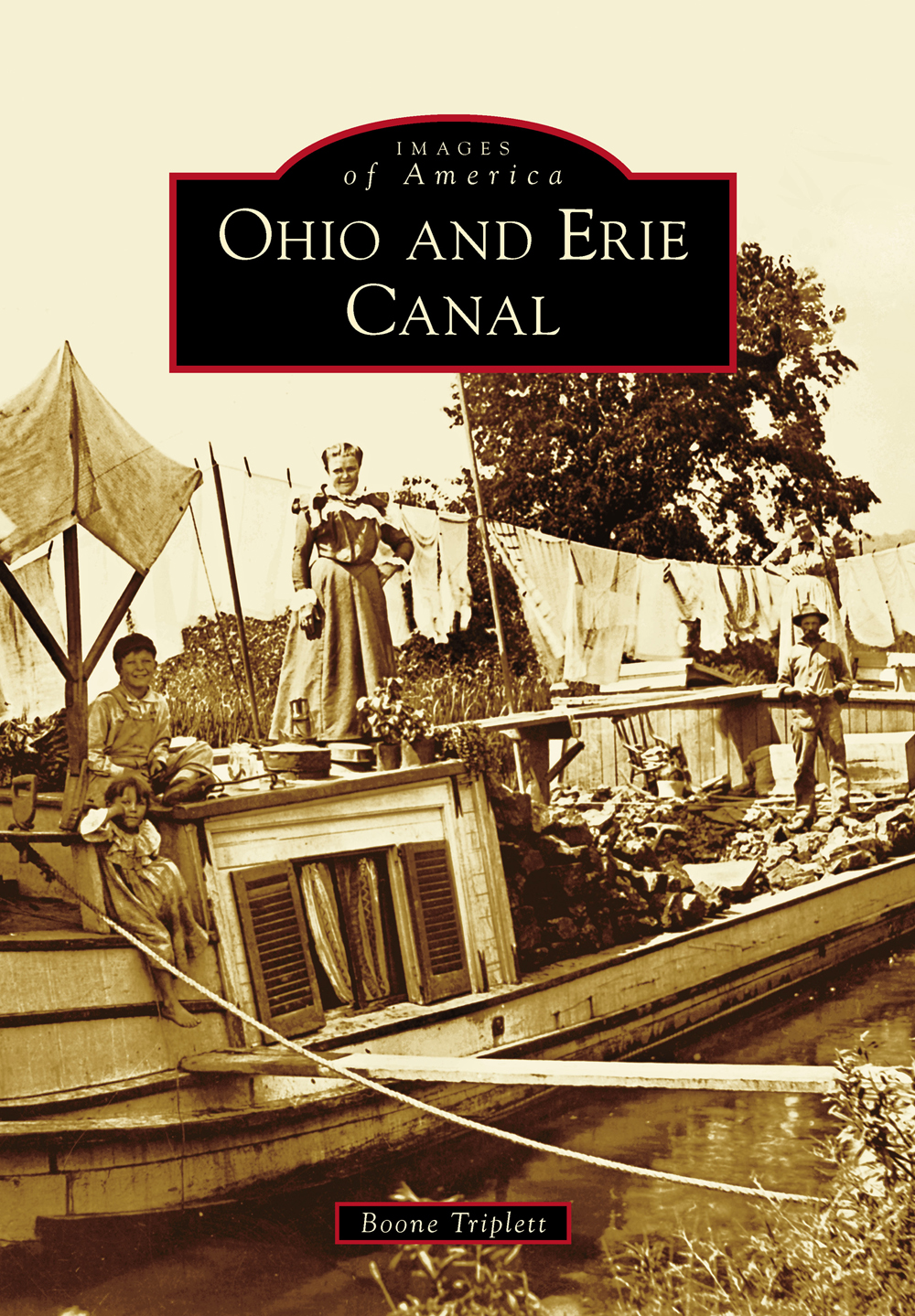

ON THE COVER: Titled Washday on the Canal, this photograph shows a family on an Ohio and Erie Canal boat. (Courtesy of the University of Akron Archival Services, Louis Baus Canal Photograph Collection, OEC_180.)

IMAGES

of America

OHIO AND ERIE

CANAL

Boone Triplett

Copyright 2014 by Boone Triplett

ISBN 978-1-4671-1252-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439646953

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014933627

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Big Jug and Hard Rock

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Obviously, a book such as this would not be possible without the help and cooperation of others. This begins with Canal Society of Ohio (CSO) members Bill Oeters, Dave Neuhardt, Dave Meyer, Terry Woods, and Nancy Gulick. They provided images from their personal collections and/or reviewed the text for historical accuracy. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the author.

Also deserving of acknowledgement is Vic Fleischer of the University of Akron Archival Services. In addition to being caretaker of the CSO collection, Vic provided many images from the Louis Baus Canal Photograph Collection (UA-Baus). Chris Hart, museum curator and living historian at Roscoe Village, generously donated his office and allowed full access to the Roscoe Village Foundation (RVF) photograph collection. Mandy Altimus Pond of the Massillon Museum kindly opened up the William Bennett Collection. Ditto for Mary Plazo and Rowan MacTaggart of the Cascade Locks Park Association (CLPA). Randy Norris and Larry Turner of the Portage Lakes Historical Society (PLHS) allowed me to handle the original glass plate negatives of Edwin Bell Howe. (Larrys enthusiasm for the subject of canals is unmatchedand infectious!) Judy James and Rebecca Larson-Taylor of the Special Collections Department at the Akron-Summit County Public Library (ASCPL) were also helpful.

Ultimate thanks should go to individuals like Baus, Bennett, Howe, and Pearl Nye. If these men did not keep the memory of the Ohio and Erie Canal alive, it may have died away completely during the first half of the 20th century.

INTRODUCTION

The United States had secured its independence from Great Britain, but George Washington was concerned about the new nations future. Immediately after the American Revolution, all trans-Appalachian commerce flowed into British Canada or Spanish Louisiana. The Ohio Country was the key to growth and prosperity. As Washington wrote to the governor of Virginia in 1784, I need not remark to you Sir, that the flanks and rear of the United States are possessed by other powers, and formidable ones too; nor how necessary it is to apply the cement of interest, to bind all parts of the Union together by indissoluble bonds. These indissoluble bonds were canals. Washington proposed in the same letter to let the courses and distances of it [the Ohio River] be taken to the mouth of the Muskingum, and up that river to the carrying place with Cayahoga [sic]; down the Cayahoga to Lake Erie... and with the Scioto also. So Washington not only envisioned the Ohio and Erie Canal, but the cities of Cleveland and Akron, as well.

Ohio became a state in 1803, but progress on canals was slow. A lottery was created to finance navigational improvements along the states rivers, but few tickets were sold. Then, the War of 1812 intervened. After the war, it appeared that funding for internal improvements might be forthcoming from the federal government, but Pres. James Madison vetoed the Bonus Bill of 1817. This veto meant that it would be up to the states to build such projects. Gov. DeWitt Clinton of New York accepted the challenge, spearheading construction of the 363-mile-long Erie Canal. Connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, Clintons Ditch was the crowning transportation achievement of its time.

Completed in 1825, New Yorks Erie Canal changed the landscape in Ohio. Now that a canal to the west was operating, a canal opening up the western interior was the next logical step. Ohio was one of Americas poorest states in 1822, but Gov. Ethan Allen Brown was able to get $6,000 authorized to initiate surveys and establish a canal commission. The final route was announced in May 1825. Ohios canal, from Lake Erie to the Ohio River, would run along the Cuyahoga, Tuscarawas, Muskingum, Licking, Little Walnut, and Scioto Valleys from Cleveland to Portsmouth. (A second canal, the Miami Canal, was the result of a political compromise. It would eventually be extended to Lake Erie by 1845.) The dizzying success of the Erie Canal in New York meant that material, men, and money would not present any barriers for the financially strapped state of Ohio to undertake its grand internal improvement project.

Governor Clinton himself turned the first shovelful of earth during ground-breaking ceremonies for the Ohio and Erie Canal near Newark on July 4, 1825. This act would be repeated millions of times, as mostly Irish immigrants poured into the Buckeye State to work from sunup to sundown for 30 a day and a jigger of whiskey under horrendous conditions. The new canals dimensions were nearly the same as those on the Erie Canal: minimums of 40 feet wide at water level and 26 feet wide at the bottom; a depth of 4 feet; and a 10-foot-wide towpath. Progress was steady, and, two years later, the first section of the Ohio and Erie Canal was completed, from Cleveland to Akron. Ohio governor Allen Trimble and canal commissioner Alfred Kelley were among dignitaries who traveled on the first boat, the State of Ohio. A wild celebration greeted the State of Ohio when it arrived in Cleveland on July 4, 1827, as everyone in the cheering crowd realized that the canal would allow them to sell high and buy cheap. In fact, export commodity prices more than tripled overnight.

Similar celebrations greeted the canal as it stretched southward to Massillon in August 1828, Dover in October 1829, Newark in July 1830, and Chillicothe in October 1831. When it finally opened to Portsmouth on October 15, 1832, the completed Ohio and Erie Canal was 309 miles long. It consisted of 14 aqueducts, 155 stone culverts, and 148 lift locks, used to overcome an elevation difference of 1,207 feet. These statistics were subject to change throughout the lifespan of the canal. For example, the number of aqueducts would almost double, to 27. Locks were 90 feet long by 15 feet wide. The cost to build the system, which included a network of feeder and sidecut canals and associated reservoirs, was $7,904,972.

Despite inherent disadvantages, such as a four-mile-per-hour speed limit and seasonal operation, the state-operated canal system was generally successful. Never particularly profitable due to high maintenance costs, the canals, within a generation, transformed Ohio from a backwoods frontier wilderness into the nations leading state in terms of agricultural output. Real estate values increased by an unbelievable 1,400 percent in Ohios 37 canal counties from 1826 to 1859, and the state became the nations third most populous. Receipts on the canals increased steadily, peaking at $799,025 in 1851. Then, the bottom dropped out. Receipts were down to $109,286 by 1861, and the state leased the system to private interests that same year. Railroads, something nobody could have predicted in the age of George Washington or DeWitt Clinton, were the cause. Rails advantages of speed, year-round operation, and low maintenance costs doomed the canal system.

Next page