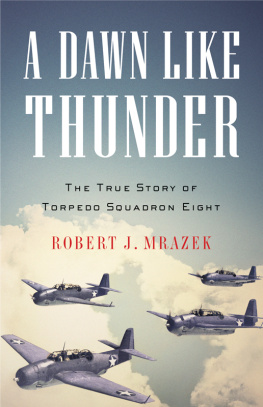

Copyright 2008 by Robert J. Mrazek

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site atwww.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: December 2008

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-316-04098-3

Book design by Fearn Cutler de Vicq

Maps by Julie Krick

Also by Robert J. Mrazek

The Deadly Embrace

Unholy Fire

Stonewalls Gold

For my son,

1st Lieutenant James Nicholas Mrazek, U.S. Army,

1st Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment,

Forward Operating Base-ISKAN, Iskandariah, Iraq

(20062007)

They did their share.

An the dawn comes up like thunder...

Rudyard Kipling

Many men who never received mention

gave everything they had theyre still out there.

Gregory Boyington (USMC)

Below the sea of clouds lies eternity.

Antoine de Saint-Exupry

Ensign William Robinson Evans Jr., age 23

Pilot, Torpedo Squadron Eight

Norfolk, Virginia

December 7, 1941

My dear family,

What a day the incredulousness of it all still gives each new announcement of the Pearl Harbor attack the unreality of a fairy tale. How can they have been so mad? Though I suppose we have all known it would come sometime, there was always that inner small voice whispering no, we are too big, too rich, too powerful, this war is for some poor fools somewhere else. It will never touch us here. And then this noon that world fell apart.

Today has been feverish, not with the excitement of emotional crowds cheering and bands playing, but with the quiet conviction and determination of serious men settling down to the business of war. Everywhere little groups of officers listening to the radio, men hurrying in from liberty, quickly changing clothes, and reporting to battle stations. Scarcely an officer seemed to know why we were at war and it seemed to me there is a certain sadness for that reason. If the reports Ive heard today are true, the Japanese have performed the impossible, have carried out one of the most daring and successful raids in all history. They knew the setup perfectly got there on the one fatal day Sunday officers and men away for the weekend or recovering from Saturday night. The whole thing was brilliant. People will not realize, I fear, for some time how serious this matter is, the indifference of labor and capital to our danger is an infectious virus and the public has come to think contemptuously of Japan. And that I fear is a fatal mistake. Today has given evidence of that. This war will be more difficult than any war this country has ever fought.

Tonight I put away all my civilian clothes. I fear the moths will find them good fare in the years to come. There is such a finality to wearing a uniform all the time. It is the one thing I fear the loss of my individualism in a world of uniforms. But kings and puppets alike are being moved now by the master destiny.

It is growing late and tomorrow will undoubtedly be a busy day. Once more the whole world is afire in the period approaching Christmas it seems bitterly ironic to mouth again the timeworn phrases concerning peace on earth goodwill to men, with so many millions hard at work figuring out ways to reduce other millions to slavery or death. I find it hard to see the inherent difference between man and the rest of the animal kingdom. Faith lost all is lost. Let us hope tonight that people, all people throughout this great country, have the faith to once again sacrifice for the things we hold essential to life and happiness. Let us defend these principles to the last ounce of blood but then above all retain reason enough to have charity for all and malice toward none. If the world ever goes through this again mankind is doomed. This time it has to be a better world.

All my love,

Bill

F ollowing its devastating attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Empire embarked on one of the most stunning military campaigns in world history, conquering the American-held Philippines, the mighty British fortress of Singapore, Java, Malaya, the oil-rich Dutch East Indies, Sumatra, Hong Kong, Guam, and Wake Island. In the process, they virtually annihilated the Far Eastern fleets of Great Britain, the United States, Australia, and the Netherlands.

In less than six months, the Japanese killed or captured more than five hundred thousand Allied soldiers, and came to control the destiny of one hundred fifty million new subjects. They had conquered an empire that it took the Western colonial powers almost four centuries to acquire.

Along the Pacific coast of the United States, panic-stricken Americans feared an imminent invasion. In February 1942, President Roosevelt ordered 112,000 Japanese-Americans to be rounded up and sent to detention camps. It was a time of apprehension and alarm. For most Americans, the outcome of the war was in genuine doubt.

In early May 1942, American code breakers deduced from intercepted radio messages that the Japanese Imperial Navy was planning to eliminate the U.S. presence in the Central Pacific by drawing American forces into a final and decisive battle. Their target was Midway Atoll, consisting of two islands and an airfield lying twelve hundred miles west of Hawaii. Gambling that his code breakers were right, Admiral Chester Nimitz, the commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, committed his available forces to setting up an ambush.

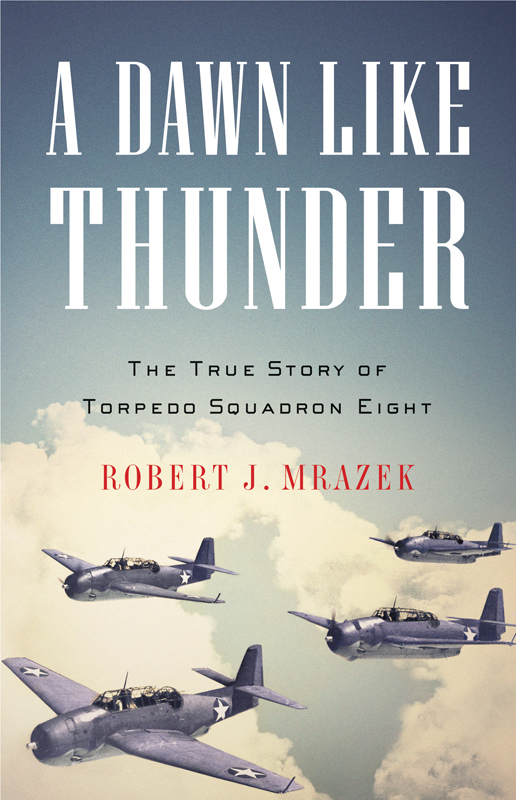

Midway has been called the most important naval battle ever fought between two great powers. The Japanese thought it would be a walkover, or in the words of one senior Japanese officer, as easy as twisting a babys arm. After everything their navy had accomplished up to that point, there was little reason to doubt his words.

The Japanese Empire was at the pinnacle of its glory. Having destroyed the last vestiges of European colonial power in the western Pacific, their confidence in their commanders, warships, combat aircraft, and each other was boundless. Many had come to believe that they were racially superior to the mongrelized and decadent Americans.

Against the five Japanese battleships, eight aircraft carriers, fourteen cruisers, fifty-five destroyers, and dozens of auxiliary ships now heading toward Midway, Admiral Nimitz had a combined force of three carriers, eight cruisers, and thirteen destroyers. Twenty-four ships against one hundred sixty-two.

Only two of his carriers, the Hornet and the Enterprise, were prepared for battle. His third carrier, the USS Yorktown, had absorbed a five-hundred-pound bomb hit in the Battle of the Coral Sea. Informed that the ship would require at least a month to be made seaworthy, Nimitz gave his repair division seventy-two hours to accomplish the task.

In spite of these fearful odds, on June 4, 1942, the Americans chose to confront the Imperial Navy at Midway. In assessing the battles importance, former defense secretary James Schlesinger wrote that it was far more than the turning of the tide in the Pacific War. In a strategic sense, it was a turning point in world history.

Just two months later, the second pivotal battle of the Pacific War was fought on the island of Guadalcanal. Guadalcanal was the land-based strategic equivalent of Midway, a savage and bloody campaign that determined the outcome of Japanese aspirations to secure control of its vast new Pacific empire.