The Aha! Moment

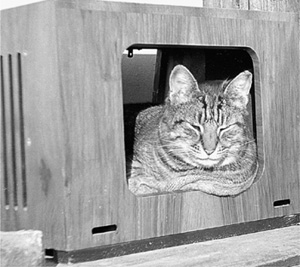

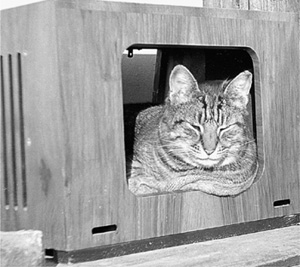

Creature Jones in His Telly

This domestic cat invented a joke and had an idea. A creative animal!

The Aha! Moment

A Scientists Take on Creativity

David Jones

2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2012

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jones, David E. H.

The aha! moment : a scientists take on creativity / David Jones.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-0330-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-4214-0330-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-0331-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-4214-0331-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Creative ability in science. 2. CreativityMiscellanea. 3. ScientistsPsychology. I. Title.

Q172.5.C74J66 2011

509.2dc22 2011010029

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

Tell me where is fancy bred, Or in the heart or in the head?

How begot, how nourishd? Reply, reply!

William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, act 3, scene 2, line 63

Contents

Preface Creativity in My Career

Having ideas! This book is a report from the front. I am a scientist, and I tell many scientific stories; but my notions of creativity include practitioners of the artswriters, poets, composers, and other celebrated creators. I was also the crazy scientist Daedalus in New Scientist, and then in Nature and in the Guardian newspaper. An ideal Daedalus column started with something everyone knew and finished with something nobody could believe. Where had the argument gone wrong? Daedalus became one of the longest-running jokes in scienceI wrote nearly nineteen hundred weekly columns.

In parallel with this crazy output, I did proper scientific research. My publications include serious scientific papers, as well as two books expanding and illustrating Daedalian schemes. Some of these actually came true; indeed, you cannot judge in advance whether a new idea will work out, though few of them do. Thus one Daedalian idea won a Nobel Prize for the people who finally made it work, and another was incorporated into President Ronald Reagans proposed Star Wars project, which was a factor in ending the Cold War.

Another career I got into was making objects and experiments for TV and for science museums. Together with the Daedalus column, this steady novel practicality made me ceaselessly creative. I evolved a theory of creativity, based on my own challenges and successes. There may be other ways, but this is mine. I expound on it in give examples of my public projects, some of the problems I encountered, and some of the feelings I had while trying out my experiments.

Creativity can often surprise its owner. At its best, a wild aha! moment suddenly gives you a new idea. I reckon it comes from a creative part of the unconscious mind, which I call the Random-Ideas Generator, or RIG (I think of it by its initials, because creativity certainly cannot be rigged, as this book will show!). Jokes and new ideas seem to use the same area of the mind; so my Daedalian jokinesswhich also flows in this bookhelped my creativity. You cant make contact with the RIG, or at least I never made contact with mine. And, most of its ideas are wrong. All creative people have to live with lots of failure. Worse, coming up with an idea is only a tiny part of the whole creative process. It may take years of hard work to get an RIG idea into practice.

Theres a special feel to being creative. Creativity is the essential cutting edge. But ultimately, your work has to form a product of some kind. For a writer or an artist, the result has to be printed, exhibited, or otherwise put before a public. A museum curator or TV producer knows that his ideas must go in front of an audience of one sort or another. And a research scientist knows that his results will appear as a scientific paper in an academic journal. Scientific papers are detailed, formaland boring. In , I describe some of mineand reveal the exciting emotions that always drive research, though papers never hint at them.

The last section of the book looks around a bit. Chapter 13 discusses some of my private creative projects, and tells of my life-long accumulation of facts and notions, which I now feel aided my creativity. That chapter also spells out my fascination with literary styles. Chapter 15 is a challenge to creative inventors: it recounts some inventions we need. Chapter 16 airs some of my current (quite possibly silly) questionsalways a valuable stimulus to creativity. Chapter 17 condenses some of my advice on being creative.

THAT MIXED-UP CAREER OF MINE , part media freak and part serious scientist, has sparked this book. Daedalus might be deliberately silly, but my serious science often failed too. And my wild media-freakery often helped my serious science, prompting, for example, my discovery of arsenic in Napoleons wallpaper (see ).

I tell lots of stories. They are not in any textbook; indeed, I dispute many textbook claims. Daedalus has leaked into many of the stories, as he also leaked into real life. I often stick my neck out and risk its being chopped off.

!)

My poor parents showed great heroism. They put up with my highly deviant and often destructive behavior. So did the neighbors, who often had to respond to pleas of can I have my rocket back? All my projects ran in parallel with the complex science curriculum of Eltham College. I went to Imperial College in London, and David to (the then) Woolwich Polytechnic. We both got bachelors degrees in chemistry and stayed on in our institutions to get Ph.D.s, also in chemistry. Later I did postdoctoral chemical research at Imperial College.

Daedalus was born from a chance meeting with Edward Wheeler (). Edward had studied physics at Imperial College with me, and I wrote much of the college magazine with him. One key editor was the famous Nazi sympathizer David Irving (he had those leanings even back then).

After a year of teaching at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, I joined the Imperial Chemical Industries Corporate Laboratory in Run-corn in northwestern England. They probably accepted me because as Daedalus of New Scientist, I published a crazy idea every week. (I made a special publishing deal with their patents people.) None of my industrial schemes were actualized; though I developed my theory of bicycle stability at Imperial Chemistry Industries (ICI, ).

In 1973 I left ICI and went to the University of Newcastle upon Tyne as a research fellow in the chemistry department. While there I attracted the attention of Yorkshire Television Ltd., or YTV. Soon I became their chief physical science consultant. I started to make things for them to put in front of their national audience and their cameras.

Next page