Until I Say Good-Bye

My Year of Living With Joy

Susan Spencer-Wendel

with Bret Witter

For Stephanie

whom God divined my sister

Happy the Man

Happy the man, and happy he alone,

He who can call today his own:

He who, secure within, can say,

Tomorrow do thy worst, for I have lived today.

Be fair or foul or rain or shine

The joys I have possessed, in spite of fate, are mine.

Not Heaven itself upon the past has power,

But what has been, has been, and I have had my hour.

J OHN D RYDEN

Contents

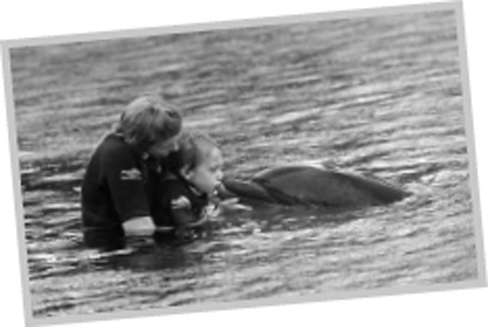

M y son Wesley wanted to swim with the dolphins. He was turning nine on the ninth day of the ninth monthSeptember 9, 2012and this was his special request.

I had promised each of my three children a trip during the summer, each to a destination of their choice. A time for togetherness. A time to plant memories to blossom in their futures.

A present for themand me.

In July, I traveled to New York City with Marina, my teenage daughter. In August, our family spent a week on Sanibel Island, off the west coast of Florida, at the request of my eleven-year-old son Aubrey.

The trips were part of a larger plan: a year I dedicated to living with joy. A year in which I took seven journeys with seven people central in my life. To the Yukon, Hungary, the Bahamas, Cyprus.

A year also of journeys inward: making scrapbooks from a lifetime of photographs, writing, creating a haven in my own backyarda Chickee hut with open sides, a palm frond roof, and comfy chairs where I summoned memories and friends.

Journeys I found more perfect in their doing than I had in their dreaming.

Wesleys trip was the simplest and the last. A three-hour drive in our minivan from our home in south Florida to Discovery Cove in Orlando.

What a beautiful drive, my sister Stephanie commented, cheerful as ever, as we passed through the swampy monotony of central Florida.

Discovery Cove featured a huge artificial lagoon. A beach ringed one side, with rocks on the others. Palm trees rose above the lush landscape. Their fronds looked to me like fireworks heralding the occasion there.

We gathered on the beach in a drizzle, watching fins slice through the play area on the other side of the lagoon.

Which one is ours? Wesley asked. Which one is ours?

A trainer led us into the water. Suddenly a creature appeared before us: a smooth gray face with shining black eyes, a long mouth with edges turned upward as if in a smile. Her bottle-nose bobbed, signaling I want to play!

Wesley was over the moon. He jabbered and jumped, too excited to stand still. With his long blond hair, wetsuit, and blue eyes, he looked like the surfer boys I so admired in my youth.

Happy Birthday, my son.

Aubrey and Marina stood beside him, just as delighted.

Isnt it mean to keep them penned up? Marina asked no one in particular. Then the dolphin surfaced near her, and she made fun of her blowhole. Marina was near fifteen years old, her thoughts a jumble of the juvenile and the adult.

The trainer introduced us. Her name was Cindythe dolphin, not the trainer. Cindy swam by slowly, allowing us to run our hands down her body. I was stunned by her size: eight and a half feet long, five hundred pounds of stone-solid muscle.

What does she feel like? the trainer asked.

A Coach purse, wisecracked hubby John.

I love Cindy! Wesley gushed.

Cindy was more than forty years old. I asked if she had children.

No, Cindys a career woman, said the trainer.

Like me, a lifelong journalist. But I had children. I had the pleasure of standing with them in waist-deep water and feeling the skin of an aquatic wonder.

The trainer asked us to lift our hands to signal Cindy. Make a motion like you are reeling in a fishing line, and Cindy makes a sound just like it.

Wesleys mouth dropped open in amazement. I love Cindy! he said.

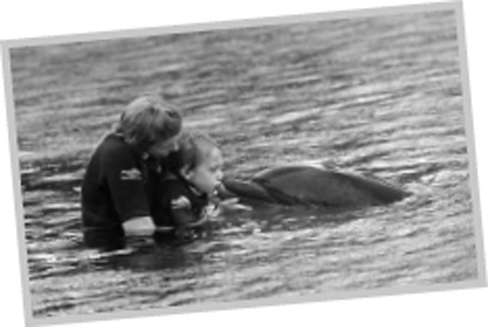

With the trainers help, Wes grabbed her dorsal fin. He laid his body flat along her back, and for the next half hour Cindy pulled us one by one through the water. First the children, then Stephanie and John.

When it was my turn, I declined. Let Wesley take my ride, I said. For this day was his day. The wonder on his face was obvious as Cindy skimmed him through the water.

We took many photos that day. Of Wesley. Of Aubrey and Marina. Of our family, smiling together on the beach in the rain.

There is one I adore: John holding me half out of the water, so that I might kiss Cindy on her smiling snout.

At the moment, I thought only of the gentle giant in front of me, of the smooth cool of her bottle-nose as I kissed it. A memory made.

When I saw the photo, I thought of the gentle giant behind me, lifting me as he does every day. I thought of my children, whose happiness enriches me. Of my sister and friends, who make me laugh.

I thought of Wesley, whose ninth birthday is likely the last I will share.

I cannot walk. I was rolled to the lagoon in a wheelchair.

I cannot support my own weight, even in water. John carried me from the chair and held me so I would not drown.

I cannot lift my arms to feed myself or hug my children. My muscles are dying, and they cannot return. I will never again be able to move my tongue enough to clearly say, I love you.

Swiftly, surely, I am dying.

But I am alive today.

When I saw the photograph of myself kissing the dolphin, I did not cry. I was not bitter for what I had lost. I smiled instead, living the joy.

Then turned in my wheelchair, as best I could, and kissed John too.

I ts odd to think of my autopilot life, the one before.

Forty-plus hours a week working a job I loved, writing about the local criminal courts for the Palm Beach Post . Another forty navigating the daily dance of sibling warfare, homework, and appointmentspediatrician, dentist, orthodontist, psychiatrist (no surprise, eh?).

Hours at music lessons with my childrenor driving between them.

Evenings spent folding laundry on our dining room table.

An occasional dinner with friends or my sister Stephanie, who lived down the street.

A quiet float in the backyard pool with my husband, a few minutes at the end of the day, interrupted by a kiddie disagreement over television channels or six-year-old Wesleys out-of-nowhere request to draw on our spoons.

Okay. On the white plastic ones. Not the silver ones!

I felt lucky.

I felt happy.

And like anyone, I expected that happiness would sail on and onthrough proms and graduations, weddings and grandchildren, retirement and a few decades of slow decline.

Then one night in the summer of 2009, while undressing for bed, I looked down at my left hand.

Holy shit, I yelped.

I turned to my husband John. Look at this.

I held up my left hand. It was scrawny and pale. In the palm, I could see the lines of tendons and the knobs of bones.

I held up my right hand. It was normal.