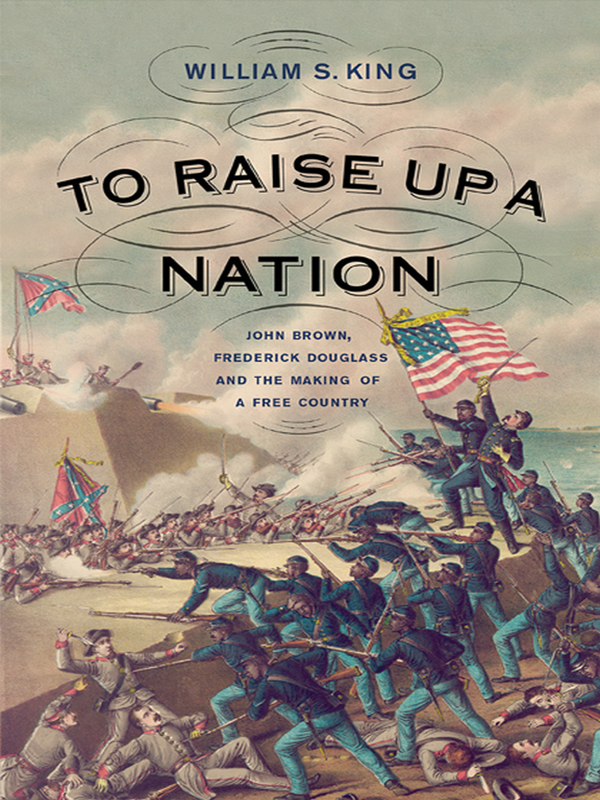

William S. King - To Raise Up a Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and the Making of a Free Country

Here you can read online William S. King - To Raise Up a Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and the Making of a Free Country full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Westholme Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:To Raise Up a Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and the Making of a Free Country

- Author:

- Publisher:Westholme Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

To Raise Up a Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and the Making of a Free Country: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "To Raise Up a Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and the Making of a Free Country" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In his fast-paced and deeply researched To Raise Up a Nation, William S. King narrates the coming of the Civil War, the war itself, and the emancipation process, through the intertwined lives of John Brown and Frederick Douglass. Kings stimulating, well-written account draws upon telling anecdotes and pen portraits to document Americas dramatic story from Harpers Ferry to Appomattox, a drama personified by the lives of Brown and Douglass.John David Smith, Charles H. Stone Distinguished Professor of American History, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and author of Lincoln and the U.S. Colored Troops

Drawing on decades of research, and demonstrating remarkable command of a great range of primary sources, William S. King has written an important history of African Americans own contributions and points of crossracial cooperation to end slavery in America. Beginning with the civil war along the border of Kansas and Missouri, the author traces the life of John Brown and the personal support for his ideas from elite New England businessmen, intellectuals such as Emerson and Thoreau, and African Americans, including his confidant, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman. Throughout, King links events that contributed to the growing antipathy in the North toward slavery and the Souths concerns for its future, including Nat Turners insurrection, the Amistad affair, the Fugitive Slave law, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the Dred Scott decision. The author also effectively describes the debate within the African American community as to whether the U.S. Constitution was colorblind or if emigration was the right course for the future of blacks in America.

Following Browns execution after the failed raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, King shows how Browns vision that only a clash of arms would eradicate slavery was set into motion after the election of Abraham Lincoln. Once the Civil War erupted on the heels of Browns raid, the author relates how black leaders, white legislators, and military officers vigorously discussed the use of black manpower for the Union effort as well as plans for the liberation of the veritable Africa within the southern United States. Following the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863, recruitment of black soldiers increased and by wars end they made up nearly ten percent of the Union army, and contributed to many important victories.

To Raise Up a Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and the Making of a Free Country is a sweeping history that explains how the destruction of American slavery was not directed primarily from the counsels of local and national government and military men, but rather through the grassroots efforts of extraordinary men and women. As King notes, the Lincoln administration ultimately armed black Americans, as John Brown had attempted to do, and their role was a vital part in the defeat of slavery.

William S. King: author's other books

Who wrote To Raise Up a Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and the Making of a Free Country? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.