Table of Contents

For Carolyn Rae, always

Out there, weve walked quite friendly up to Death;

Sat down and eaten with him, cool and bland ...

Oh, Death was never an enemy of ours!

We laughed at him, we leagued with him, old chum.

Wilfred Owen

Apparently the Gods were with us.

Otherwise we would have been blown to Kingdom Come.

Second Lieutenant Vern Moncur B-17 Pilot, Wallaroo

This is the story of an aerial bombing mission to Stuttgart, Germany, that resulted in a shattering defeat of the U.S. Army Air Forces in the Second World War. It is told through the eyes of some of the men who fought in the battle.

It was not lost through want of courage.

PRELUDE

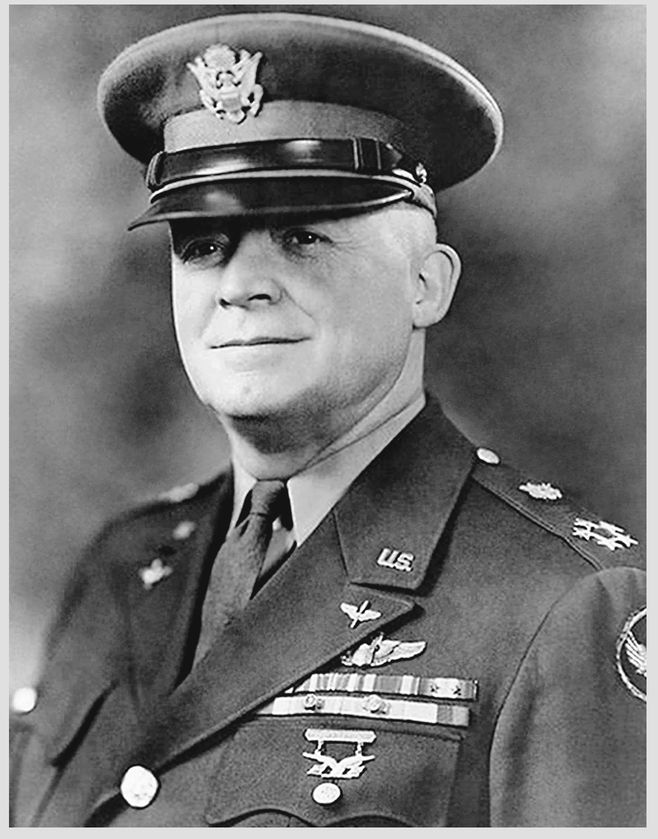

Hap

Tuesday, 31 August 1943

Fort Myer

Quarters Number 8

Arlington, Virginia

0530

General Henry Hap Arnold awoke in darkness. It had become his habit to rise before dawn since the war began. By the time his aide Clair Pete Peterson arrived at the house to take his baggage to the airfield, he had bathed, shaved, and was dressed in full uniform.

It was the fourth year of the most horrific slaughter in human history. Across the globe, more than 20 million people had died in the titanic struggle to defeat the Axis powers of Japan and Germany.

For the past eighteen months, Hap Arnold had lived on Fort Myers Generals Row, a few doors from George Marshall, the U.S. Armys chief of staff. Marshall had wanted all his senior officers to be quartered in the same protected military reservation. As the commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Forces, Arnold now led an organization of more than 2 million men equipped with fifty thousand aircraft.

The large brick house overlooked the Potomac River and enjoyed a magnificent view of the Capitol. Its spacious rooms were quiet since his wife, Eleanor Bee Arnold, had left him. On the few occasions they were together in the months before she moved out, she was always brimming over with complaints. Long ago, they had shared a deep romantic bond, celebrating the date of their anniversary every month. She remained proud of her husbands accomplishments, but had become increasingly bitter about his failure to make time for her. He understood it and regretted it.

The morning had dawned hot and humid, the kind of Washington tropical heat that sucked the energy out of a man, especially one who was still recovering from his second major heart attack in four months.

The first coronary occurred following an exhausting trip back from the Casablanca meetings in February 1943, after a series of tension-filled conferences with Roosevelt and Churchill over the future of his air force.

In the wake of the attack, he refused to allow a doctor to examine him, much less go to the hospital, out of fear of losing his job. According to army regulations, no senior officer could continue to serve on active duty if he had a serious illness. Only President Roosevelt had the authority to overrule the decision, and he had done so in Arnolds case. The general was considered too important to the war effort.

He was fifty-seven years old.

On this last morning in August 1943, he would leave behind the sweltering heat of Washington, as well as all the political infighting among the American war chiefs, to make an inspection tour of the Eighth Air Force command in England. The first stop on his transatlantic flight was Gander, Newfoundland, where it would be thirty degrees cooler than the U.S. capital.

Arnolds doctors had strongly urged him to cancel the trip. After his second coronary in May while attending the Trident meetings in Washington, he was still experiencing shortness of breath, his stomach ulcers were back, and his weight had ballooned, the product of too many old-fashioneds and rich desserts. At five feet eleven inches, he was still stocky and broad-shouldered, but no longer the trim 185 pounds he had been at West Point.

At the Point, he had earned the nickname Happy, later shortened to Hap, because of his seemingly perpetual grin. The grin was no more than a hereditary facial characteristic that belied his intense and often melancholy nature.

Much of the intensity stemmed from an austere childhood. His father, Herbert Arnold, had been a humorless Baptist doctor firmly set on his personal path to salvation. A rigid disciplinarian, he had raised his five children under the ascetic principle of all toil and no play. Young Henry had been put to work for a neighboring farmer at the age of seven. He hadnt stopped working since.

At 0820, General Arnolds command car arrived in front of Quarters Number 8 to take him to the airfield at Gravelly Point, a few miles down the Potomac River. His transport aircraft was waiting for him on the tarmac.

It was a four-engine Douglas C-54 Skymaster, and had been outfitted for a generals comfort. The plane carried twenty-six passengers in plush leather seats that were positioned in group settings. It was equipped with a full galley, as well as comfortable sleeping compartments for long ocean crossings. The president had one almost exactly like it. With a cruising speed of 200 miles per hour and a range of four thousand miles, it was perfect for the globe-trotting Arnold.

Four army generals and several other staff officers were traveling in Arnolds party that morning, including David Grant, the army air forces chief surgeon, and Arnolds personal doctor.

Arnold and the other passengers were given a briefing in lifeboat drill before the pilot took off from Gravelly Point at precisely 0900. Off to their left, the white dome of the Capitol shimmered in the steamy haze as they headed north along the Eastern Seaboard. Eight hours and sixteen hundred miles later, they landed at Gander, Newfoundland. It was raining and cold, with low clouds and light fog.

Most of the buildings at the airfield were newly constructed corrugated steel Quonset huts, surrounded by vast stores of supplies and equipment set out haphazardly in mountainous piles as far as the eye could see. Small caravans of fuel trucks moved slowly around the base like weary caterpillars. The airfields runways, aprons, and revetments were jammed with aircraft, including B-24 Liberators, Douglas B-18 Bolos, British Hurricane fighters, and transport planes of every hue and vintage.

Waiting to take off when Arnold arrived were several squadrons of B-17 Flying Fortresses on their way to join the Eighth Air Force as replacement aircraft. Arnolds C-54 would be following one of the squadrons across the North Atlantic later that night.

After an inspection tour of the military base, Arnold was scheduled to confer with Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill, the Royal Air Forces commander in chief of the ferry command, to discuss safer routes for his B-17 bomber crews on their flights from the United States to England. Bowhill was flying to Gander especially to meet him.

While the Skymaster was being refueled, Arnold embarked on his tour with the local army commander, periodically making notes in his confidential diary as they visited each installation on the post. The tone of his observations quickly became mocking.